Steven Spielberg’s oversight and stamp of approval, as well as an array of creative talent like Tom Ruegger, Paul Rugg, Sherri Stoner, Andrea Romano, and Pete Hastings, ensured that bold, specific voices were allowed a freedom and looseness in the show’s animated sketches. The premise was relatively complex: Three “toons” created in the 1930s, who ostensibly came to life and wreaked havoc on the actual Warner Bros. set (as well as starred in nonsensical cartoons), are locked the Warner Bros.’ studio water tower. In 1993, they “escape.” And so the Warner siblings’ escapades are drawn into or around various stories, skits, and musical numbers, which include a large cast of animated secondaries.

The show’s influences are numerous. The designs of the siblings may have been based on 1930s-era cartoons, but the personalities were based on Ruegger’s own three sons. The characters of Pinky and the Brain were based on two people Ruegger worked with on Tiny Toon Adventures. Slappy Squirrel was based on a comment made about Sherri Stoner, the character’s creator, acting like a teenager well into old age, while still having keen insight on other cartoon characters and gags. Other characters and stories were often based on staff members’ children or experiences, and classic cartoons and movies. The creative team was given quite a bit of freedom, and had a budget to match its ambitions. Multiple studios were chosen to animate the skits (including TMS, Wang, Startoons, and AKOM), with a higher cel count than most cartoons at the time, and an approximate 30-piece orchestra to score it (the exact amount is in dispute).

Spielberg’s comment may have been tongue-in-cheek, but it also plays into the kind of criticisms that could be tossed at the show. For all its comedic freedoms, it also can be too esoteric and “entertainment insider-y,” with whole gags and skits requiring specific knowledge of actors, media, politics, or social behavior. Television and film has been producing deep, purposely self-aware material from the beginning, but Animaniacs’ philosophy could be aggressive, hyper-comic satire on almost every aspect of entertainment from throughout its history. Parodies and celebrity putdowns were one thing, but the show’s deep well of jokes even hit radio, social/cultural commentary, fan culture, and the production of the media itself.

Note: For the sake of clarity, the season/episode number matches how it’s listed on Hulu.

1. “Yakko’s World/Cookies For Einstein/Win Big” (season one, episode two)

The Warner siblings work best when they’re portrayed as genuine, hyperactive children whose youthful exuberance extends hilariously into cartoon magic; here, it looks and feels like Yakko one day came up with all these national, rhythmic connections and could not wait to perform them (fun fact: Rob Paulsen did the entire song in a single take!). This energy follows through to “Cookies For Einstein,” in which the Warners constantly interrupt the scientist to try and make him buy his cookies. It all ends with an oddly heartwarming moment where the Warners end up inspiring Einstein’s energy-mass formula. The final segment, “Win Big,” introduces Pinky and the Brain, arguably the show’s best, richest, most consistent segment. Brain’s blunt, sardonic brilliance contrasts hilariously with Pinky’s abject, wacky idiocy, but neither gets far on their own. Add to that their outlandish world-conquering plan, and you have the perfect recipe for sustainability. (The pair would net itself a spin-off, which debuted in prime time.)

2. “Hercule Yakko/Home On De-Nile/A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (season one, episode 25)

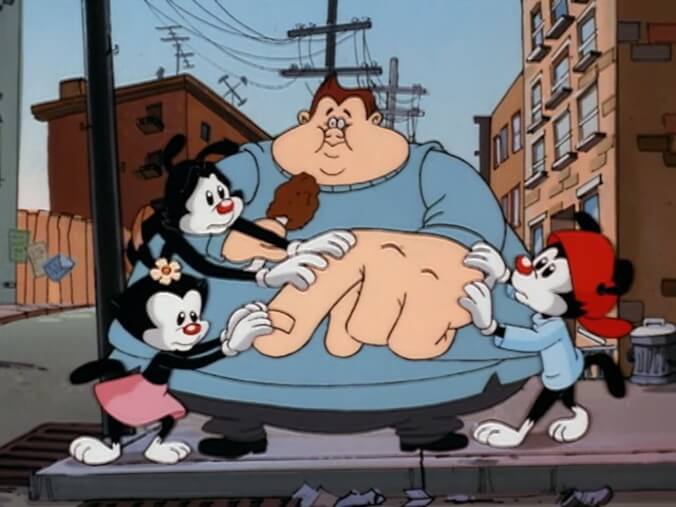

The episode that revealed that “fingerprints” could be the grossest double entendre ever, “Hercule Yakko” features a slew of secondary characters along with the main trio. They don’t really do much individually, but they do open the floodgates to mixing up the various characters in new, random ways, bringing life to weaker characters like the Hippos. The episode itself is plenty funny and ridiculous, even if it steps away from the “siblings as kids” concept and uses the “siblings as aggressive protagonists” formula instead. “Home On De-Nile” exposes the flaws in the pairing of Rita and Runt, Bernadette Peters’ musical theater chops notwithstanding. It was an experiment that didn’t last, as Animaniacs dropped Rita and Runt after the initial run. “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” is a funny, basic bit, with Dot “translating” Yakko’s reading of Shakespeare, and Wakko causing mischief in the background. It skirts the line between cute, cartoony, and self-aware, but once more, the animation elevates it all.

