A ’70s Hollywood bromance is at the heart of documentary The Bandit

Any documentary about the making of a nearly four-decades-old movie runs the risk of coming off as little more than a glorified DVD extra. With The Bandit, director Jesse Moss (The Overnighters) has succeeded in placing the production of 1977’s Smokey And The Bandit in a larger cultural context as well as grounding it in the career-spanning relationship between the film’s director and its star. The result is a tremendously entertaining love letter to both a specific movie and a bygone era of Hollywood populated by larger-than-life characters in front of the camera as well as behind the scenes.

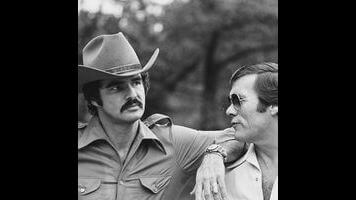

The cultural impact of Smokey And The Bandit is largely overlooked today, but the tall tale of truckers illegally transporting Coors beer from Texas to Georgia finished second only to Star Wars in the 1977 box office race. Smokey represented the crest of a wave of hick flicks that Burt Reynolds rode to stardom throughout the ’70s as he made his name with good ol’ boy roles in Southern-fried features like Deliverance, White Lightning, and Gator. From the beginning of his career, however, Reynolds was shadowed by another man: Hal Needham, a sharecropper’s son from Arkansas, who began his career in Hollywood as Reynolds’ stuntman. They would become roommates after Needham’s wife threw him out of their house and he showed up at Reynolds’ door with the intention of crashing for a few days. He stayed for 11 years, during which he scribbled out the first draft of the Smokey screenplay. Reynolds thought it had the worst dialogue he’d ever read, but he agreed to star in it for Universal with the proviso that Needham be given the director’s chair.

Moss uses the making of the movie as a springboard for any number of colorful tangents: the raucous lives of professional stuntmen who put their lives on the line to create spectacular action sequences (and their resentment toward actors who go on talk shows claiming to do all their own stunts); the rise of trucking and CB culture in the 1970s; the arc of Reynolds’ acting career and the ways he may have unwittingly sabotaged it; and the unlikely supporting cast, including Sally Field, Jerry Reed, Jackie Gleason, and Paul Williams.

Although Moss conducted a number of contemporary talking-head interviews for The Bandit, much of the story unfolds through an impressive array of archival footage, imbuing the film with a Me Decade aesthetic that’s evident from the opening shot of Reynolds wearing a burgundy, wide-collared leisure suit and lighting a smoke. Clips from mid-’70s talk shows and TV specials reveal Needham’s similar fashion sense (wearing a shirt unbuttoned to the navel with gold chains dangling against his hairy chest, the director claims Reynolds copied his style) as well as the decor of the spectacular Reynolds/Needham bachelor pad. (Giving a tour, Reynolds is constantly pointing out mirrored ceilings, furry bedspreads, and seeming acres of tile.) The winking Burt persona—a Marlboro Man with a light comic touch—defined ’70s-era masculinity. As the man himself said, “I just think I’m the best Burt Reynolds there is.”

It’s more than a little shocking, then, when we get our first glimpse of present-day Reynolds, looking impossibly frail as he oversees an acting class in the hometown theater bearing his name. It’s easy to see why Moss lets vintage Burt do most of the talking in The Bandit, as the recollections of the elderly Reynolds are mostly soft-focused soundbites shaped by decades of repetition. Still, his participation is a testament to his enduring loyalty to Needham, which he admits may have cost him an Oscar-caliber role when he opted to continue working with his Smokey director through a series of lesser car romps, including Stroker Ace and the Cannonball Run movies. There’s no indication that he regrets that sense of loyalty, but another career misstep—posing for a nude centerfold in Cosmopolitan just as Deliverance hit theaters—proves harder for Reynolds to justify.

No one involved with the production of Smokey And The Bandit suggests that it’s some sort of monumental work of art, and that includes Needham. In every interview (including one conducted shortly before his death in 2013), he happily admits to aiming no higher than a Looney Tunes combination of action and comedy. Yet the movie outperformed even the most optimistic expectations, especially once Reynolds and Needham convinced Universal to get it out of Radio City Music Hall and onto Southern drive-in screens. Nearly 40 years later, it remains a thoroughly enjoyable feature-length Roadrunner cartoon thanks largely to the chemistry of its cast (even if, as is rumored by several interviewees, Reynolds refused to do more than one scene with Gleason for fear of The Great One stealing the show).

Even if Smokey isn’t your cup of Coors, The Bandit is a must-see, not only for its dozens of amusing bits of showbiz ephemera (at one point, Needham is seen dressed in a tuxedo giving a speech honoring Reynolds, and just over his shoulder, a semi-attentive Charles Nelson Reilly can be glimpsed) but also for the platonic love story at its heart. Lifelong friends, Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham always secretly wanted to be each other: Reynolds yearning for the genuine good ol’ boy camaraderie of the stunt crew, Needham envious of being the doted-on star in front of the camera. Their mutual affection and respect never wavered, however, and even if their later collaborations are forgettable, their first outing as director and star is worthy of this affectionate, entertaining tribute.