With Wild At Heart, 1990 was a big year for David Lynch

Wild At Heart, the film Lynch brought to Cannes in the wake of Twin Peaks’ auspicious debut, feels beholden to little.

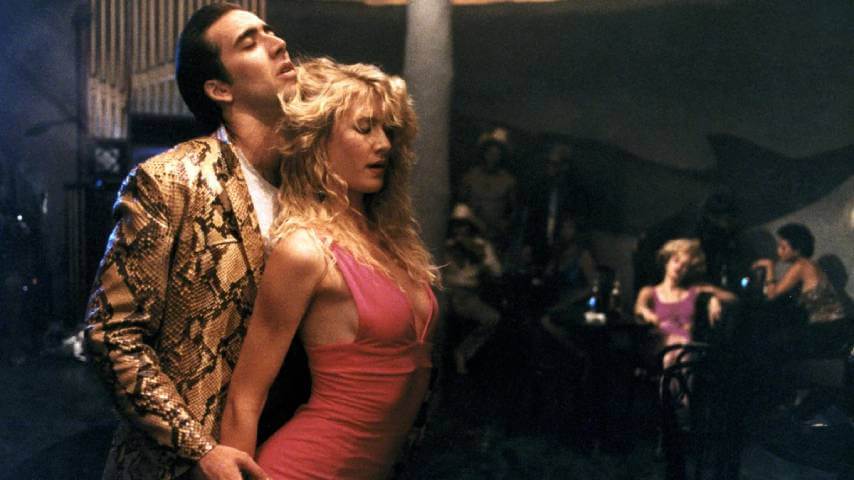

Photo: The Samuel Goldwyn Company

Wild At Heart (1990)

Call it a victory for the TV-is-the-new-cinema crowd or just proof that the small screen’s talent pool keeps expanding, but for the first time ever, television has earned an invitation to the Cannes Film Festival. Cannes, which began yesterday (and which yours truly is covering from the ground; read the kickoff dispatch here), will this year screen, however begrudgingly, the first couple episodes of two new TV shows, both by past Palme D’Or winners. I’ll probably skip Jane Campion’s Top Of The Lake sequel, China Girl—I admire Campion and quite liked the first season of her show, but I didn’t fly halfway around the world to get an early start on the fall TV season. What’s going to prove much harder to resist, however, is a first look at what could be the TV event of the year: the return of David Lynch’s groundbreaking whodunit whatsit soap opera Twin Peaks. New anything by Lynch is very rare these days. Also, it’s Twin friggin’ Peaks.

Exhibiting the revival of his prestige-TV milestone at the world’s most prestigious film festival must hold some special significance for Lynch. After all, the two things dovetail on his résumé, don’t they? Lynch first came to Cannes in May of 1990, flying with a print of his new movie, which he had completed mere hours earlier, pushed underneath the seat in front of him. This was a big year—nay, a big couple months—for America’s nightmare laureate. Just a few weeks earlier, his pilot for Twin Peaks had aired to much awe, befuddlement, and rapturous acclaim—no one had ever seen anything like it on TV, and the show was a bona fide sensation by the time Lynch made his inaugural appearance in competition at Cannes, with the batshit movie he basically shot concurrently with his batshit show, even borrowing cast members from the latter to appear in the former.

To this day, Twin Peaks remains one of the weirdest, most stylish, most idiosyncratic visions ever allowed on network television, maybe on TV in general. It exploded the possibilities of what the medium could be. All the same, it was still a TV show, beholden not just to the demands of episodic storytelling, but also to standards and practices. Wild At Heart, the film Lynch brought to Cannes in the wake of Twin Peaks’ auspicious debut, feels beholden to little. It shows no great interest in its own story, which is really just a hook on which Lynch can hang his obsessions, his hang-ups, his acid-retro attitude. And, certainly, there’s nothing safe-for-ABC about the film’s splashes of sex and violence: bodies writhing in bare ecstasy, heads bashed in and blown off. People walked out in droves at early screenings. The MPAA threatened an X. (Lynch, bending to the outrage of both a little, trimmed some carnage, but the difference between the version that played on the Croisette and the one that opened in American theaters three months later is marginal.)

