Although it doesn’t dominate the conversation around them anymore, HBO has still produced more prestige dramas than any other network, cable or otherwise. In fact, you can trace a curlicued path from the current golden age of TV back to one of the pay-cable network’s earliest original dramas. This series premiered in the late ’90s, featured an expansive cast, and juggled humor and realism in a gritty setting. There were capital-letter themes, lots of nudity, and warring factions, not to mention Edie Falco in a starring role. The Sopranos is a fair guess here, as David Chase’s crime drama was the first cable series to be nominated for (and subsequently win) the Emmy for outstanding drama series, and is generally considered one of TV’s greatest achievements. But while The Sopranos is certainly part of the prestige drama’s lineage (arguably the trunk of that tree), it wasn’t the first HBO series to push the boundaries of TV. A year and a half before the Bada Bing opened its doors, Tom Fontana’s prison drama Oz began its bid to change what a television show could be.

Though he wasn’t initially pushing for prison reform, Fontana took the opportunity (56 of them) to question the criminal justice system, examining appropriate sentencing, prison conditions, recidivism, and how politics plays into the notions of punishment and rehabilitation. It was a path he set on while still working on Homicide; in a sense, he created the road map he and other series creators followed to subsequent dramas. The Wire was an obvious successor to Fontana’s procedural, though David Simon probably just considers it a trade-off, since he wrote the nonfiction book that inspired the show and made his segue from journalism to TV in the Homicide writers’ room. Both shows featured flawed but passionate detectives trying to save their cities, the complex crime lords whose options were nonetheless limited, and all the other people caught up in the conflicts.

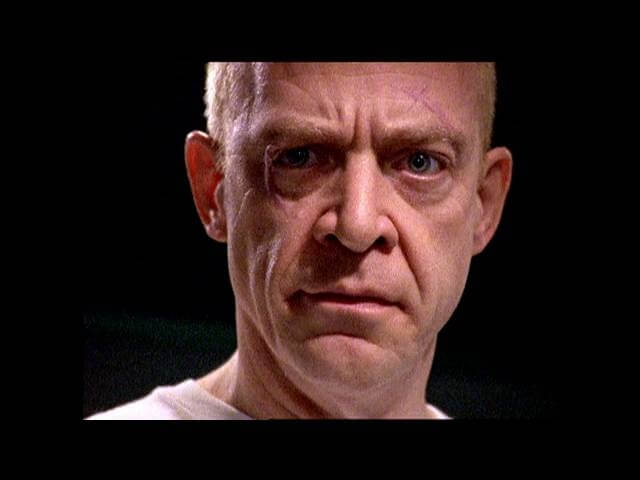

Oz didn’t have the same triad—more was always more, as far as storylines and sects were concerned. But the intricate plots, as convoluted as they could get toward the end of the series’ run, demanded a murderers’ row of actors. And so, like The Wire or Westworld, Oz put together an ensemble cast of dozens, including Falco, Terry Kinney, Ernie Hudson, Dean Winters, Rita Moreno, Harold Perrineau, Lauren Vélez, and J.K. Simmons. And, along with Falco, several of its players went on to star in other well-crafted shows, including The Sopranos, The Wire, Better Call Saul, Breaking Bad, and (to some extent) Dexter, just to name a few. That list doesn’t even touch on all the guest and recurring actors, like Luke Perry, Eartha Kitt, LL Cool J, Edward Herrmann, Ally Sheedy, and Peter Criss (yes, that one). Nor does it mention the many established actors—including Brian Cox, Chazz Palminteri, Steve Buscemi, and Kathy Bates—who went behind the camera to direct an episode or two.

Revelatory turns from big names are now at home in the prestige drama, but when he first pitched the show to HBO, Fontana’s vision wasn’t focused on A-listers. He certainly had performers in mind for the inmates, but they were rawer talents, like Dean Winters and Lee Tergesen. Or they had theater backgrounds, like Terry Kinney, who played Tim McManus, the mastermind behind Emerald City, the fictional experimental prison unit. But as often as we throw the term around these days, no one set out to make prestige drama in 1997 (certainly not before the coin was termed). Instead, Oz was intended as a kind of continuation of Homicide, an exploration of what comes after justice is purportedly served. These weren’t morality plays, though Oz was well known (and sometimes criticized for) its theatricality. Nor did Fontana set out to critique the nation’s flawed prison system, even as he pushed past the usual “lock ’em up and throw away the key” treatment of criminals on TV. But it certainly influenced later seasons of the show. Oz rebuked its audience even as it drew them in with murders, Machiavellian scheming, and just about every form of torture imaginable, including leaving someone naked in a windowless room for weeks on end.

