3 1/2 Minutes, Ten Bullets examines an all-too-familiar American crime

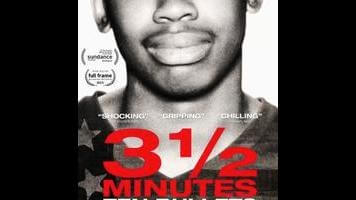

The toxic paranoia poisoning American life is on display in 3 ½ Minutes, Ten Bullets, a fine and timely documentary about the 2012 killing of black youth Jordan Davis in a convenience store parking lot by Michael Dunn, a middle-aged white man who believed that the 17-year-old student meant to do him harm—and later that Florida’s infamous Stand Your Ground laws would protect him in court, as they did George Zimmerman. The outcome of the case is now a matter of public record, but Marc Silver’s film, which was mostly shot over the course of the trial and features plenty of footage of the proceedings, still bristles with tension and uncertainty. Not about Dunn’s culpability, which is established early on and never really rebutted—even by his own defense team. The question here is whether a statewide legal system that seems currently designed to offer unrepentant killers an escape route can itself stand up to any sort of sustained cross-examination.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.