At Cannes, the reaction was mixed, to put it mildly. For each person thrilled by the movie’s black-comic transgressions, there was someone else disgusted or irritated by its open-road freak show, its never-ending parade of degenerate oddballs and sardonic debauchery. When Bernardo Bertolucci, head of the competition jury, announced that he and his cohorts (Aleksei German, Mira Nair, Anjelica Huston, and Christopher Hampton among them) were handing the Palme D’Or to this mad movie, the boos drowned out the applause. Lynch, polite and brief at the podium, looked unfazed by the jeers. “I can’t believe what’s happening,” he said. “It’s a true dream come true.”

In its near-constant, laughing-gas lunacy, Wild At Heart is the closest Lynch has ever come to making a bona fide comedy. And in a filmography highlighted by eerie musical performances (the lip-sync showpiece of Blue Velvet, the mesmerizing Club Silencio scene in Mulholland Drive), it comes the closest to a hypothetical “David Lynch musical,” high on heavy metal and Chris Isaak, straight through to a breaking-into-song ending that puts that genre influence front and center. But Wild At Heart is also Lynch’s shrillest movie, his most garishly over-the-top, the one that threatens to twist his regular preoccupations—lost highways, the submerged horror of Americana, Elvis Presley—into a swaggering shtick. If a Lynch movie could ever be accused of self-parody, this would be the one.

The source material is a book, then unpublished, by Barry Gifford—the first in a series of road-noir novels he wrote about two horny star-crossed lovers, crisscrossing the American Southwest. Sailor, brought screaming (and boogieing and crooning) to life by Nicolas Cage at his most unrestrained, is the insane-asylum version of a ’50s greaser outlaw. Laura Dern, in what then counted as a deviation from a more squeaky-clean career path, plays Lula, his sex- and excitement-starved sweetheart. After a stint in prison for killing a man in something resembling self-defense, Sailor picks Lula up in his ostentatious ’50s convertible, and they head for California, breaking his parole in search of a more sensational life. But Lula’s mother, Marietta (Laura Dern’s actual mother, Diane Ladd), despises Sailor, in no small part because he rejected her advances. And so she sends a few unsavory customers (a private eye, a couple of assassins) to hunt the young lovers down.

To say that Lynch is more interested in the journey than the destination would be an understatement. With Wild At Heart, he takes every narrative off-ramp he spots, lets loose ends dangle, and perversely subverts even the promise of chase-movie danger. (That the bad guys never really catch up to the good guys could be a joke or just a shrug.) Sailor and Lula themselves disappear often into detours and memories, Lynch cutting over and over again to the image of a fiery trauma from Lula’s past (fire is a motif, sparked repeatedly by a lit match) or turning anecdotes into vignettes, like the one starring Crispin Glover as a mentally ill shut-in with a habit of stuffing cockroaches up his anus. It’s no great shock that more than an hour of deleted scenes exist for Wild At Heart. One could probably add or subtract digressions without much change to the cumulative effect.

Is there a life-sized performance in the movie? Just about everyone is a camp cartoon, beginning with Lynch’s wild-man star. Rocking a snakeskin jacket from his own wardrobe, Cage punches and kicks the air, thrusting his hips around like someone impersonating an Elvis impersonator, complete with sketch-comedy drawl. He’s cranked to 11 in that familiar way, but Wild At Heart is so overpopulated with weirdos that the actor has no foil to play his theatrics against; it’s the rare instance when Cage actually seems to be struggling to keep up with the craziness happening around him. Certainly, there are plenty who give him a run for his scenery-chewing money. Ladd, for example, plays all of her scenes at a fever pitch of boozy hysteria—howling with indignation, smearing her whole face in blood-red lipstick, summoning the vamping ghost of Hollywood divas past. That she earned an Oscar nomination for the performance is either an unholy miracle or proof that industry clout can buy anything.

If the film has an emotional center, it’s Dern. Lynch had cast her before, contrasting the actress’ schoolgirl innocence and vulnerability against the hideous, black-hearted menace of Blue Velvet. In Wild At Heart, she gets her own initiation into the midnight joyride club—Lula is no babe in the woods. Still, Dern finds a truth, a radiant sincerity, in her cross-country lovesick voyage. Like Naomi Watts in the audition scene of Mulholland Drive, she’s real, even if everything around her isn’t. Dern, in her three trips to Lynch Land, has put an enormous amount of trust in her director, following him into the darkest places. There’s an especially repulsive, cruel scene in Wild At Heart in which Willem Dafoe, sneering through his fake gums, seduces a pregnant, petrified Lula like a biblical serpent made sweaty flesh. It feels, in the context of this sick-joke funhouse, like an abuse of her commitment. (Lynch would up the ante of torment with what’s now looking like his cinematic swan song, Inland Empire—a movie that twists Dern’s visage into terrifying new shapes.)