Speaking of nudity, Oz made inroads for the full frontal male shot, dangling dicks well in advance of Rome, The Leftovers, Outlander, and Game Of Thrones. Bare skin is the least essential part of the prestige drama, but more often than not, that boldness extends to other elements of the show. And with Oz, all those hard bodies in an all-male prison meant a surprising amount of consensual sex (given the setting), which resulted in one of the most prominent gay relationships to ever be featured on cable or network television. Fontana didn’t ignore the realities of the prison system when it comes to rape, though he used that device sparingly, all things considered. When inmates committed sexual assault in attempts to dominate and/or break others, Oz’s directors usually framed the scenes from the victims’ point of view. It was a conscious effort not to gloss over or glamorize the sexual violence. More importantly, the irony of having these attacks occur in a place where the perpetrators were ostensibly being rehabilitated—not to mention monitored at all times by guards—wasn’t lost on the viewer.

This was just one of the ways in which Oz mined violence for drama without devolving into a nihilistic nightmare. Emerald City was a maximum security prison, so there were no white-collar criminals or people who’d pleaded to a lesser offense to chew up and spit out before roll call. Everyone had committed a violent crime, even Tobias Beecher (Tergesen), the upper-class lawyer who committed vehicular manslaughter while driving under the influence. Like Piper Chapman on Orange Is The New Black, Beecher was a way in for viewers. And just like his Litchfield counterpart, Beecher ended up far more morally compromised after he entered the penal system than before. Not that either character was perfect before they were sentenced—Piper became a drug mule out of boredom, and that was just her first attempt at a criminal enterprise. And Beecher did kill a girl, for which he deserved to be punished.

But, aside from their rap sheets, Oz’s characters didn’t share much else. The characters had diverse backgrounds, which allowed the cast to actually represent the population. Tribalism was rampant in the series, so the skinheads sided with their Aryan brothers; the black Muslims kept to the straight and narrow; and the Latinos, when they weren’t arguing over colorism, banded together. The racial tensions were enough to spark dozens of blood feuds, and that was all before anyone talked about religion. And though it wasn’t ideal, a byproduct of the prison setting was the platform it offered to both emerging and esteemed actors of color, including Hudson, who portrayed warden Leo Glynn, and Eamonn Walker, who played Muslim leader Kareem Saïd.

An inclusive cast still isn’t a requirement for prestige drama, but Oz had other lasting effects. It helped cement characterization as one of the gold standards of TV (not just prestige or cable): Oz’s difficult men, in the form of philosopher street kings and working stiffs with 20 years on the job, begat the difficult men of New Jersey, Madison Avenue, and Albuquerque. Or, since we’re also talking about shows like Orange Is The New Black and Game Of Thrones, let’s just call them antiheroes. Oz was full of them—as are soap operas, a fact that wasn’t lost on viewers.

The show often delved into melodramatic territory with its diabolical scheming and villains, but Oz usually managed to pull itself back from the soapy edge. It was actually pretty self-aware, cheekily rolling out its own Greek chorus in the form of Augustus Hill (Perrineau) for most of its run. But the villainy was rarely cartoonish, and the perpetrators never one dimensional. With its baroque plotting, superb acting, and panopticon setting, Oz was more “Shakespeare in the prison yard” than Days Of Our Lives.

That mix of high and low culture, of guilty pleasures and appointment viewing, was a tradition that, again, Oz might not have birthed, but certainly nudged along. As existential as Fargo can get, it’s still a (bleak) comedy. And despite the many deaths the fight for the Iron Throne has caused, Game Of Thrones is—for some, anyway—just “tits and dragons.” But the fact that these shows’ creators keep their eyes on the horizon, looking for ways to move things forward—whether it’s finding the extraordinary in the commonplace, or just through distinctive cinematography—is commendable, and something that they share with Fontana. Prestige dramas are ambitious, yes, but they’re also, by nature, grasping. They’re aiming for a higher quality, whether it’s in the cast or writing, than what’s found in most dramas. Once again, this is an element that can be traced back to HBO in 1997. Oz’s naked desire to be something more can be found in dozens of shows that have premiered since its finale, and that’s the most pertinent part of its prestige drama legacy.