35 years before the (second) XFL, the USFL brought football into the springtime

We explore some of Wikipedia’s oddities in our 6,016,226-week series, Wiki Wormhole.

This week’s entry: United States Football League

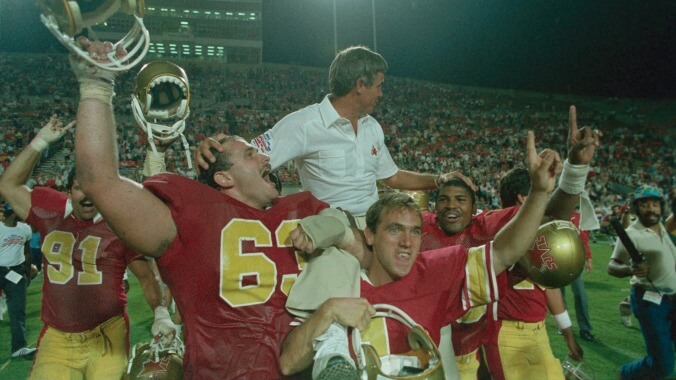

What it’s about: The only kind of football fans can’t get from the NFL: More football! In 1983, New Orleans businessman David Dixon launched the USFL, not to compete with the venerable National Football League, but to complement it, playing a season in the spring and summer, the offseason for both pro and college football. It was a winning formula… until the league collapsed after just three seasons.

Biggest controversy: Dixon built a strong model for a league—if only his fellow team owners had followed it. Dixon had helped steer the NFL’s expansion into New Orleans in 1967 (and was an initial co-owner of the Saints). That same year, he co-founded World Championship Tennis, a pro men’s tennis tour that ran until 1990. But two years before either, he had the idea of a spring/summer football league, and he spent decades planning and recruiting team owners.

His outline for the league was called the Dixon Plan. In it, teams would play in NFL-caliber stadiums, the league would secure a national TV contract, and teams would tightly control spending. The first two more or less worked out—the NFL did pressure some stadiums into not leasing to the USFL, which left a few teams scrambling for a home field. With NBC and CBS broadcasting NFL games, rival ABC (and its corporate sibling, the nascent ESPN) ponied up $13 million to broadcast the first season. But controlling costs was part of the league’s undoing.

Some sports leagues have a salary cap—a hard limit on how much teams can spend on players. The Dixon Plan was merely a suggestion, so some teams began trying to outbid the NFL (and their USFL rivals) for players, and even the fiscally responsible teams felt like they had to overspend to be competitive. So while the USFL quickly drew fans and, “was regarded as a relatively good product,” most teams were spending money faster than it was coming in. In frustration, Dixon sold his share and quit.

Making things even worse, the league got into business with the worst businessman in America. After the first season, the New Jersey Generals franchise was bought by a man who once lost a billion dollars running a casino. New owner Donald Trump immediately began agitating to move games to the fall to compete directly with the NFL. Trump openly admitted that his plan was for the USFL to fail, in the hope that the NFL would absorb a few franchises from the wreckage, as it had when it merged with the (far more successful) AFL in 1970. The original owners were largely opposed, but Dixon was out, and the most vocal supporter of the status quo, Tampa Bay Bandits owner John F. Bassett, had to sell his stake in the team when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. The owners voted to move to the fall.

Trump’s plan half-succeeded: Moving to the fall season did destroy the league. By abandoning its original schedule, the USFL turned down $175 million from ABC for four more seasons of spring football, and had no TV deal lined up for the fall season. Half the USFL’s teams played in NFL markets, and a few folded rather than try and compete for attendance with storied franchises like the Detroit Lions or Pittsburgh Steelers. Finally, an increasingly desperate USFL sued the NFL for antitrust violations, hoping a cash settlement would help finance the flailing league through its first fall season. A jury found that the NFL was an illegal monopoly, but that the USFL’s financial woes had been brought on by the league’s own poor decisions, the move to fall chief among them. The jury awarded the USFL three dollars, and the league folded. Neither Trump nor any of the other USFL owners were welcomed into the NFL, although the league would eventually place its own teams in USFL markets like Jacksonville, Tennessee, and Arizona.

