A Coen brother goes solo, with help from Denzel and Shakespeare, in a striking Macbeth

Joel Coen’s take on the Scottish Play may not be definitive, but it’s one of the best-looking movies of the year

Over the course of 18 feature films, brothers Joel and Ethan Coen have jointly taken their place among the most visually and verbally distinctive working filmmakers in America. Their credits have not always been identical—on films before 2004, Joel was designated as director and Ethan as producer, with both of their names typically on the screenplay and neither of them officially claiming credit for their frequent (and Oscar-nominated!) editing under the pseudonym Roderick Jaynes. But they’ve been described as two men working more or less as a single, synced-up artistic brain. So what happens when you jettison half of that partnership? Their masterpiece Inside Llewyn Davis felt like it was considering that very question within its text. Now Joel Coen’s The Tragedy Of Macbeth offers the striking, strange, presumably temporary answer: replace Ethan Coen with William Shakespeare.

Joel Coen sticks fairly close to the Bard’s text, paring it down and shifting some of it around slightly without making major alterations. It wouldn’t be fair to categorize an all-time genius playwright as a mere obstruction, a formal challenge for the filmmaker to hurdle over. Yet considering his repeatedly demonstrated love of inventive verbosity, brushing up on his Shakespeare does, in a sense, tie one arm behind Coen’s back, and in many ways his Macbeth resembles a palate-cleaning experiment.

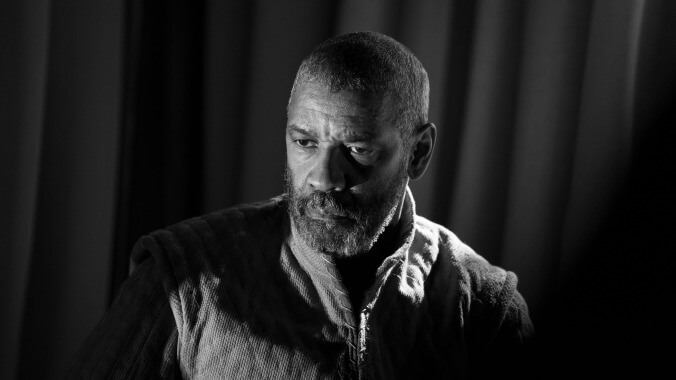

That experiment, consciously or not, may involve swapping out Coen’s brother for his spouse, three-time Oscar winner Frances McDormand. She both produces the film with Coen and plays Lady Macbeth, while Denzel Washington fills the famous role of Lady Macbeth’s Husband. That’s really the adaptation’s biggest change, if far from unprecedented and not requiring a formal rewrite: Here, Lord and Lady Macbeth are an older couple whose chances at glory are quickly drying up. The power grab they cook up, setting the film’s tragedy into motion, plays as both urgent, because of their age, and oddly pragmatic, because Washington and McDormand are both experts at appearing reasonable—even when talking through the specifics of traitorously murdering King Duncan (Brendan Gleeson). McDormand’s reading of “screw your courage to the sticking place” feels insidious because it’s not hectoring or even particularly aggressive. It’s a firm suggestion, with hints of dangerous, stubborn manipulations below the surface.

Just getting to see McDormand and Washington assay these famous parts makes this Macbeth worth preserving for posterity, alongside Fences in the Denzel Washington Giants Of Theatre section. But Coen’s equivalent of a solo album has its own virtuosic style. With text modifications mostly off the table, he adapts the play visually, and through subtraction: Coen removes color, returning to black-and-white for the first time since The Man Who Wasn’t There, and arranges his actors on stark, sometimes near-abstract soundstage sets. Even the three witches whose prophecy opens the story are played by one performer, with Kathryn Hunter doing brilliantly creepy work in optical-illusion triplicate.

The digital shine of Bruno Delbonnel’s cinematography gives the black-and-white images an eerie clarity, bringing out details like the white hairs that dot so many characters’ heads and beards (especially Washington’s). The resulting look is both stagy and expressionistic. A simple scene inside a tent is decorated with trees casting shadows from outside, before a dissolve smoothly transitions from canvas to castle walls. The famous “double, double toil and trouble” scene is staged with the witches perched on rafters above Macbeth, as the floor at his feet fills up with a misty liquid, turning the room into their cauldron.

As visually exciting as these scenes are, there are moments where the old Coens magic is conspicuously missed—call it the “told by an idiot” factor that has previously converted some of their sound and fury into dark comedy or even farce. A lack of mirth is perhaps an unfair knock against any movie with “tragedy” in the title, but Stephen Root needs a mere minute or so of screentime in a bit part as the Porter to recall that Coen character-actor magic that most of The Tragedy Of Macbeth is too classy to indulge. Coen’s past films have been accused of working at a chilly distance, a charge that might actually, finally stick here after years of aggressive overuse.

Then again, a slight and straight-faced aloofness may have been necessary to keep The Tragedy Of Macbeth from turning into a Shakespeare-by-a-Coen self-parody; the connections to Joel’s previous work are clear enough without the cast mugging for emphasis. Lord and Lady Macbeth conspire to kill a bunch of people, all—as Marge Gunderson might say—for a little bit of power. The doomy inevitability, too, fits some of the Coens’ bleaker works. Joel doesn’t seem constitutionally capable of teasing out a sense of surprise from this Macbeth’s late-middle-age downfall. Cinema has long since been saturated with bloody, power-grasping spirals of all ages, which also makes it difficult to discern where Joel might go next, should he continue to make movies without Ethan. For now, he’s started with leaving the words intact but changing the music, refashioning an old standard into a lucid dream.