A brief history of live-concert bootlegging

People have been making recordings of performances by musical artists without their knowledge or permission for years, but the first recognized, wide-release bootleg to hit the underground-store shelves came in the summer of 1969. Titled Great White Wonder, it was released by Trademark Of Quality Records, a label set up by a couple of guys in Los Angeles, “Dub” Taylor and Ken Douglas. The album was composed entirely of unavailable and unreleased recordings Bob Dylan had made over the previous eight years, including a number of cuts he recorded with The Band that would become part of the Basement Tapes.

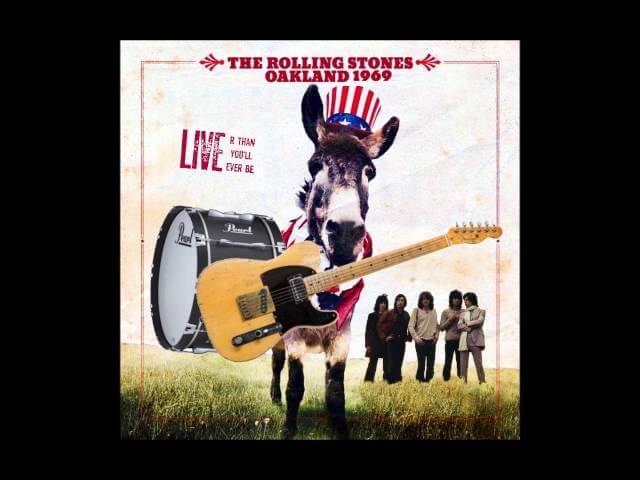

Trademark Of Quality was the forerunner to the wider bootleg recording industry, and within months of debuting Great White Wonder, it ventured for the first time into the live-concert realm, issuing releases that are still venerated and passed around. Among its more notable selections include a Rolling Stones show in Oakland in 1969 titled Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be, Led Zeppelin at the L.A. Forum in 1970 released as Live On Blueberry Hill, and In 1966 There Was, a near-complete recording of Bob Dylan’s famed show at the Royal Albert Hall, where he deafened those who would call him “Judas” for his Stratocaster-strapped electric turn.

Other bootleg labels soon began popping up. Rubber Dubber Records issued an outstanding Jimi Hendrix double-LP titled Live At The Los Angeles Forum in 1970, Rock Solid Records was responsible for Led Zeppelin’s 1977 near perfectly recorded Forum gig Listen To This, Eddie!, and the Amazing Kornyfone Record Label, one of the most prolific names in the game, issued more than a hundred different titles between 1974 and 1976.

As the ’70s wore on, the bootleg record industry exploded. New labels popped up almost daily, offering wholly new recordings, remastered retreads of what was already out there, and different compilations of the best tracks from a multitude of performances. The morass grew so large and intractable that Kurt Glemser, a live-concert obsessive out of Ontario, felt spurred to release the bible of bootlegs in 1975. Glemser’s Hot Wacks helped consumers get a handle on what was out there, what was good, and what wasn’t worth the vinyl or tape that it was printed on. To the underground enthusiast, Hot Wacks served as a necessary and vital compendium, one that Glemser regularly updated throughout the years to help others to navigate their way through the hellish tangle of the expanding black market.

A bootleg recording makes its way out into the open market through a variety of different ways. In the early days, the best releases came from ill-gotten soundboard recordings commissioned by the band members themselves for potential official release at some point in the future. These recordings had the benefit of multiple, carefully placed microphones placed in front of every instrument, fed into a soundboard, and monitored by a hired engineer, like the great Eddie Kramer. Creating a record from this method required a great amount of wheeling and dealing between bootleggers and those who had access to the tapes themselves, or in some instances, outright theft.

Another technique that produced tapes of highly sought-after quality was the FM radio rip. These were live transmissions taken directly from a mixing board and broadcast out to listeners who had a finger placed on the big red record button on their home stereos. But while there are a wealth of soundboard and FM recordings out there, the lion’s share of what’s available came from regular people taking it upon themselves to tote along a concealed recording apparatus to a show on a given night and trying as best they could to capture it for posterity. The identities of these various concert cowboys are rarely known to the listener, but some did manage to achieve a degree of notoriety, like the legendary Mike Millard.

Millard—or Mike The Mic, as he was known within the bootlegging community—was a near-constant fixture at the Los Angeles Forum in the 1970s. In his time, Mike was directly responsible for capturing some truly crystalline recordings of some of the most legendary shows ever put on in that hallowed hall: Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Rush, Eric Clapton, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, all in the prime of their careers.

In order to get past security and lug in his unwieldy Nakamichi 550 tape deck and microphones into the venue, Millard would show up on the given night in a wheelchair and sit on the equipment. After getting rolled to the handicapped section, he would wait for the arena to go dark, and then remove the equipment and make his way about eight rows back from the front of the stage, where he would record the show with two microphones hidden in his hat.

Millard’s recordings were so good that when Jimmy Page was putting together a Led Zeppelin DVD, he took snippets of them to fill out the spaces in the promo menus. Unfortunately, Millard suffered from a deep depression. In 1990, he hastily destroyed all the original copies of his meticulously recorded works; he committed suicide shortly thereafter.

Millard wasn’t the only prominent tape maker on the scene. There was also John Wizardo, who was responsible for the aforementioned Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be; Dan Lampinski in New England, whose recordings of Frank Zappa in 1976 are still being passed around; and Mr. Peach, who worked out of Japan and captured bands that rolled through that country during the ’70s and ’80s. For these individuals, the thrill of bootlegging came out of getting past the systems put in place to stop them, and capturing a brief moment in time in the best fidelity imaginable.

Vinyl records were superseded in the late ’80s by CDs that could hold nearly double the number of songs. The various independent labels took full advantage of this, and rather than hearing excerpted, abbreviated concerts, listeners now received access to full, multi-volume recordings of whole shows, or even sets of shows. This development was a huge boon to fans of Led Zeppelin, Bruce Springsteen, and Prince, who all put on live shows that would regularly run past the three-hour mark. With the advent of digital technology and the internet, music fans were posting and swapping these recordings with each other online as soon as bandwidth levels could allow.

There’s never been a point at which live bootlegs have been as easily accessible as they are now, even though only a handful of labels even exist anymore like Godfather, Empress Valley, and Antrabata. At a time when internet piracy of legitimate releases has drifted into a passively accepted way of life, no one is really throwing roadblocks in the way of fans seeking out extra-legal recordings from some show that took place in Sacramento four decades ago. You can access and download nearly the entire live history of some artists by finding the right set of links and having the appropriate amount of hard-drive space. And you might not even need the latter, as Wolfgang’s Vault and YouTube host mega-streams of entire concerts.

Even the artists themselves have gotten into the bootleg business, turning what used to be a thorn in the music industry’s side into a legitimate new revenue stream. Bands like Phish and Pearl Jam were early adopters of this model; recently, legacy acts like the Stones and Springsteen have opened up their own vaults to fans willing to dish out $10 or so to hear cleaned-up versions of records that have dwelled on the black market for decades. As long as there are bands and artists willing to hit the open road to play before a paying audience, it seems there will always be an ardent subsection of fans determined to get their hands on a decent-sounding copy of that gig.