Strangest fact: There’s a fairly straight line from Trump’s running the USFL into the ground to his presidency, which goes through Buffalo. No NFL team benefited more from the USFL’s collapse than the Buffalo Bills, as rookie quarterback Jim Kelly and star running back Joe Cribbs opted to play for the USFL instead. After two years, both players returned to Buffalo, which built a braintrust around two other USFL alum: general manager Bill Polian, and coach Marv Levy. The Polian/Levy braintrust built a Kelly-led team that would advance to four Super Bowls (and lose all four). The Bills had one more USFL connection in 2014—when original team owner Ralph Wilson died, Trump attempted to buy the team. He was outbid by energy magnate Terry Pegula, but the NFL was also prepared to reject his bid because of his past with the USFL. His failure to buy the Bills “was cited as a major factor” in Trump moving on to a new project: an unlikely run for the presidency. (Along similar lines, there’s an alternate timeline where George W. Bush got the job he really wanted—Commissioner Of Baseball—and never ran for president).

Thing we were happiest to learn: Some NFL greats got their start in the USFL. Alongside Kelly, fellow quarterback Steve Young, defensive end Reggie White, and tackle Gary Zimmerman are all in the NFL’s Hall Of Fame (as are Levy and Polian). The USFL had made waves by signing three consecutive winners of the Heisman Trophy, college football’s top honor. Of those three, Herschel Walker was an All-Pro best remembered for a trade that sent him to Minnesota for a bushel of draft picks that allowed the Dallas Cowboys to build a team that won three Super Bowls; Doug Flutie had limited success in the NFL, but became perhaps the greatest player in Canadian Football League history. (The third, running back Mike Rozier, was a modest success with the Houston Oilers and Atlanta Falcons.)

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: Even during the league’s early success, stability was not its strong suit. Dixon’s plan called for the league to expand from 12 teams to 16 in the second year, but the owners decided to go to 18 so they could collect two more franchise fees. But by year three, they were back down to 14. The Michigan Panthers, one of the league’s winningest and best-attended teams, folded after a year because ownership was adamantly against the move to the fall season. The expansion Pittsburgh Maulers followed suit. The Chicago Blitz couldn’t peel fans away from the Bears even in the offseason, and the Arizona Wranglers couldn’t get fans to show up in the heat of summer, and those teams folded as well (although the Oklahoma Outlaws then moved to Arizona immediately after. It’s a dry heat, after all).

Had the league played a fall season in 1986, it would have done so with only eight teams, three of which were in Florida. Every team that shared a city with an NFL franchise but one folded, rather than have to not only compete directly with a more established team for fans, but also find a stadium not already occupied by the NFL. Only the Tampa Bay Bandits were willing to go head-to-head with a crosstown rival, as they were one of the USFL’s most successful and popular teams, and their NFL counterparts, the Buccaneers were among the NFL’s least successful at the time.

Also noteworthy: The NFL eventually adopted many of the USFL’s on-field innovations. Instant replay, the two-point conversion (already a staple of college football), a salary cap (although the USFL cap was ignored by owners), and scheduling a marquee game on Sunday night were all adopted by the NFL not long after the USFL folded.

Strangest fact: The USFL both helped and hurt one NFL team in particular: the Buffalo Bills. No NFL team benefited more from the USFL’s collapse than the Bills, as rookie quarterback Jim Kelly and star running back Joe Cribbs opted to play for the USFL instead. After two years, both players returned to Buffalo, who built a braintrust around two other USFL alum, general manager Bill Polian, and coach Marv Levy. The Polian/Levy braintrust built a Kelly-led team that would advance to four Super Bowls (and lose all four).

Further Down The Wormhole: Donald Trump made one more run at professional football. When the Buffalo Bills’ owner, AFL co-founder Ralph Wilson, died in 2014, Trump attempted to buy the team. He was outbid by energy magnate Terry Pegula, but the NFL was also prepared to reject his bid because of his past with the USFL. His failure to buy the Bills “was cited as a major factor” in Trump moving on to a new project: an unlikely run for the presidency. (Along similar lines, there’s an alternate timeline where George W. Bush got the job he really wanted—Commissioner Of Baseball—and never ran for president). Trump—an oft-bankrupt businessman with no experience in politics whatsoever—was an unlikely candidate for the White House. But he was far from the most unlikely candidate. That honor goes to Trump’s 2020 primary challenger Rocky De La Fuente, who vied for the Democratic nomination in 2016 while also running for Marco Rubio’s Senate seat as a Republican, before running for Senate in nine different states in 2018. We’ll gear up for Super Tuesday by looking at De La Fuente’s quixotic career as a candidate next week.