30 For 30: Vick is a nuanced portrait of a scandal-plagued quarterback

For the past two NFL seasons, the greatest show on any given Sunday has been whatever game features either the Kansas City Chiefs’ Patrick Mahomes or the Baltimore Ravens’ Lamar Jackson. These two quarterbacks’ creativity and playmaking skills stand out in comparison to the conservative tactics and brute physicality of so much of the league, which lately has been producing games that feel choppy and graceless. By contrast, watching Mahomes and Jackson escape tackles and make impossible throws isn’t just exciting, it’s moving. It’s marvelous theater.

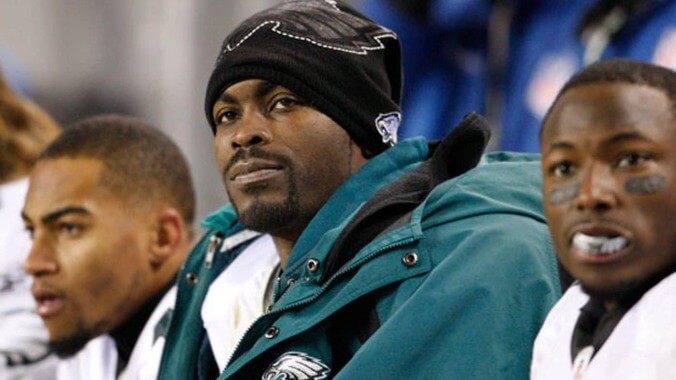

For older fans, the Mahomes and Jackson phenomenon has been pleasantly familiar. It’s a throwback to the early 2000s, and the heyday of Michael Vick.

The new 30 For 30 installment “Vick”—directed by Stanley Nelson—is a two-part, four-hour deep dive into the former Atlanta Falcons QB’s rise and fall and eventual return. Part one covers Vick’s remarkable high school and college years, detailing how he emerged as one of the NFL’s most exciting players, all while handling an uncommon level of media scrutiny about his work ethic and off-field lifestyle. Part two (which airs the following Thursday, February 6) gets into what many people perhaps most remember about Vick: that he and his friends were arrested for running a dogfighting ring on his property.

Nelson—a three-time Emmy-winner—has had a long and distinguished documentary filmmaking career, including the likes of Freedom Riders, Miles Davis: Birth Of The Cool, and The Black Panthers: Vanguard Of The Revolution. He sees Vick’s story as more than just a simplistic cautionary tale, about how a rich and successful athlete is undone by a lack of personal discipline and an excess of loyalty to his buddies. The two-part structure of “Vick” serves a purpose. The first half gives Vick’s glory days their due, putting them in the context of how other superstar Black athletes were treated by the press and public. The second half wrestles with some difficult issues concerning what Vick did to those dogs—and whether his punishment fit the crime.

The halves are unified by two questions, which Nelson answers as honestly as possible, weighing the available evidence: What kind of person is Michael Vick, really, and how much of what happened to him was due to his race?

The documentary is partly about where Vick came from: an underprivileged community where friends and family were expected to take care of each other. Early in his career, Vick’s coaches and financial managers urged him to stop hanging around with any old acquaintances who could be “a bad influence.” But that advice wasn’t so easy to take. Nelson makes it clear that Newport News, Virginia is an important part of this story… as is suburban Atlanta, which around the time the Falcons drafted their franchise QB had been in the national news for incidents of overt racism. “Vick” notes that from the beginning, some white people were quick to judge and condemn the quarterback—and that some Black people were quick to defend him—no matter what he’d done right or wrong.

A lot of the tension in the documentary’s first part involves Vick’s associations and his attitude toward his job. It’s still up for debate as to whether he made the most of his running and passing skills, which were unlike anything that anybody had seen at any level of organized football. But here again, Nelson is even-handed. He uses old ESPN clips and new interviews to remind viewers of the way sports journalists have talked about Black quarterbacks. He makes the case that some reporters wanted Vick to slip up, to confirm their biases.

But Vick himself admits that in his early years, he relied more on his instincts and his physical gifts than he ever did on practicing and studying. A sensation from the moment the Falcons drafted him, Vick spent a lot of his time away from the stadium shooting commercials and appearing in rap videos—as well as partying with his crew at his rural Virginia estate. During his Atlanta years, he led the team to some of their greatest seasons. But his style of play also made him injury-prone, and he and his chums’ pot-smoking habit led to some embarrassing legal problems. Part one of “Vick” suggests that the QB was wearing out his welcome with the NFL even before the dog-fighting scandal hit.

Pretty much the entire first hour of part two digs into the dog-fighting, and avoids easy explanations or excuses for what happened. In new interviews, one of Vick’s childhood friends insists there’s nothing wrong with the sport—and nothing wrong with killing dogs when they lose. In archival clips from around the time the scandal broke, Black celebrities like Steve Harvey wondered why he was being sentenced to a longer jail sentence for harming dogs than policemen serve for killing defenseless Black suspects; meanwhile, some white commentators argued back then that Vick should’ve gotten the death penalty. (A young Tucker Carlson said he should be hanged… not a great image.)

What the average football fan may not remember is that Vick emerged from all this disgrace and controversy a changed man. As a condition of being taken off the NFL’s suspended list when he got out of prison, Vick admitted he was wrong and pledged to work with charities and programs promoting the protection of animals. (According to this 30 For 30, he still does this, long after retirement.) The Philadelphia Eagles then signed him as a third-string quarterback, but through a series of unexpected twists he became the starter, and proceeded to have two of the best seasons of his career. According to most reports, he became more committed to game-prep, and was a model NFL player all the way up to his retirement: hard-working, community-focused.

Is that enough to excuse what he and his friends did with those dogs? Nelson doesn’t go that far. “Vick” does though once again reflect on how white celebrities, politicians, and athletes are often treated warmly by the media and the public after they apologize for their mistakes. Shouldn’t even someone who did something as heinous as Michael Vick did also be allowed to atone?

Perhaps most importantly for sports fans, the documentary asks whether we can be allowed to enjoy Vick’s old highlights, and to celebrate his legacy. “Vick” takes maybe too sharp a turn into “and then he lived happily ever after”-land after it covers the comeback years; but a closing montage of Jackson, Mahomes, Russell Wilson, and Kyler Murray is undeniably stirring, especially given that it comes nearly four hours after the episode’s earlier montages of sports broadcasters doubting the NFL futures of Black quarterbacks. During the clips of these new-wave QBs, reporters fumble for the right way to describe what they’re seeing, before settling on “like Michael Vick.” If nothing else, this 30 For 30 explains the many things “like Michael Vick” can mean. Remembering him as a villain—or a hero—doesn’t tell the whole story.