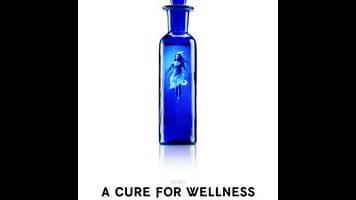

A Cure For Wellness is about as weird as modern Hollywood movies get

It isn’t every week, month, or even year that Hollywood bankrolls a movie as ambitiously bugfuck as A Cure For Wellness. Equal parts baroque fairy-tale, atmospheric mystery, and hideous body-horror nightmare, the film puts what could have been a cost-effective genre exercise on steroids, giving life to a two-and-half-hour, R-rated Frankenstein monster. Who had the industry clout to realize such a warped vision on such a large scale? The byline reads Gore Verbinski, virtuosic operator of Disney’s most profitable live-action rollercoaster ride, the Pirates Of The Caribbean series. After several for them—all starring Johnny Depp, not all beloved—Verbinski seems to have made one for himself. His Cure For Wellness is too long and not entirely satisfying on a narrative level, but all of its bugs look a little like features: This is the kind of singularly strange production that you appreciate for its excess and lumpiness, for the way it strays haphazardly out of blockbuster comfort zones.

For Verbinski, it’s a return to form—or more specifically, to the muted color palette, amateur detective work, and shock scares of his best movie, The Ring. But whereas that fiendishly effective remake mostly stayed in its J-horror lane, A Cure For Wellness has more on its mind than thrills. It also fancies itself a parable about the soul-sickness of modern living. Our hero, Lockhart (Dane DeHaan), is a power-hungry stockbroker working in a sterile Manhattan high-rise, a tower of glass, steel, and greed; we know immediately that he’s a workaholic with mixed-up priorities because he entrusts his secretary to pick out a birthday gift for his mother. On the eve of a major merger, the board blackmails this ruthless corporate climber into retrieving the company CEO, Pembroke (Harry Groener), from the remote medical spa where he’s taken up permanent residence. This is no normal relaxation destination: Situated on a winding mountain road in the Swiss Alps, it’s a hospital within a looming Gothic castle, where the wealthy guests fly kites, eat expensive meals, and receive a mysterious form of water therapy. Pembroke has no intention of leaving, but that turns out to be the least of Lockhart’s problems—especially once he’s injured in a harrowing car crash and awakens to find himself checked into the facility as a patient.

DeHaan, from Chronicle and The Place Beyond The Pines, has sunken, haunted eyes and a queasy intensity. He looks a little like a younger, colder Leonardo DiCaprio—and the resemblance isn’t an accident, as Verbinski is clearly riffing on the cat-and-mouse sanity games of Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, only with a wolf of Wall Street instead of a Bahstan cop skulking around hospital grounds. Is there something nefarious going on at this secluded retreat, overseen by a head doctor (Jason Isaacs, from the Harry Potter movies) with an unnerving bedside manner? Or is it all in Lockhart’s head, a projection of childhood trauma and corporate fatigue? A Cure For Wellness prolongs its mystery, drops hints and red herrings, and plays hallucinatory tricks on the audience, as Lockhart—stuck on crutches, an ingenious suspense device—hobbles through the facility in search of answers. Surely, the truth must involve a pale, childlike damsel (the perfectly named Mia Goth) he first spots perched precariously on one of the castle curtains. And the squirming eels he keeps seeing can’t just be a product of his imagination. Or can they?

A Cure For Wellness comes on like a puzzle box waiting to be solved, but its pleasures are much more visceral than cerebral. Verbinski, freed from the shackles of summer franchise building, treats the project as an outlet for his demented visual style. One is reminded constantly of his affinity for oddball set-ups and striking compositions: his camera racing alongside a train as it ominously passes into a tunnel; a room distorted in the reflection of a taxidermied animal’s unseeing eye; disgusting close-ups of retinas and incisors. (Distending faces into grotesque shapes is a speciality; remember, with a shudder, that quick glimpse of Samara’s closet handiwork in The Ring.) What’s more, the Gothic mystery framework of A Cure For Wellness curbs some of Verbinski’s more manic instincts, forcing him to devote his attention to atmosphere instead of pyrotechnics. His weakness for dodgy CGI still gets indulged, however: The car-crash scene pointlessly ends with a mortally wounded deer, staggering around in a digital death dance.

Like pretty much all of Verbinski’s movies, A Cure For Wellness doesn’t know when to say when. It’s not the most elegant piece of writing, pockmarked as it is with lapses in logic, lengthy detours, and plot holes. (Why doesn’t Lockhart check in with his colleagues back in New York sooner? Simple answer: Because the story wouldn’t work if he did.) And after one too many real-or-fake reversals, the final reveals may inspire more shrugs than gasps, whether you’ve gotten ahead of the film’s secrets or not. But if Verbinski risks losing our investment in this tale of physical, mental, and/or spiritual decay, his talent for fantastical spectacle never grows old—especially as the film begins crosscutting between its most ghoulish and most opulent attractions, culminating in a climax that suggests what a Hammer horror movie might look like on an eight-digit budget. Simply put, nothing stranger is likely to make it to multiplexes any time soon. Savor the oddness.