Lynch may be the most diabolically gifted director of his generation; even his follies, like this and the spectacularly failed sci-fi blockbuster Dune, paralyze you with their mania. There are sublime moments in Wild At Heart, no question. One arrives early, as Sailor and Luna make the decision to hightail it west, but not before a night of celebratory dance. As Dern feverishly stomps the hotel room bed, Lynch match-cuts to the two cutting a mosh-pit rug to the machine-gun groove of forgotten speed metal group Powermad. After putting some young punk in his place, Sailor hijacks the show with a cover of The King’s “Love Me,” the band hilariously—and without a missed beat—providing dreamy accompaniment. It’s may be the funniest scene in Lynch’s filmography, but also a kind of jukebox mission statement, drawing a straight line of kindred rock ’n’ roll spirit from Elvis to thrash.

The film’s other highlight arrives later, when Sailor and Lula veer off road to investigate a car crash and find Sherilyn Fenn, from Twin Peaks, splattered in blood and stumbling around in a dying daze. While Lynch plays most of the violence in Wild At Heart for provocation (the opening brain bashing) or dark humor (a dog running off with a severed hand), this interlude carries an almost profound melancholy. It’s the one moment of terrible beauty he conjures.

Most of Lynch’s movies are dreams, by his own admission and virtue of their rabbit-hole logic. They come from somewhere deep in his subconscious, a place where the fantasias that inspire him breed, birthing new transmissions of wonder and dread. Wild At Heart is his nightmare pastiche of road movies, outlaw crime pictures, lovers-on-the-lam thrillers, small-town noirs, and (yes) old Elvis vehicles. Explicitly, Lynch is also riffing on The Wizard Of Oz; there’s talk of Toto, a yellow brick road, and red slippers, plus a cameo by Glinda The Good Witch and her wicked counterpoint. But little of this coheres into more than a random, arch smattering of references: Lynch’s own skip down the yellow brick road of movie history. The “Love Me Tender” happy ending that he insisted upon, deviating from Gifford’s template, isn’t especially cathartic, because Sailor and Lula are just warped archetypes, living out a love story with parentheses around it. Beyond Dern’s devoted performance and that crash-site pit stop, there’s nothing especially genuine in Wild At Heart. Even Eraserhead, for all its hellish sights and (especially) sounds, put something human at the core of its madness.

After Wild At Heart, Lynch became a semi-regular at Cannes. It’s where he premiered his uncharacteristically G-rated The Straight Story, as well as what many consider his masterpiece, the reconfigured pilot Mulholland Drive. It’s also where he chose to close the book on his short-lived TV phenomenon: The genuinely chilling Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me premiered just two years after Wild At Heart won the Palme and earned its own chorus of boos. Given that history, the festival probably didn’t need to qualify the inclusion of the new Twin Peaks this year; everyone understands that it’s Lynch’s name (and Campion’s) that earned TV an invite to film’s annual gala of esteem. In retrospect, one can’t help but wonder if Twin Peaks, as much as Wild At Heart, deserved to be there in 1990, too. It would take some serious cinematic partisanship, after all, to see less of his twisted genius in the primetime mystery of Laura Palmer than in the X-rated exploits of Sailor and Lula.

Did it deserve to win? Given the general glut of exciting competition titles at Cannes ’90, it’s not entirely surprising that Wild At Heart won: Nothing so consistently bananas is easily ignored. In fact, when held against the more measured art movies that Cannes tends to program, Lynch’s smorgasbord of dementia might have shaken the jury awake, like the thunderstrike of electric guitar that starts blaring in the opening scene, the film’s title landing on screen with the bombastic thud of an ’80s action movie. So, yeah, it makes sense. But I’d have pushed for White Hunter Black Heart. Clint Eastwood’s lightly fictionalized account of director John Huston, hunting elephants while location scouting for The African Queen, is one of the most mature films of the director’s pre-Unforgiven era—a filmmaker examining himself through another’s legacy.

Up next: After a more than 20-year drought, Italian cinema roars back into the Cannes winning circle with Nanni Moretti’s The Son’s Room.