A Cannes winner returns to the classroom, but not to form, with disappointing thriller The Workshop

After winning the Palme D’Or for Sex, Lies And Videotape, Steven Soderbergh famously quipped, “Well, I guess it’s all downhill from here.” Sadly, it really has been all downhill for Laurent Cantet since a Cannes jury bestowed that same prize upon The Class, his 2008 drama (also nominated for the Foreign-Language Oscar) about a dedicated middle school teacher in Paris’ culturally diverse 20th arrondissement. Cantet followed up this triumph with a French adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ Foxfire: Confessions Of A Girl Gang, which premiered in 2012 to roughly the same tepid reception that had greeted a 1996 American version (starring the young Angelina Jolie and future Rilo Kiley singer Jenny Lewis). Nor was there much enthusiasm for Return To Ithaca (2014), an ensemble yakfest about aging former radicals that lazily echoes Return Of The Secaucus Seven and The Big Chill. Neither of those films got a U.S. release, and Cantet—who’d made a Stateside splash even before winning the Palme, with Time Out (2001)—was forgotten.

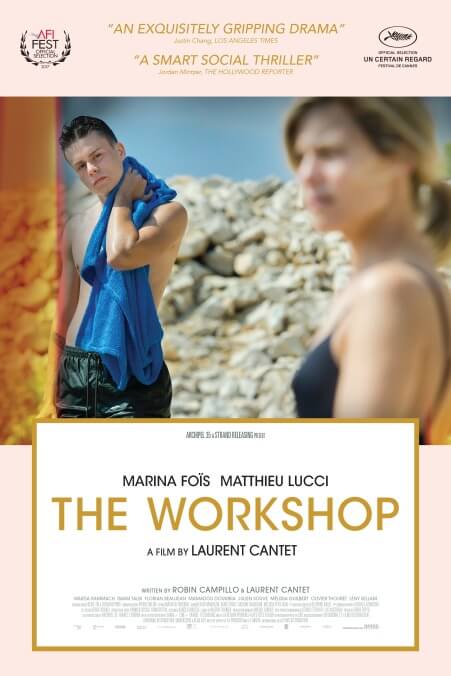

The Workshop, his latest film, seems designed to remedy that, playing like The Class’ pointedly topical evil twin. Once again, the protagonist is a teacher—in this case, a successful author named Olivia (Marina Foïs) who’s running a creative-writing workshop for teenagers in the south of France. It’s an ethnically and culturally diverse group of kids, though they all come from working-class families; the goal Olivia has set for them is to jointly compose a novel set in their hometown, La Ciotat, a former shipbuilding community fallen on hard times. They decide to write a thriller, arguing passionately but mostly without malice about what direction it should take. A boy named Antoine (Matthieu Lucci), however, seems a bit… off. His own stories, as well as his suggestions for the group project, are disturbing odes to violence—the kind of thing that got the Parkland shooter reported to the authorities, except couched here as fiction. There’s also a suggestion of repressed sexual tension between Olivia and Antoine, even as she starts to actively fear him.

Cantet and his regular co-writer, Robin Campillo (who’s a director himself), raise a provocative question with this scenario: At what point does ostensibly hypothetical aggression turn into a genuine threat? Rather than seriously explore that idea, however, The Workshop shifts into thriller mode itself, making Antoine a glowering, one-dimensional villain who eventually winds up stalking Olivia at her house. His ugly nationalism provokes some compelling arguments among his fellow students (all of the teens, including Lucci, are non-professionals cast locally), but has no bearing on the omnipresent danger he presents to Olivia, who’s not an outsider in any respect whatsoever. And it’s hard for a thriller to get the blood pumping when it keeps self-consciously underlining its own genre mechanics; almost everything the kids say about their novel also functions as winking auto-critique. Cantet remains a gifted filmmaker—The Workshop’s semi-improvisational aspects are no less impressive than those in The Class, and he’s at least superficially engaged with the current state of the world—but this isn’t the return to form that his fans have awaited over the past decade. Let’s hope these years turn out to be a valley, not a continuous downhill slope.