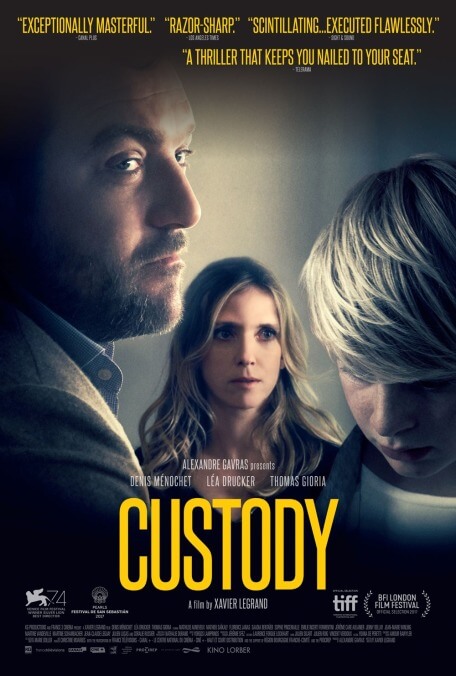

At first, Custody seems to tease split sympathies, like just about any other movie about the aftermath of a messy divorce. The opening 15 minutes depict a shockingly short custody hearing in real time. Miriam (Léa Drucker) has come armed with a statement from her 11-year-old son, Julien (Thomas Giora), who has no desire to see his father again—a request echoed by the former couple’s 18-year-old daughter, Joséphine (Mathilde Auneveux). But Antoine (Denis Ménochet), the man sitting on the other side of the table, calmly disputes the characterization, even questioning if his son really wrote it; he has his own evidence to offer, the affidavits that paint a very different picture of him than the hot-headed brute his ex-wife describes. “Nothing here is black and white,” the judge is forced to conclude, eventually granting joint custody. Soon, however, it becomes clear that there is a villain in this particular broken marriage, and he’s the petty, self-pitying, abusive husband taking his separation very poorly.

Custody unfolds with a queasy neorealist urgency, escalating a nightmarish situation scene by scene, with no musical score to distract from the characters’ grueling emotional ordeal. No matter how often Miriam changes her phone number or address, Antoine always finds her—mostly by badgering his son, on weekends that play out like hostage situations, heavy on interrogation. Legrand, expanding upon his Oscar-nominated short “Just Before Losing Everything,” acutely captures the psychological distress that domestic violence incurs: how the abused can become slaves to the abuser’s temperament, walking on egg shells to avoid an outburst. At the same time, the French writer-director never makes Antoine less than human; as played by Ménochet—who, like Drucker, is reprising his role from the short—he’s a weak tyrant who tries to paper over his spells of cruelty and rage with pitiful emotional appeals. In one chilling scene, Antoine stalks around Miriam’s apartment, an unspoken threat in every step, before breaking down into tears, pleading for a second chance. In Miriam’s extremely careful navigation around his feelings—a soft rejection that Drucker performs like someone disarming a bomb in an action movie—Custody addresses every insensitive why-didn’t-you-just-leave query ever tossed at someone once trapped in a toxic relationship.

It’s a hard, sometimes wrenching movie, in part because Legrand—working in the sturdily straightforward handheld style popular among scores of European auteurs—observes this all-too-prevalent crucible with unblinking clarity. No melodramatic twists or turns spoil the verisimilitude (though there is a slender subplot about a pregnancy scare for the daughter that goes weirdly unresolved). There may still be those who find something vaguely distasteful about the way Custody, a film heavy with the weight of statistics about the real violence inflected on real women by men every day, slowly transforms into a kind of kitchen-sink thriller, ratcheting up the tension en route to a harrowing finale. But there’s grim, even cathartic truth in the awful inevitability of the climax and the genre machinations that get us there: Anyone who’s ever escaped from or grown up under the abusive supervision of a mean bastard knows how much life really can resemble a horror movie.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.