The Weinstein Company has one of the largest and most accommodating shelves in the movie business, able to bear the weight of countless festival acquisitions and in-house productions for as long as Harvey and Bob need to gin up a marketing strategy, distribution money, or an 87-minute voice-over-heavy cut. But watching a movie like 3 Generations—abruptly shelved in between its debut at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival and its planned theatrical release a few days later—the delay starts to make sense. Not because the movie is unwatchably terrible, but because even as it unspools, there’s a sense that on a long enough timeline, it might somehow improve. It spends 92 Weinstein-approved minutes on the verge of telling a compelling story, and winds up stalling out telling a worthwhile one.

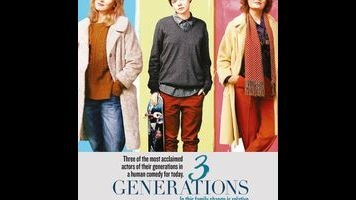

The three generations of the title are represented by Dolly (Susan Sarandon); her adult daughter, Maggie (Naomi Watts); and Maggie’s son, Ray (Elle Fanning). Ray was born a girl, and once went by Ramona, but has known for years that he is a boy in a female body. At 16, he is eager to begin the transition process and start over at a new school with classmates unaware of his past, needing only parental consent signatures to begin hormonal treatments. It’s not surprising that Maggie is more supportive of this change than Dolly, but the screenplay adds an interesting wrinkle by making Dolly a lesbian with longtime partner Frances (Linda Emond). She doesn’t understand why, if Ray is attracted to women, he can’t just be a gay girl.

All four family members live in one of those New York City real estate conveniences—here, a multiple-residence building where Maggie and Ray can maintain separate but sometimes still uncomfortably close quarters alongside Dolly and Frances. But if the building seems elaborate for a group of people who make very little reference to doing or having done actual work, at least the staircase creaks when characters climb it—and they always sound winded when they reach the top, a nice touch. The nominal obstacle in the way of Ray’s transition comes from outside this enclave. Craig (Tate Donovan, wearing a turtleneck of consternation), the man whose name appears on Ray’s birth certificate but has not been much of a father for the past decade or so, also needs to sign Ray’s forms. But Maggie harbors semi-secret doubts about whether Ray is rushing into this, and on some level uses the “bad” parent as an excuse to drag her feet while remaining the “good” parent.

Part of her anxiety, shared by Dolly, makes the film a sort of 21st-century cousin to 20th Century Women, also with Fanning: Coming from such a female-heavy environment, Maggie isn’t sure she’ll know how to parent a boy. It’s a knotty, potentially interesting idea, about which director and co-writer Gaby Dellal seems to share her character’s uncertainty. Occasionally Fanning captures the fraught, frayed edges of a teenager who feels out of place in his very body, but the focus keeps pulling back to Maggie and a predictable series of melodramatic revelations (one involving a character with barely any screen time), or to Dolly and her inability to keep opinions to herself. (At this point, a non-sassy, teetotaling grandma would be a more unconventional choice than another round of feisty, boozy meddling).

This never had to be just Ray’s story. But the family’s particular dynamic gets away from Dellal. Their group dialogue has a manufactured quality, derived from each actor speaking in overwritten yet underthought single-line rejoinders to each other, a round-robin version of domestic cacophony. This tendency isn’t smoothed over by bizarre turns like a scene where Maggie, Dolly, and Frances have to drive a rickety old car (rather than the non-rickety, non-old car seen earlier in the film) on a brief road trip, for reasons that remain unclear.

It’s possible those reasons have been yanked out of the movie. Many scenes and sequences end abruptly, indicating that there may well have been a longer cut of the movie, which may well have played better than this one. If that’s the case, it’s especially hard to understand why the filmmakers (or whoever else) decided to leave in so much footage from the autobiographical documentary Ray shoots, mostly with his phone, that appears to consist largely of skateboarding footage. This is what 3 Generations gives to Ray by way of characterization, while Maggie gets the melodrama and Dolly gets the unfunny wisecracks. There’s a kind of equality at work here: No one is well-served.