A documentary muckraker takes on the tech sector of health in The Bleeding Edge

The business of health is built on other people’s problems. This simple fact is reiterated in one form or another throughout Kirby Dick’s muckraking exposé of the medical devices industry, The Bleeding Edge; we see it in regulatory buck-passing, excruciating side effects, and a level of corporatization that, in Dick’s view, has to some extent turned physicians into sales reps and depersonalized healthcare. He takes his share of potshots (mostly at the Da Vinci surgical robot), but the conscience of the film is in the stories of Essure, a procedure marketed to women as a hassle-free alternative to tubal ligation, and a defective transvaginal mesh used in surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse. Bayer announced last Friday that it would be discontinuing sales of the former in a press release timed to turn that part of the film into a non-story; in the meantime, the latter has already cost Johnson & Johnson $300 million in settlements. Not that either company is in danger of going broke.

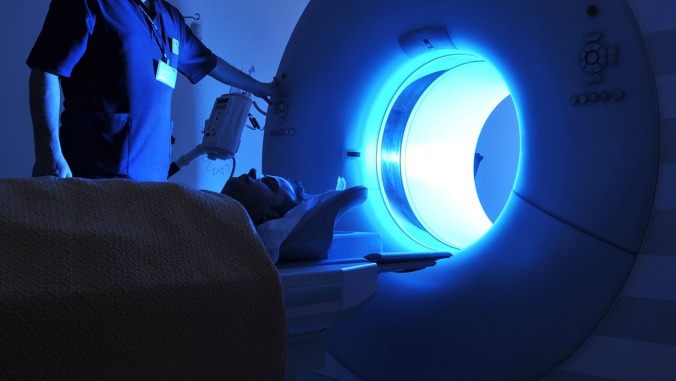

In a sense, The Bleeding Edge is about the privatization of our well-being; our bodies and illnesses are money-makers and, even if we know that our doctors have our best interests in mind, a treatment is some way a transaction between a patient and a glacially huge pharma-medical conglomerate out to make a profit. When it comes to medical devices, the problem is even more complicated; products can meet FDA approval without testing, often based on the approval of similar or earlier devices. It’s a vast category that includes everything from tongue depressors to MRI machines, though Dick’s focus remains, as ever, on the things that make us squirm. Since his breakthrough, Sick: The Life & Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist, the prolific documentarian has argued the case for putting it all out there. Over the years, he’s tackled censorship (This Film Is Not Yet Rated), hypocrisy (Outrage), and institutional cover-ups of sexual abuse in the military (The Invisible War), colleges (The Hunting Ground), and the Catholic church (Twist Of Faith). If there’s an overarching theme to his work, it’s that the things we don’t want to talk or know about can, in fact, hurt us.

The Bleeding Edge isn’t an audacious or essayistic piece of filmmaking; it’s overstretched with talking-head interviews, montages of corporate videos, and creepy B-roll shots of hospital equipment. But it finds provocative subjects in the industry of women’s reproductive health—which has its own history with euphemistically worded ideas about propriety, intimacy, and the ownership of bodies—and in the lives of victims of medical technology gone wrong. Its heroes are the women who meet in support groups and through Facebook; who talk openly about ruined sex lives and medical horrors; who come out to picket shareholder meetings and industry conferences. It’s one thing to point out flawed regulations, and another to challenge the secrecy of our own well-being. To Dick, the possible meanings of “private” as it relates to medical care in this country—that is, profit-driven, untransparent, and a personal matter—are closely related. The idea that it’s nobody’s business but your own is part of the business plan.