For decades, Barry Windsor-Smith’s Monsters was a comic-book urban legend. Originally pitched in 1984 as an Incredible Hulk one-shot exploring Bruce Banner’s abusive childhood, the story was shelved because of the word “goddamn” and then later repurposed during Bill Mantlo’s run on the series, infuriating Windsor-Smith. The cartoonist shopped a revised, significantly expanded version of the book to different publishers—at one point it was going to be published at Vertigo—but Monsters never materialized beyond some artwork posted on Windsor-Smith’s website. Then, last year, Fantagraphics announced that it would release the 360-page black-and-white graphic novel in 2021, the first new work from Windsor-Smith in 16 years.

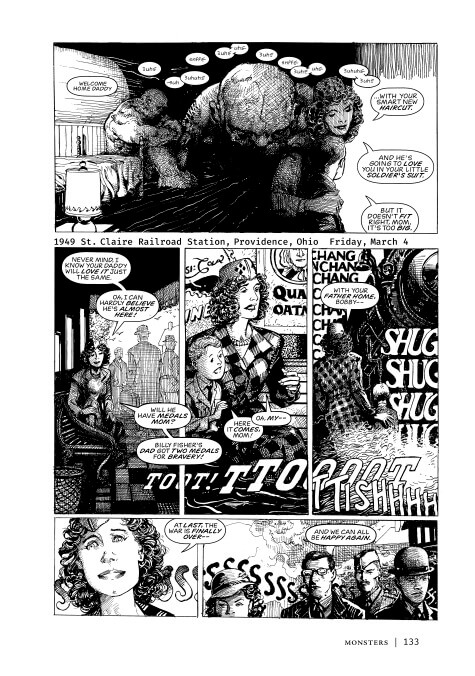

Monsters takes the seed of a terrifying character’s painful upbringing and grows it into a sprawling family drama about the horrors of war and its impact across generations. Bruce Banner is now Bobby Bailey, and his transformation into an unstoppable, disfigured brute is the end result of a tragedy unfolding since World War II. The book begins with the defining trauma of Bobby Bailey’s childhood, when his father, Tom, a newly returned veteran of World War II, beats him within an inch of his life and permanently destroys his left eye. The short scene kicks off the narrative with suspense, mystery, and expressive horror that visually breaks from reality. As Janet Bailey crawls away from her husband, cradling her bleeding son in her arms, perspective and the proportions of the surrounding environment start to shift, creating a disorienting, nightmarish landscape where the gigantic Tom Bailey looms over his family.

Windsor-Smith is known for his meticulous inking, and his cross-hatching gives Monsters’ world and characters remarkable dimension. His inks are mostly very tight and specific, but in the opening sequence, the lines have a wildness that contributes to the chaos. Tom is drawn with a flurry of lines that gives his physical form instability that reflects the madness overtaking his mind. He shouts in German, and his word balloons are filled with jumbled text written in Fraktur, the typeface predominantly used (and later banned) by the Nazis. This opening creates questions the story won’t return to for a while, and from there the action jumps to 1964, when an adult Bobby Bailey enrolls in the military and ends up the test subject for Project: Prometheus, a Nazi supersoldier program continued by the U.S. government.

As impressive as Windsor-Smith’s cross-hatching is, it’s equally powerful when he minimizes the linework. A three-panel sequence of a helicopter taking Bobby Bailey away is infused with dread, thanks to the sea of black that swallows the aircraft, drawn with just a few white lines as it disappears in the distance. Toward the end, Windsor-Smith references Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World for a character’s moment of transcendence, but he strips away the details and only draws the outlines to emphasize the shift into another plane of consciousness.

The first act of Monsters shares a lot with its creator’s most popular superhero work, Weapon X, another grotesque look at the government torturing an individual through experimentation. Originally published in 1991, Weapon X holds up well 30 years later, telling the story of how Wolverine got his adamantium skeleton through a fascinating mix of body horror and political commentary (with a splash of workplace comedy). Like Bobby Bailey, Logan is at the center of Weapon X, but he’s not the main point-of-view character. Instead, Windsor-Smith focuses on the scientists who dehumanize their subject in order to turn him into the ultimate killing machine, looking at the ethical compromises they make for their jobs and the emotional connections they make with their meat puppet. There’s very dark humor in the workplace dynamics, specifically in how the team engages with its sociopathic leader, Dr. Abraham Cornelius.

