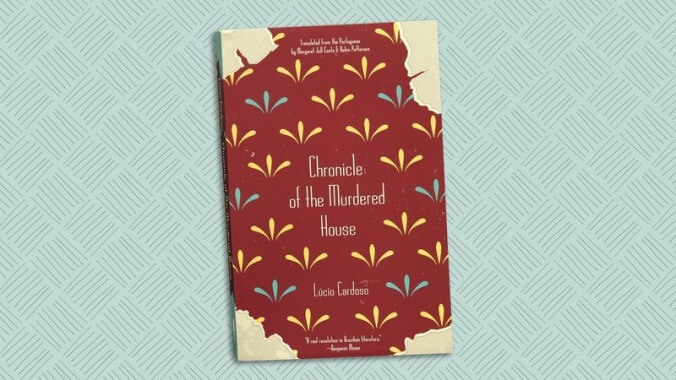

A family’s downfall marks a high point in Brazilian literature

… Once again, there is a storm brewing over the Chácara, and it is an agglomeration of all those wicked, aimless feelings that I see once again building up over the heads of innocent people…

Like its protagonist—or, depending on which account herein you believe, antagonist—Lúcio Cardoso’s Chronicle Of The Murdered House has reemerged from seclusion. First published in 1959, it was a postmodernist work that veered from the nationalist literature that had preceded it. Where his forebears sought to represent their country’s social consciousness, Cardoso narrowed his focus to the moral and financial decline of the fictional Meneses, a once-grand family relegated to the Brazilian countryside.

But his twisted tale, which has been translated into English for the first time by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, still fits within the discussion of his contemporaries, delving into gender roles and class structure as it does. The social commentary might have been lost on audiences when it debuted, but not his genre bending. Cardoso’s approach is as expansive as the lands on which his charmless bourgeoisie have lived for generations; he was a voracious reader with a preference for Gothic fiction and Russian lit, and those influences are on full display in Chronicle’s framework and themes. From its mysterious opening—which is actually the end of one character’s story—to the exploration of morality, the novel is a near-total manifestation of his talents.

Those who imagine love from afar, like a fruit they have never tasted, have no idea how delicious suffering can be—simultaneously terrible and sweet—because to love is to suffer.