10 years later, Graduation remains Kanye’s biggest, most joyful record

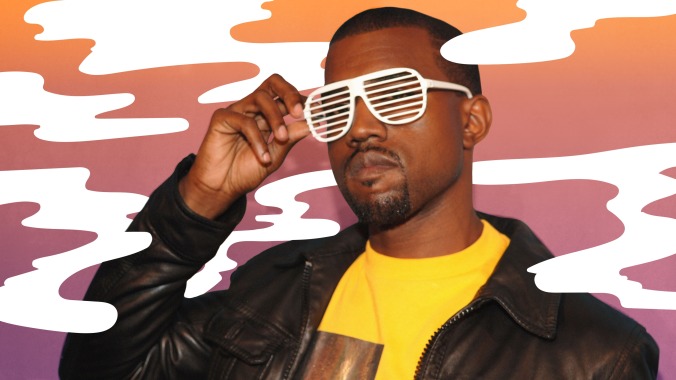

Kanye used to have this thing about being a bear, and you could tell everything you needed to know about him from it. On The College Dropout, it was a real guy—Kanye in a bear costume—slouching bored on the sidelines of a basketball game. He’s disaffected, but there’s something cool and puckish about it, a class clown destined for better things. On Late Registration, Kanye is no longer playing the bear, replaced by a cartoonish representation of one sneaking into the hallowed halls of some Oz-like pop utopia and casting a shadow so large it stretches off the bottom of the album cover. And then, finally, comes Graduation—now a superflat anime bear bursting with fuchsia fanfare out of the pillar-lined world of academia, up and off the CD case, eyes aglow with neon lights in the distance.

The bear story was the narrative Kanye wrote for himself across his first three albums, and it was one of relentless upward mobility. The definitive quality of these albums is their sense of joy, an unbridled optimism for the future of Kanye West, hip-hop, and the world itself. His first words on The College Dropout were, in response to a fake Bernie Mac on the intro, “Oh, yeah, I got the perfect song for the kids to sing,” after which he did in fact perform a perfect song for the kids to sing. In contemporary interviews, he’d casually temper expectations, admitting that he’s “not the best rapper” in keeping with the critical consensus at the time: better behind the boards than on the mic. His first major solo track, “Through The Wire,” is one defined by its limits, Kanye rapping through a wired-shut jaw with infectious, scrappy exuberance. On Late Registration, his verses are cleaner, but the music has dilated into a lush universe of Jon Brion pianos and flutes and fluttering Adam Levines, big-tent backpack hip-hop at a scale never before conceived. Graduation was the logical extension of that, the sci-fi iconography of its videos suggesting that he had moved on up, past the East Side and into a condo on the moon. The Dropout-to-Graduation arc was a metaphor for the way Kanye’s intellectualism, class consciousness, and Common guest spots worked like rocket fuel for his ambition.

A decade later, it’s easy to forget that, back then, it all felt like a little… much. Critics heard Graduation as an overreach, one lacking the sumptuousness of its predecessors. Months of pre-release hype pitted it against the latest by 50 Cent, then a radio-rap hegemon. 50 Cent claimed he’d retire if West outsold him, and when Graduation smashed Curtis, it felt like an epochal shift, a sea change that has since been deemed the death of gangsta rap. Maybe it was. Or maybe Kanye just put out better singles, aligning himself with trap upstarts like Young Jeezy and T.I. by bringing DJ Toomp onboard for “Can’t Tell Me Nothing” and riding a futuristic mega-hit like “Stronger” through the summer. (50 Cent, meanwhile, countered with “I Get Money,” which sounded way better on other rappers’ mixtapes, as well as “Straight To The Bank,” which was exactly the sort of throwback Dr. Dre shit nobody wanted in 2007.) When the albums finally dropped—a decade ago today—people snoozed through Curtis and gave Kanye the W, but they also groaned at Kanye’s ambition, the encyclopedic worldliness of previous efforts traded here for scale at all costs.

And make no mistake: Graduation is huge, full of power ballads and sing-alongs and beats big enough to move the nation of millions that Kanye sought dominion over. Just listen to something like “Champion,” which cuts Steely Dan into a Friday-night dance-floor coke rush, or the sweeping, triumphalist head-banger “The Glory.” Kanye had recently come off stints opening up for The Rolling Stones and U2, the latter of which proved particularly influential to an artist looking to make heartfelt pop music written in broad, universal strokes. The overwhelming specificity of his previous records—the knotty rhyme schemes packed full of references—here became neatly syncopated bars, the tongue twisters of Late Registration turning into shout-alongs like, “Let’s get lost tonight / You could be my black Kate Moss tonight” (from “Stronger”). Gone were the indie-rock name drops of yore, replaced by less fashionable but more popular acts like The Killers, Keane, and Coldplay. “There’s just serious songs, hooks, chords, and ideas,” West promised listeners prior to release. “No special effects or antics… and no fake Bernie Mac!”