Humiliation is a big part of the horror in both Weapon X and Monsters. Suffering of the body and the mind isn’t enough; the spirit must be broken too. In Weapon X, Cornelius needs to reinforce his superiority over his superhuman specimen, most pathetically in a scene where he pours coffee on an unconscious Logan’s face. Bobby Bailey’s humiliation at the hands of cruel Project Prometheus workers is the cover image of Monsters, a tight close-up of the wretched Bobby with tears in his eyes and an American flag through his head. It’s a twisted version of an office prank, one that deeply dehumanizes an innocent man who just wanted to serve his country.

There’s one person haunted by these events: Sergeant Elias McFarland, the man who recruited Bobby and is now tormented with guilt, and who has his own strange past with the Bailey family. The superhero influence is strongest at the start of Monsters, and Elias’ mission to rescue Bobby unfolds in an exhilarating car chase that leads to a devastating shootout. The dramatic sound effects punctuate key moments in the action, and the shootout is a showcase of how lettering impacts storytelling, with line weight, letter shape, and balloon placement working together to create a feeling of total mayhem.

There are supernatural elements to Monsters, but they’re more Stephen King than Stan Lee. The story shares some significant similarities with The Shining: a malevolent supernatural influence on a father that compels him to terrorize his wife and son; a boy with extraordinary power; a Black male character with “the sight” who comes to the boy’s aid and suffers the consequences. But the larger themes, plot structure, and distinctive characters make Monsters its own beast. This is a story about how war corrupts individuals and institutions, exploring the idea through the eyes of a morally conflicted Black army sergeant and a housewife whose life crumbles when her husband returns from overseas.

Elias’ relationship with his wife and children is as important as Bobby’s transformation in Monsters’ first act, and as Bobby is mutilated, Elias’ guilt takes a bigger toll on his home life. His wife, Bess, struggles to believe in Bobby’s supernatural gifts, and as Elias becomes more fixated with Bobby, Bess becomes more concerned about her husband’s mental health. The family dynamic here is tense, but it’s rooted in affection and empathy. Elias and Bess communicate with each other, and even when they don’t like what the other person is saying, they’re still willing to listen and respond honestly in hopes of finding a solution that will ease both of their fears. It’s a strong contrast to Janet Bailey’s relationship with her husband, who responds to any of her anxieties with aggression and animosity, refusing to share the trauma that poisons their marriage.

The biggest chunk of Monsters focuses on Janet, presented with a mix of traditional comic pages and hand-written journal entries with accompanying illustrations. The journal entries enrich the emotional content in many ways, starting by creating intimacy between Janet and the reader as they gain access to her interior life. Seeing her handwriting—and the spots where she starts a thought, then crosses it out—gives even more life and spontaneity to Janet’s character, which makes her domestic situation all the more devastating. This is a woman desperate to understand why her husband has become a different man after war, and she’s constantly rationalizing his dangerous behavior. Janet doesn’t know what happened to Tom overseas to turn him into an abusive alcoholic, and her story ends before she ever learns the truth, although she gets a taste of it when she touches her husband’s haunted Nazi pistol.

Monsters has breakneck action and lots of atmospheric horror, but the majority of the book is domestic and workplace situations, highlighting Windsor-Smith’s skill with character acting. Emotional beats are exceptionally clear, and he pays close attention to the different ways people experience pain, internalize it, and release it. It brings vitality to these characters and conversations, and by withholding information, the script creates a sense of intrigue that keeps the momentum moving forward when there isn’t much in the way of spectacle. The book’s timeline moves backward, eventually filling in most of the blanks when it lands in Schongau, Germany to reveal what happened to Tom Bailey and his fellow soldiers at the end of World War II.

All of the main characters in Monsters are tied together in deeper ways than they know, and the script actively engages with the idea of destiny rather than coincidence. These lives are connected like spokes on the wheel of fate, and as the story expands, it reveals the full shape of that wheel and where it’s going. The lampshading might not work for some incredulous readers, but it’s comforting to think that in a world full of seemingly random suffering, there’s a grand design that puts people where they have to be to help those in need.