15 years later, Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11 remains essential American agitprop

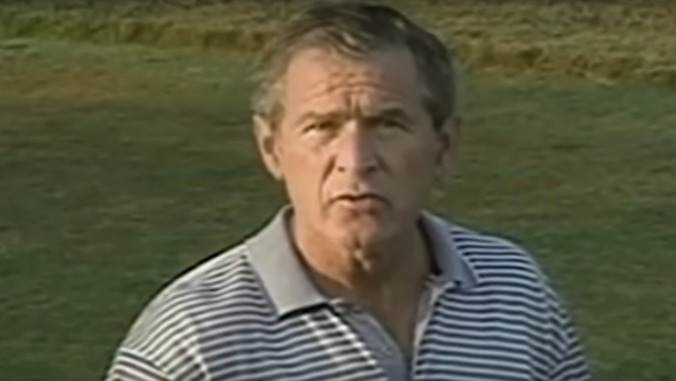

One of the most striking things about watching Fahrenheit 9/11 in 2019 is realizing just how deeply, uncomfortably resonant it is with our current state of the union. Within the first half hour, it depicts a venal, intellectually bankrupt administration led by a preening dimwit as he spends most of his time in the White House golfing and avoiding responsibility. And then—even more timely—the film depicts the American president actively impeding the cause of justice by trying to prevent the House Of Representatives or independent commissions from setting up probes to investigate the links between his own checkered past and avowed enemies of American democracy that might not-so-secretly hold a little too much sway over him. Sound familiar?

But even without the striking parallels to our current fiasco of an administration, Fahrenheit 9/11 remains a potent and stirring work, cinema with the ability to boil the blood and activate righteous indignation in the viewer. True, Moore’s reputation has diminished somewhat in recent years. (Turning in messy and uneven works like Capitalism: A Love Story and Where To Invade Next certainly didn’t help, especially in comparison to the laser-focused coherence of his best films, like Roger & Me or Sicko.) A lot of this has to do with his self-aggrandizing persona, a loudmouthed man-on-the-street type who seemingly never met a camera for which he couldn’t mug. But focusing heavily on Moore’s cult-of-personality bravado tends to overlook the fact that he remains one of the country’s best and most effective creators of documentary propaganda, a craftsman of the highest order when it comes to assembling weapons of political persuasion.

We tend to define propaganda as intentionally misleading, but it historically can simply mean “biased,” which Moore’s work undeniably is. To call it successful propaganda is simply to acknowledge his ability to achieve his intended goals of promoting a left-wing populist ideology. Whether you’re entertained or irked by his disingenuous everyday-schlub routine, his films gain a powerful clarity whenever he’s not face-first to the camera, employing his increasingly hoary “aren’t I a stinker?” brand of satire. They become, in the absence of that shtick, potent Molotov cocktails of carefully orchestrated narrative—collages of fact, inference, and provocation calculated to incite maximum outrage in their audiences.

And with the genuinely world-changing event of 9/11, and the attendant profit-minded malice of the Bush administration’s response, Moore found a topic large enough to accommodate his outsized sense of anger. “Was it all just a dream?,” the film begins, the director’s usual voiceover snark tempered by a tone of disbelief. The look back on the first four years of Bush’s presidency still resembles something out of farce: the history of a banana republic, an assessment whose bill the United States now all too clearly fits. A first cousin to the candidate, working in the employ of a right-wing media network, calls the election for his relative, and the media unquestioningly follows suit. A stolen election succeeded by an unjust war based on obvious lies gives Moore a clear throughline to follow, as he traces the crude manipulations of public fear in the “War On Terror” to the redacting of media imagery from the Iraq War to the ways our militarized culture preys on the poorest and most marginalized communities to supply fresh bodies for the frontlines of our atrocity exhibit of a foreign invasion. To this day, the fallout of that administration’s lies weakens our country’s standing in the eyes of the world.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.