3. “Testimonials/Babblin’ Bijou/Potty Emergency/Sir Yaksalot” (season one, episode 26)

“Babblin’ Bijou/Potty Emergency/Sir Yaksalot” might be the closest that Animaniacs gets to some kind of thesis statement, capturing the essence of the Warner siblings and the humor they embody. Each skit is buttressed by short, odd testimonials of various classic 1950s actors and producers waxing nostalgic about the Warners and their encounters with Hollywood elites. It’s nonsense, but the commitment to the bit is great, with a running gag about how Yakko and Milton Berle hated each other; this never pays off, which is somehow even funnier. “Babblin’ Bijou” allows viewers to actually see what a Warner cartoon from the 1930s looked like, while “Potty Emergency” positions itself as a spiritual sequel of sorts to “Babblin’ Bijou,” with Wakko’s frantic desperation to find a place to potty escalating in incredible, hilarious ways and ending in just as weird and off-putting a manner (Wakko is the secret weapon of the show, which becomes more obvious later). “Sir Yaksalot” sneaks in some wonderful “artist” interference gags, similar to “Duck Amuck” (something the show hadn’t riffed on it up until this point), and brings in secondary characters to stick the ending, showing that mixing up the cast still yields dividends. Animaniacs’ meta-ness could sometimes be too much, but here it actually helps the segments cohere.

4. “Very Special Opening/In The Garden Of Mindy/No Place Like Homeless/Katie Ka-Boo/Baghdad Cafe” (season one, episode 35)

The occasional cameo in an Animaniacs cartoon can, and often does, pay off, letting more lackluster characters shine where they often struggled in their own milieu. In this season-one episode, Animaniacs pushes that idea to the limit, producing unique and often hilarious pairings. With the runner of the Warner siblings using various cartoony means to mix things up, we see duos like Mindy and the Brain, or Runt with Pesto from the Goodfeathers. Placing characters outside their comfort zones, so to speak, generates a new comic element while exposing the absurdity of each specific bit. Mindy’s mom and her complaints about Buttons become pointless nattering when directed at the Brain; Rita eats Pinky in a bit that lasts less than a minute. Slappy replaces Dot in a segment that sees the Warners unload their absurdity onto a Saddam Hussein caricature (an especially provocative bit), allowing the octogenarian rodent to question how Dot’s tics and catchphrases even work outside of the Warner sister’s characterization. It’s a clever way to showcase what does and doesn’t work within the cast, and where their potential truly lies.

5. “Critical Condition/The Three Muska-Warners” (season two, episode one)

Slappy Squirrel may be the trickiest character of the bunch, especially when viewed in hindsight. On paper, she’s an old cartoon squirrel who’s worked in the cartoon industry for so long that she knows darn near every comedy bit and every other cartoon character. In practice, however, she mostly executes genuinely funny gags but cynically comments on them at the same time, often ruining them. She knows they’re coming, we know they’re coming, she knows we know they’re coming. At their worst, these bits are not-so-clever observations about how good cartoon jokes work and more circle-jerking on being smarter than the jokes themselves. “Critical Condition” is the most excessive example: It pits Slappy against two Siskel and Ebert parodies, in an episode that doesn’t bother to be that observant. It mostly has Slappy blowing them up with explosives over and over again after the two critics give her old shorts bad reviews. It never quite snaps into place joke-wise; it’s just “hurt these mean ol’ critics,” and it falls flat. “The Three Muska-Warners” is a good comeback, if only because it commits wholeheartedly to a really dumb, classic joke and actually pulls away from any particular reference to the Alexandre Dumas story. It’s just a short bit of fun in a classic literary sandbox, something the show returned to time and again.

6. “Ups And Downs/The Brave Little Trailer/Yes, Always” (season two, episode 17)

Breaking the formula of an Animaniacs episode is somewhat unremarkable, as breaking formulas is intrinsic to the show. However, “Ups And Downs/The Brave Little Trailer/Yes, Always” pulls back from the show’s general tendency to stretch its meta-sketch energy, with three shorts outside its nebulous norm. “Ups and Downs” exposes the creative limits of the writers, but it’s also hilarious. Wakko really was the secret weapon of the Warners; he doesn’t indulge in winking self-awareness as much as his siblings, mostly responding to the energy around him in an id-like fashion. The episode’s Brave Little Toaster parody is an example of Animaniacs’ occasional one-offs, which were typically weak. This one’s a bit more charming, boosted by the animation from TMS. The third skit, with Pinky and the Brain, is an absolute banger, capturing how Animaniacs could thread the needle between obscure references and comical executions. The pre-internet world of the mid-’90s meant that only a select few would recognize it as a parody of an infamous Orson Welles breakdown, which only doubles the comic layers.

