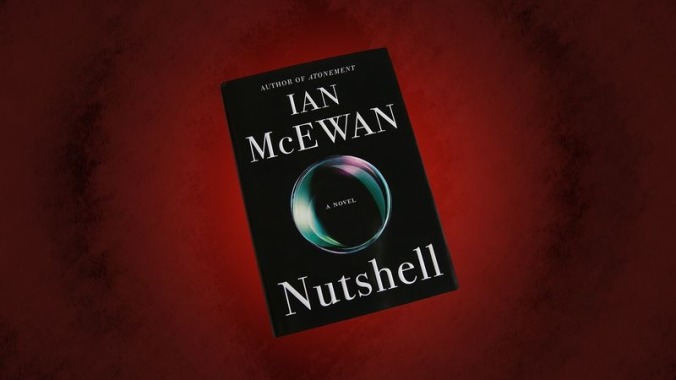

A fetus narrates Ian McEwan’s retelling of Hamlet

The title Nutshell comes from Hamlet: “Oh, God, I could be bound in a nutshell and count myself king of infinite space—were it not that I have bad dreams.” And from the first line we understand that the book’s narrator is indeed confined to a very small space: “So here I am, upside down in a woman.” The narrator of Nutshell is a fetus.

This fetus hangs upside down in Trudy Cairncross, who is married to but separated from the baby’s father, John Cairncross. She is still living in his family home—while having an affair with John’s brother Claude. The fetus, who can’t help but eavesdrop from his confined position, has learned of a sinister plot between Trudy and Claude. What are they going to do to John?

This is one conceit that runs throughout Nutshell: a fetus tells the story. He addresses the way he experiences the world early in the book: “I’m immersed in abstractions,” he claims on page two, “and only the proliferating relations between them create the illusion of a known world. When I hear ‘blue,’ which I’ve never seen, I imagine some kind of mental event that’s fairly close to ‘green’—which I’ve never seen.” Later he explains:

How is it that I, not even young, not even born yesterday, could know so much? I have my sources, I listen. My mother … likes the radio and prefers talk to music … I hear, above the laundrette din of stomach and bowels, the news, wellspring of all bad dreams…

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.