20 years ago, But I’m A Cheerleader reclaimed camp for queer women

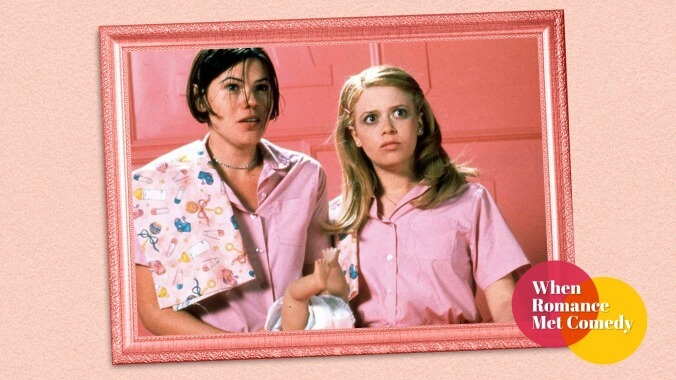

Image: Screenshot: But I’m A CheerleaderGraphic: Libby McGuire

“If I were writing a paper about it, I’d say it’s feminization of the camp aesthetic—bringing emotion to something that’s hyperrealized.” That’s director Jamie Babbit in an interview about her 2000 lesbian cult classic, But I’m A Cheerleader. The movie’s blend of high camp and rom-com earnestness made it a hit with audiences on the festival circuit but a source of frustration for critics, who felt that Babbit’s story of a high school cheerleader who falls in love at a gay conversion camp lacked the satirical edge it needed. “Some people say that I’m trying to be John Waters, but the film doesn’t have that bite,” Babbit explained. “But I don’t want it to have that bite… John Waters hates romantic comedies, he thinks they’re cheesy. But there’s a certain part of me that is cheesy. I’m a small town girl when it comes to relationships, and I wanted to tell a conventionally romantic story.”

There’s an element of reclamation to Babbit’s debut feature: “The history of camp has pretty much been defined by gay men, so I wanted to be sure that the film, while using camp, also had real emotional moments, that it was a romance.” As Roger Ebert presciently observed in his mostly positive review, “But I’m a Cheerleader is not a great, breakout comedy, but more the kind of movie that might eventually become a regular on the midnight cult circuit.” But I’m A Cheerleader has indeed spent the past 20 years as a beloved underground classic—a much-needed gem in an era where it was rare to find LGBT love stories that didn’t end in tragedy.

Most of But I’m A Cheerleader takes place at “True Directions,” a rancidly technicolor gay conversion camp. That’s where perky 17-year-old cheerleader Megan (Natasha Lyonne) is sent when her parents deduce that her vegetarianism and Melissa Etheridge poster (a.k.a. “gay iconography”) mean she has same-sex tendencies. While Megan initially rejects the idea on the grounds that she gets good grades, goes to church, and is a proud member of the cheerleading squad, she does have the habit of fantasizing about her female friends while unhappily making out with her boyfriend. So Megan commits herself to completing the camp’s five-step program and becoming “normal.” But things get complicated when she falls for True Directions’ resident bad girl, Graham (Clea DuVall).

The horrors of conversion therapy have become more widely known since But I’m A Cheerleader’s debut, with recent films like The Miseducation Of Cameron Post and Boy Erased tackling the subject matter through a dramatic lens, and governments finally moving to abolish the damaging practice. Babbit first learned about conversion therapy through an article in an LGBT newspaper about the now-defunct Exodus International program. She also had experience with a different kind of rehabilitation program: Her mother ran a treatment center called New Directions for teens with drug and alcohol problems, and she’d long felt that kind of setting had a lot of dark comedic potential.

Babbit decided to combine the two ideas, grounding them in her own experiences as a lesbian. She hired recent USC Film School grad Brian Wayne Peterson—openly gay himself—to write the script based on her 10-page treatment. She was able to get funding on the strength of her Sundance short, “Sleeping Beauties,” which centers on a morgue beautician trying to get over her toxic ex-girlfriend. (David Fincher and Michael Douglas helped Babbit gain access to equipment and costuming to make the short while she was working as a script supervisor on The Game.)

But I’m A Cheerleader was something of a friends-and-family affair. Babbit’s creative partner and then-girlfriend Andrea Sperling produced the film, while DuVall—who had starred in “Sleeping Beauties”—helped assemble the cast from her network of friends. She connected Babbit to Melanie Lynskey, who plays uptight True Directions attendee Hilary. Lyonne, meanwhile, saw the script in the back of DuVall’s car and asked if she could be in the movie. Babbit liked the idea of casting tough-talking Lyonne against type as a bubbly suburban cheerleader. Plus her first choice for the role had turned it down for religious reasons.

But I’m A Cheerleader made Lyonne and DuVall instant icons for the lesbian community. They’ve both gone on to play many more queer women in their respective careers, reuniting as an onscreen couple for DuVall’s directorial debut, The Intervention. And their real-life friendship translates into sparky onscreen chemistry in Megan and Graham’s “opposites attract” love story. In fact, But I’m A Cheerleader is an all-around treasure trove of great young performers. Michelle Williams plays a bit role as a cheerleader and Julie Delpy has an almost wordless cameo as a woman at a gay bar. Babbit also wanted to ensure there was racial diversity amongst the True Directions crew. She initially reached out to Arsenio Hall to play “ex-gay” counselor Mike. When Hall turned down the project, she landed on the even more inspired choice of RuPaul (then billed as RuPaul Charles).

