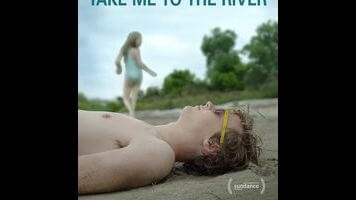

In its opening minutes, writer-director Matt Sobel’s debut feature looks to be a well-made variation on a fairly common type of indie: the “gay outsider in a small town” character sketch. Logan Miller plays Ryder, a California teen who reluctantly tags along with his mother Cindy (Robin Weigert) and father Don (Richard Schiff) to a family reunion in Nebraska. Though Logan hasn’t come out to his relatives—at his mom’s request—they pick up on his queerness anyway, from the way he dresses and his interest in art. No one’s overtly bigoted toward him; they’re just cold, and tentative. Sobel holds tight on his lead throughout these scenes, conveying Logan’s alienation from his surrounding by emphasizing how much he stands out from the farmland, the people, and the potluck lunch.

Then Logan’s 9-year-old cousin Molly (Ursula Parker) asks if he’ll come play with her in the barn. Minutes later—after ignoring all of Logan’s attempts to get her to be more careful and less rambunctious—Molly runs screaming back to the house, with a bloodstain on the front of her dress and no apparent sign of a wound. Her father Keith (Josh Hamilton) starts yelling at Cindy, not just because he thinks her son may have sexually assaulted his daughter, but because of his long-simmering resentment of her for leaving home, marrying a Jew, and giving birth to a weirdo.

For the most part, Take Me To The River’s lurch into melodrama marks a permanent shift away from it being just another sensitive slice-of-life. Though there’s still more than an hour left after the big moment, nothing nearly as momentous happens. Sobel largely abandons the naturalism of his early scenes, shooting for something more spare and spooky. Logan is asked to leave his grandma’s farmhouse until tempers cool, and during his exile he receives a series of visits and invitations from his family, who all suspiciously seem to want to forget about what happened. With just a few minor tweaks, Take Me To The River could play as a moody supernatural horror picture, with Logan as the dangerously curious hero being warned away from an evil he shouldn’t confront.

Instead, the film stays more grounded in mundane mysteries—although Sobel does work hard, all the way to the end, to avoid offering any definitive explanations for what everybody but Logan and the audience seems to know. Take Me To The River is vague to a fault, suggesting just enough to get across what may be going on, while remaining open to interpretation. As a piece of storytelling, this approach can be pretty unsatisfying, as Sobel stubbornly refuses to pay off all that he sets up.

Then again, there may be a good reason why Take Me To The River plays it so coy: Because it’s not really about what happened to Molly. The bloody dress is just a hook, to keep viewers engaged while Sobel continues what he started in the film’s opening minutes. There are a few moments of overt culture-clash in the movie’s second half—like when a creepily smiling Keith asks Logan if he, like his mother, thinks he’s “better” than his Nebraska roots—but for the most part Sobel explores a more subtle unease. Even more than how weird his family becomes regarding Molly’s incident, Logan’s unnerved by the way his sophisticated mom is suddenly saying things like, “Want to come inside and get some pop? It’s hotter ’n heck out there.” It’s as though “Nebraska” were the mean that everyone else is regressing to, while Logan remains a confused and confusing outlier.

Take Me To The River works best in scenes like the one where Logan gets goaded by his uncle and aunt into singing the homoerotic song that he did for a school talent show back west—while he’s sitting in a Midwestern breakfast nook and drinking generic store-brand cola out of a plastic tumbler. Sobel gets beneath Logan’s discomfort, which manifests not just in uncertainty over whether he should let Molly be so spirited when she’s sitting on his neck and playing horsey, but also whether he should be encouraging her when she sings Katy Perry and talks about visiting him in California. If the big questions in Take Me To The River remain naggingly unanswered, that’s probably because the film is equally unsure about a smaller, more important question: How can someone be himself around people who apparently resent what he represents?

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)