For all his solipsism, Kanye’s greatest gift is his sense of curation and talent management, cobbling together a cohesive set of collaborators, guests, and influences for each project. Here, that meant only one guest rapper—a golden age Weezy verse—and a handful of outsourced choruses. And while the record filters in Chicago house, krautrock, and lots of European techno, it’s the classic rock influences that define it.

Lyrically, it’s the moment Kanye began to turn inward, rendering the story of himself as all-important—the quintessential delusion of rock stardom. Many of the songs were designed to be played live, with instructions to “wave your hands” recorded right into album closer “Big Brother.” He was graduating into pure stardom, like Springsteen on Born To Run, ditching two albums of wily invention in favor of laser-focused pop appeal. Both Graduation and Born To Run promise propulsion in their titles, not just for the albums themselves but for the artists who made them. Springsteen kept gunning for the horizon, with a few pitstops in seedy motels along the way, but Kanye immediately began a series of total reinventions, tracing a descent over the ensuing decade into decadence, narcissism, self-loathing, and molten, Old Testament fury.

This is partly why Graduation has aged so well: It marks the end of one part of the Kanye story, the last time he sounded happy rather than merely animated or manic. If you miss the old Kanye, you miss the bear Kanye. And he left us prematurely: Graduation was intended as the third entry in a tetralogy, to be concluded with an album called Good Ass Job, the expected endpoint of higher education.

There’s something haunting about listening to Graduation in 2017, knowing that just a few months following its release, Kanye’s mother, Donda West, would unexpectedly die due to complications from surgery. Or that, in the months after that, he’d break off his engagement with his longtime girlfriend. In 2008, he’d ditch rap for the Auto-Tuned myopia of 808s & Heartbreak before reemerging as a new, singularly lurid emcee in 2009 across a string of guest verses—all of which set the stage for “Power” and the douchebag supernova of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. His taste for depravity reached its apotheosis on Yeezus, on which he scornfully turned the progressivism of his youth into punchlines about fisting his wife. These personal reinventions represented wholesale shifts in the fabric of pop music, an artistic “hero’s journey” he undertook publicly.

It’s easy to attribute this artistic and emotional derailment to the death of his mom, a college professor who raised him and defined his political ideology. One of his earliest solo tracks is Late Registration’s ode “Hey Mama”; another, still unreleased and even more illustrative of their relationship, is called “Mama’s Boyfriend.” Whatever the cause, his disillusionment was timely. If you, too, were expecting a good-ass job in 2008, a year in which the overwhelming avarice of late capitalism’s 0.1 percent resulted in a great recession of devastating unemployability—well, you could sympathize.

The inward gaze begun on Graduation curdled, as did his faith in the progressive ideals of Chicago-style liberalism. The rest of hip-hop was celebrating a Hova-quoting Chicago South Sider assuming the highest office in the land, but Kanye and Obama somehow never jelled despite the eerie parallels between them. In 2009, Obama called him a “jackass” after the first Taylor Swift encounter; on “Power,” Kanye declared himself cast out of paradise, “the abomination of Obama’s nation.” They continued periodically exchanging words—even roping in each other’s wives—a weird beef that ran parallel to Kanye’s increasing disillusionment with the politics of his youth. Transgressive sex and unbridled consumption took the place of self-conscious musings about needing Jesus. His political disaffection reached its nadir in the most obvious—and horrible—manner imaginable, as he scowled alongside a grinning paragon of American decline in a golden lobby last year.

Because of the past decade, we tend to think of Kanye as erratic and unstable, his Trumpism just a natural offshoot of his narcissism. We thought the same thing each time he declared his intentions to run for president, first at the VMAs last year and then again after meeting with Trump. But it’s worth taking these claims seriously, especially given the sloganeering of his early albums. Like any politician, Kanye saw his personal story as a conduit for political change; he cannily embraced his contradictions and flaws, positioning them as fundamental to his virtues. And he was overwhelmingly hopeful about the future he could build for us, if only we’d show up at the arena. While Graduation’s triumphant first third is full of campaign anthems, its final third is the stump speech, in which the rapper’s biography and community commingle to create his singular person. There’s a full-song ode to JAY-Z, shout-outs to Chicago street signs, wry jokes about his trashy Grammys suit, a beat Common passed on alchemically transformed into a jam.

It had a place, too. On Graduation, Kanye was gathering everyone in, filling his stadium, championing his own faults and the faults of his listeners as part of some greater vision for hip-hop. He has since left that vision piecemeal for other rappers: Kendrick assumed his intellectual conscience, Drake his global stardom, JAY-Z his seat at the boardroom table, Chance his political ambitions. In 2007, Kanye wanted all of those jobs at once, and believed it was just an album away. It was an audacious hope, and one worth rooting for.