The best summation of But I’m A Cheerleader’s comedic ethos is the image of RuPaul bounding out of a hot pink van in a “Straight Is Great” T-shirt to arrange Megan’s intervention. In her heightened satirical way, Babbit zeroes in on the tragedy and horror of the fact that so many gay conversion camps are run by people who have been through the repressive program themselves. At one point, Megan and her fellow campers are forced to serve as anti-gay protestors, showing how cycles of self-hate perpetuate. Yet as Mike extols the virtues of heteronormative living, he can’t keep his eyes off the camp’s hunky groundskeeper, Rock (Eddie Cibrian). In trying to “fix” its charges, True Directions has inadvertently created a horny gay hotbed where every interaction is charged with innuendo.

At the center of it all is the camp founder and Rock’s mother, Mary Brown (Cathy Moriarty), who’s like Nurse Ratched meets Phyllis Schlafly. Her biggest anxiety is keeping her son firmly in the closet. She channels that into an environment that’s both deeply repressive and absolutely obsessed with sex. Her five-step program emphasizes traditional gender roles (the girls wear pink and the boys wear blue) and ultimately ends with a bizarre ritual where the campers simulate heterosexual intercourse while wearing Adam and Eve inspired bodysuits. Of course, it doesn’t take much to mine black comedy from the pseudo-science used in real gay conversion therapy. Asked to identify the “root” of their homosexuality, campers respond: “My mother got married in pants.” “All-girl boarding school.” “I was born in France.”

Babbit is particularly interested in the way that sexual orientation and gender norms are messily conflated with one another. One of the movie’s best reveals is that butch softball player Jan (Katrina Phillips) is actually straight but no one believes her because of how she dresses and acts. While some of the True Directioners fit into gay stereotypes, like exuberant “actor, dancer, homosexual” Andre (Douglas Spain), Babbit peppers her world with a diverse array of gay characters: Dolph (Hook’s Dante Basco) is a bro-y varsity wrestler and Joel Goldberg (Joel Michaely) is a soft-spoken Jewish kid.

Babbit was adamant that Megan retain her sunny, feminine cheerleader persona rather than change her identity in order to self-actualize. When Megan leaves True Directions and finds refuge at a halfway house run by “ex-ex-gays” Larry (Richard Moll) and Lloyd (Wesley Mann), she asks them to teach her how lesbians are supposed to dress and where they’re supposed to live. “There’s not just one way to be a lesbian,” Lloyd gently advises. “You just have to continue to be who you are.” So when it comes time for Megan to make a big romantic gesture, she does so through a cheer.

Along with Legally Blonde, Miss Congeniality, and the fellow cheerleading comedy Bring It On, But I’m A Cheerleader was part of a wave of early 2000s comedies that explicitly celebrated femininity and girliness. That But I’m A Cheerleader does so in a queer context makes it unique, earning the film a legion of young female fans, particularly once the R-rated indie reached a wider teen audience via DVD. The movie was originally slapped with an NC-17 rating until Babbit shortened a shot of Megan masturbating and re-edited Megan and Graham’s fairly tame sex scene. Since then, Babbit has been outspoken about the MPAA’s double standards, not just with gay subject matter but with female sexuality as well. A year earlier, American Pie had delivered a much raunchier R-rated sex comedy about straight teens (albeit, after its own battle with the MPAA). And even just within her own film, Babbit was able to get away with an oral sex joke involving the male characters but had to cut one about the female characters.

Thanks to the freedom of independent cinema, however, Babbit was mostly allowed to bring her vision to the screen intact. The weaknesses of But I’m A Cheerleader aren’t due to studio intervention. They’re common to a lot of first features, offering an overabundance of ideas imperfectly executed. The young performers aren’t always able to nail the stiffly stylized ’60s camp tone. And Babbit inelegantly stacks satire on top of satire by contrasting the garishly technicolor world of True Directions with the garishly brown world of Megan’s high school with the garishly rainbow-themed home of Lloyd and Larry. As Ebert affectionately observed, “[But I’m A Cheerleader] feels like an amateur night version of itself, awkward, heartfelt, and sweet.”

Yet if But I’m A Cheerleader’s earnest gay fantasia perhaps felt a little naïve or simplistic back in 2000, it seems more revolutionary in retrospect. The burst of onscreen gay representation in the late 1990s didn’t immediately lead to the seismic shift that Will & Grace, In & Out, and Ellen DeGeneres’ coming out seemed to promise. Though gay teens existed on TV throughout the late ’90s and early ’00s, it wasn’t really until Glee in 2009 that they were positioned as romantic protagonists in fairy-tale high school love stories. And it wasn’t until 2018 that Love, Simon became the first major Hollywood studio film centered on a gay teen romance. These days, blockbusters still expect praise for two-second interactions they bill as “exclusively gay moments.”

But I’m A Cheerleader proudly carried the gay teen romance banner at a time when few movies and TV shows were delivering those kinds of stories. The movie also celebrates the power of the LGBT community as a community. True Directions’ co-ed setup inadvertently encourages its young gay men and women to rally together in their shared experiences. Even before Dolph comes to realize he doesn’t have to change his sexuality, he finds relief just being among his peers: “It’s cool to finally talk about [being gay]. I can’t tell any of my friends on the team.”

On one level, the movie is campy rom-com comfort food; on another, it’s a quietly radical celebration of gay love, both platonic and romantic. In fact, But I’m A Cheerleader is a bit like Lloyd and Larry’s home—a rainbow oasis in a challenging world. Through her over-the-top storytelling, Babbit reassures her young audience that there’s a warm, welcoming LGBT community ready to stand alongside them.

Next time: We celebrate the 60th anniversary of Billy Wilder’s iconic rom-com-dram The Apartment.