7. “The Warners 65th Anniversary Special” (season two, episode 30)

Continuity is not a central concern in a show like Animaniacs, but what main ideas it did have all coalesced into this send-up of awards shows and celebrations. If “Babblin’ Bijou/Potty Emergency/Sir Yaksalot” is Animaniacs’ thesis, then “The Warners 65th Anniversary Special” is its culmination, using a celebratory retrospective to tell a fake history of the siblings’ cartoons, complete with talking heads (from famous actors, producers, and actual Looney Tunes characters), reenactments, and “real” clips from fake classic black-and-white cartoons. It’s filled with great little touches. We see Weed Menlo, finally, who throughout the series is mentioned as the Warners’ first director, and learn how the Warners were created. We even get to see the weird yet warm relationship between the siblings and Dr. Scratchansniff, their unconventional father figure. “The Warners 65th Anniversary Special” blends all of the show’s best impulses (film history, well-executed slapstick, winking satire of award showcases) while avoiding its worst (the foray into real historical moments is handled with a light touch). Wakko steals the show, and even the requisite plot—a vengeful former co-star planning to blow up the Warners—doesn’t get in the way. Viewed as a season finale, “The Warners 65th Anniversary Special” is executed in fine form.

8. “A Hard Day’s Warner/Gimme A Break/Please Please Please Get A Life Foundation” (season three, episode four)

After the move to WB Kids, Animaniacs set its sights on network censors, contemporary shows about “nothing” (particularly Friends and Seinfeld), and the perceived emptiness of educational/earnest cartoons. It also went after its own fan base, whose obsession during the burgeoning days of the internet was ripe for (lazy) mockery. “A Hard Day’s Warner” has all the elements in one short, chaotic skit, with the siblings running from throngs of fans in a parody of A Hard Day’s Night, but it hits a bit deeper as the chase travels through a cartoon convention, digging at an obsessive fan base, a critical press, and censorship. “Gimme A Break” features a Slappy who’s been noticeably pulled back from her earlier incarnation, who now feels more like a “real” exhausted former cartoon star instead of a joke-for-joke’s-sake writers’ mouthpiece. And if “A Hard Day’s Warner” was too vague, “Please Please Please Get A Life Foundation” straight up ridicules the show’s most passionate admirers, placing them in an institution where they can be cured of their said obsession, mostly by hitting them with mallets. The slapstick is funny as always, but the target’s too easy. Animaniacs’ WB Kids output was still hilarious, but you can see the beginnings of base-level, Family Guy “describe the joke as you do the joke” bits, structured around “this person/show sucks” and “reference as gag” humor.

9. “Cutie And The Beast/Boo Happens/Noel” (season four, episode two)

By season four, Animaniacs had established three basic portrayals of the Warner siblings: young, clueless kids whose individual goals trigger a hyperactive cartoonish assault on anyone standing in their way; smarmy teens all too aware of their capabilities; and self-aware, slightly arrogant “toon actor” siblings who don’t really have stakes in the cartoon they’re acting in but do it anyway. Each portrayal has its pros and cons, and it usually depends on the writer and director whether or not it ultimately works. “Cutie And The Beast” mixes all three portrayals into something that also exemplifies the show’s strengths and weaknesses. Animaniacs’ imperative to foremost make viewers laugh is evident, but applied inconsistently and, at times, hypocritically. (It’s one thing to “hit back” at those forces that may arrogantly try to define what makes good comedy—Jerry Lewis is a prime target—but the bit also thinks of itself as the correct approach to how cartoons should work.) And if you squint during “Boo Happens” and “Noel,” you can see the very, very early nonsensical, absurdist comedy that would come to fruition in shows like Billy & Mandy, Flapjack, and even Teen Titans Go!

10. “Message In A Bottle/Back In Style/Bones In The Body” (season five, episode one)

Animaniacs’ zeal and relevance was really winding down in its final season. By 1997, the Warners lacked snap, and citing more contemporary shows did nothing to bolster the humor. But “Message In A Bottle/Back In Style/Bones In The Body” is a late-period highlight. “Message In A Bottle” is a simple cold opener. “Bones In The Body” tries to put a musical spin on the “Dem Bones” song, but is a throwaway skit, padded to kill time. “Back In Style” redeems the episode: Similar to “The Warners 65th Anniversary Special,” it sees the siblings loaned out to a variety of animation studios, letting the writers poke fun at the limited animated TV programs from the 1950s through the ’70s. The reach of the shows parodied is impressive. Sure, they do the obvious ones like Yogi Bear and Scooby-Doo, but they also get at Underdog, Pink Panther, and Fat Albert, while also showing caricatures of creators like Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones. The broad jokes toward that era of animation were nothing new in 1997, but the visuals and funky narratives were effective, and even the Warners themselves are unable throw off these classic animated worlds. The bit still dips into lazy humor at times (the Fat Albert kids talk very explicitly about how limited they are in animation), but overall, it stays on the right side of mean. The loan-out documentary format adds some historical winking cleverness as well. Even at this point, when the show had a target in its sights that it really grasped, it went all out.