Richard Linklater is an excellent filmmaker. This is the wildly controversial thesis put forth by 21 Years: Richard Linklater, a new documentary about the director, out just as his film Boyhood begins an awards campaign. Technically speaking, a long-form appreciation of Linklater doesn’t seem like it has a clear audience. Those who already admire the director may not find a stunning level of insight, and the curious but unindoctrinated would be better served by starting with one his actual films rather than a rundown of them. But there’s a certain satisfaction in a rundown of a career as rich and varied as Linklater’s, not unlike the pleasure of watching a well-edited Oscar tribute reel.

21 Years plays like a longer version of that sort of tribute, an overview with extra attention to specific shots and filmmaking techniques—there are clips from all of his features—as well as the nuances of performance. Plenty of famous actors and others offer testimonials to Linklater’s generosity and talent, but in between introductory material and a closing piece about his importance to his beloved Austin, Texas, the bulk of the film simply makes its way through Linklater’s filmography. It’s not chronological: the first film-exclusive segment goes deep on Dazed And Confused, and the next skips to School Of Rock, while the Before trilogy turns up somewhere in the middle. Filmmakers Michael Dunaway and Tara Wood make some interesting pairings, too, finding commonalities in covering the Texas criminals of The Newton Boys and Bernie and the intentional disconnection between the likes of A Scanner Darkly and Bad News Bears, which came out in successive summers.

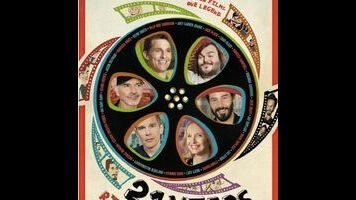

It’s possible that some of these choices have been influenced by the availability of movie stars to talk about the movies in question. In addition to the mandatory Ethan Hawke, much screen time is set aside for Matthew McConaughey, Jack Black, Billy Bob Thornton, Zac Efron, and a surprisingly effusive Keanu Reeves; hence, perhaps, the attention to Scanner over Waking Life, or the brief segment on Me And Orson Welles. But the left-field choices are still intriguing, and any movie-centric doc that also takes time for multiple check-ins with Nicky Katt earns its nerdy bona fides.

If anything, Dunaway and Wood should have swept the corners even more. Completists jazzed by watching Katt give an interview in sunglasses while sitting on a remote dock will take note that the Linklater movies without dedicated segments are Suburbia, Waking Life, Tape, Fast Food Nation, and, most glaring, Boyhood, which was apparently finishing production concurrently with the circa-2012 doc (a few interviewees refer to it as “the 12-year project”). Pieces on these remaining projects would have been preferable to anecdotes rendered in pointless animation, trotted out for seemingly no better reason than it’s something light-hearted documentaries often do (and an especially ill-advised technique for a movie that includes clips from the gorgeous rotoscoping of Linklater’s own animated experiments). But when 21 Years, which contains no on-camera participation from Linklater himself, sticks to its subject’s work, the obviousness of its aims don’t much matter. 17 Movies would have been a less catchy title, but more indicative of what the film does well.