Nearly every film about professional wrestling hits a crucial point, where the participants have to decide how fully they want to answer one of the oldest and most persistent questions about their entire industry: “Is wrestling fake?” It’s something wrestlers themselves are understandably sick of talking about, for two reasons in particular:

- Their fans don’t care that the outcomes in wrestling matches are predetermined, because part of the fun of watching is in taking the fiction at face value.

- Even though wrestling moves are choreographed, there’s still a lot of improvisation, and the performers still still get hurt.

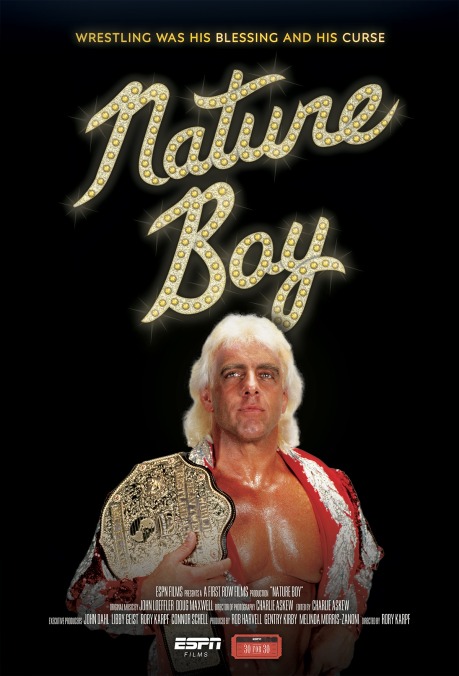

That said, in the long-awaited 30 For 30 episode “Nature Boy,” the subject’s caginess about fakery gets in the way of what’s most interesting about his story. Ric “Nature Boy” Flair was around at the moment when wrestling exploded in popularity, due largely to the expansion of cable TV and UHF channels. As one of the biggest stars of the lower-rent National Wrestling Alliance and World Championship Wrestling, he has special insight into the ways that his team staged combat and built stories, in comparison to the slicker WWF. But while all of that is an element of what “Nature Boy” is about, ultimately the nuts-and-bolts of the pro wrestling phenomenon take a backseat to Flair’s personal story of success and excess.

The episode’s director Rory Karpf specializes in sports docs, with an emphasis on subjects that mean a lot to kids reared in the American south between the ’70s and ’90s: like Dale Earnhardt, Herschel Walker, Eli Manning, and SEC basketball. It’s clear he has a long-standing personal investment in Ric Flair’s ring persona, expressed directly in their one-on-one interviews, and indirectly in the comments he solicits from the likes of Michelle Beadle, Maria Menounos, and Snoop Dogg. Everyone Karpf talks to is in agreement about what Flair meant in the 1980s, when he brought his luxuriously long hair, glitzy style, and Jerry Lee Lewis “woo!” to grubby arenas in mid-sized cities across the United States.

And yet aside from some animated interludes (themselves a cliché in documentaries these days), Karpf gets too locked into too many sports-doc conventions, dulling his personal touch. “Nature Boy” is stylistically pat, proceeding chronologically through clips from Flair’s career, supported by talking-head interviews. It also leaves a lot of gaps in that timeline, by skipping ahead to the most salacious details in his story: the partying, the poor money management, and the heartbreak.

To be fair, Flair does have an almost Dickensian tale to tell. Adopted as an infant by a studious doctor and his wife—who named him Richard Fliehr—he rebelled as a teenager against his staid parents, who weren’t impressed by his athletic prowess or outsized personality. Dropping out of college after a year, he found his way to Verne Gagne’s pro wrestling camp in 1971, and soon was traveling the country alongside the likes of The Iron Sheik, Andre The Giant, Ricky Steamboat, and Dusty Rhodes. “Once I realized how good I was at it,” he says in the film, “It became a disease.”

Surviving a plane crash changed both Flair’s outlook on life and his body, with the recovery process turning him into the handsome rake who’d become one of wrestling’s top attractions by the end of the 1970s. As the money came rushing in, Flair abandoned all pretense of being a respectable family man. Unaffected by his own tumultuous upbringing, he married multiple times, had kids he rarely saw, and spent his days on the road chain-drinking and sleeping around. (“If you’re wrestling in Hutchinson, Kansas, you’re gonna find something to do,” he shrugs.) Because he didn’t plan well for the future, Flair stayed on the circuit much longer than he should’ve—even after he’d been given a moving retirement ceremony in 2008—and his absentee parenting came back to haunt him when his son died of a heroin overdose while pursuing his own wrestling dreams.

Karpf pulls “Nature Boy” out of the darkness in its closing minutes, by focusing on how proud Flair is of one of his other wrestling children, Charlotte. But the happy ending feels tacked on—a consequence of dedicating so much of the episode to the subject’s dark personal life.

Thank goodness then that there’s also some stuff about wresting in this documentary. Karpf’s understanding of what made Flair special—and his obvious excitement about it—manifests in some wonderfully geeky segments about the highlights of the star’s career. “Nature Boy” waxes rhapsodic about Flair’s friendly rivalry with Rhodes, and his creation of a legendary legion of heels called “the Four Horsemen.” The episode considers Flair’s influence on all the modern athletes and entertainers who boast about their wealth and skills. And while reporting on how Flair lived in the shadow of the WWF’s superstar Hulk Hogan, Karpf gets Hogan to admit that the Nature Boy was a better wrestler, with a wider range of moves and more versatility as a character.

Overall, this 30 For 30 excels when it dwells on the specifics: like how Flair learned to sell a hit by punching a string until it didn’t move; or how he preferred to perform in matches with continual action and no built-in rests; or how he was a master at getting punished for 10 minutes before turning the tables. His generation of wrestlers introduced new ways of constructing narratives, and more creative and acrobatic moves—like Flair’s “turnbuckle flip,” where he turned his body upside-down on the ropes while escaping an opponent.

The evolution of pro wrestling showmanship—and the analysis of what worked, and why—offers much more fruitful material than the standard-issue story of a celebrity who partied too hard. At its best, “Nature Boy” weaves its main threads together, closely connecting its subject’s stories inside and outside the ring. Karpf gets this documentary right whenever he moves away from the general and the familiar, and instead illustrates exactly how Flair got good at being knocked around—because he knew it’d be preordained for him to come out on top.