The Menendez Murders misses the mark by using trauma as a mere plot point

While it may run contrary to the label, the success of any true crime show hinges on how it digs into the psychology of its main characters. The crime itself is only a secondary thought, a necessary bit of plotting that paces the insights into character. With most true crime narratives we know what’s going to happen simply because we’re already aware of the real-life facts of the investigation and trial. The Menendez Murders is in an even trickier spot; not only do many of us already know the real-life details of the crime, but the show itself laid nearly everything out in its series premiere. We know Lyle and Erik Menendez killed their parents. Their confession is a central part of the case. That means that The Menendez Murders, more than most other true crime shows, has even more work to do in order to be compelling from week to week.

The show has been struggling to find its footing since the very first episode, and last week’s third instalment was the most obvious example of The Menendez Murders failing to locate necessary dramatic tension. “Episode 3" built to a revelation of sexual abuse, as Erik finally admitted that his father abused him for years on end, but it was a climax that felt hollow. The lack of character definition for both Menendez brothers resulted in that deflating feeling. The reveal itself isn’t all that shocking, so it needs to be accompanied by an exploration of how it affects the brothers, the family, Leslie’s case, or the media coverage of the trial. Again, the “mystery” of the crime is only the surface intrigue; success comes from peeling back the layers and poking at what’s inside of these people.

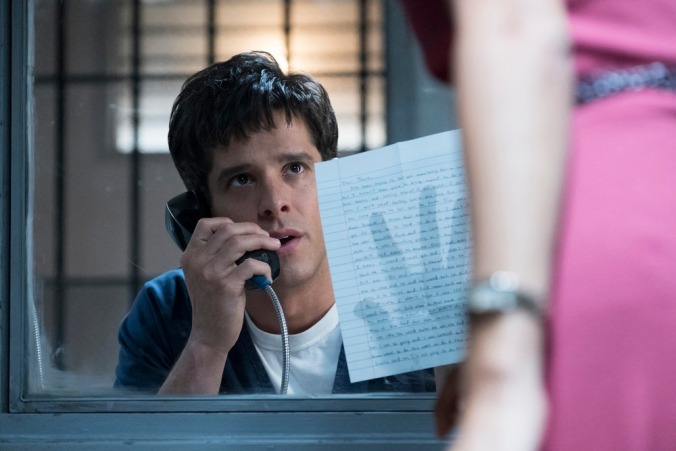

That’s where “Episode 4" comes in. It’s an episode that sets out to explain the repercussions of Erik’s testimony while also digging even deeper into the secrets hiding within the Menendez family. It’s an episode structured around last week’s reveal, as Leslie Abramson seeks to not only confirm Erik’s accusations of abuse, but also determine if Lyle was abused as well. Over and over again she tells her team that there’s more to this story, that they’re missing key pieces that will help the jury see the whole picture. By episode’s end she has what she believes is a solid defense of Lyle and Erik, pleading imperfect self-defense, which basically means that the brothers honestly believed their life was in danger, even if such a claim may seem unreasonable.

Sexual abuse is a difficult subject to talk about, both for a show that hinges on talking about it and a review that needs to pick apart what does and doesn’t work about the story. With that said, “Episode 4" feels like an exploitative hour of television, using sexual abuse as merely a storytelling device and not some sort of more meaningful peak into power dynamics and the trauma of victims. I was hesitant about the show’s reveal of Erik’s abuse last week, but figured there was still plenty of opportunity for The Menendez Murders to use that information in a productive way.

“Episode 4" doesn’t really right the ship though. Instead, it doubles down on how shocking all of this is supposed to be while giving little time to actually exploring the effects of such horrific abuse. In this week’s episode, Lyle admits that his mother was also an abuser, calling him into her room and making him “do things he knew were wrong.” Before long though he’s being pushed to reveal more, as the psychiatrist states that he’s likely covering for his father, idealizing his mother as a more “acceptable” form of abuse.

When Lyle, at the end of the episode, admits that his father abused him as well, it’s a moment that should act as an insight into this family and specifically the psychology of Lyle and Erik, and the dynamic they had with their father. Instead, a quick cut takes us to a closing scene inside Leslie’s office. She hears Lyle’s testimony and then lays out her case for imperfect self-defense. Lyle and Erik’s confession is immediately filtered through Leslie, removing us from the pain, positioning their testimony as cold evidence rather than personal trauma.

That kind of depersonalization is hurting The Menendez Murders as a whole. There’s no real sense of who these people are and how this case affects them. Instead, we’re getting characters that barely rise above their outlines of lawyer, cop, victim, and suspect. Part of that is just the nature of the procedural, but this isn’t your typical Law & Order series, where stories are contained to a single episode. The Menendez Murders is trying to flesh out the details of this crime across eight episodes, and while there might be enough case material to get through, the show isn’t engaging in any meaningful exploration of character psychology. That leaves the season’s biggest moments and most horrific reveals feeling rather trivial, as the show fails to follow through on important conversations and thematic explorations, instead reducing trauma to mere plot points.

Stray observations

- Before getting to a few more thoughts, note that this will be the final episodic review of The Menendez Murders. Apparently there aren’t too many folks itching to read about this show, and honestly, I don’t blame them. I might check in with an essay when the season finale airs, so you can keep an eye out for that if you’ve been following along.

- Another instance of the show skirting any real talk about the effects of this abuse is the scene where Erik and Lyle tell their family about what their parents did. There’s no real sense of how they might deal with such knowledge. Instead, the scene simply sees the uncle vehemently deny the claim. It’s a hint of emotional coping in the form of denial, but then it’s on to another scene.

- There are apparently six secrets in the Menendez house. I’m really not sure if that’s going to play into the plot later on this season.

- There’s so much opportunity here for The Menendez Murders to explore the harmful effects of toxic masculinity. It’s the crux of this whole story, and yet there’s a near complete absence of that subtext.

- Abramson is worried that her case is going to be “all tell and no show,” which could double as an analysis of The Menendez Murders.