There’s no figure in modern music—or any other medium, for that matter—like Scott Walker, the American-born teen idol who seemed like the antithesis of cool in the mid-1960s, but unexpectedly reinvented himself, first as the morbid highbrow romantic of the string-drenched studio album, and then as an enigmatic icon of the avant-garde and experimental. And like so many original and idiosyncratic artists, Walker first discovered his voice through imitation and hero worship. Having found success and stardom in the U.K. as the baritone voice of melodramatic hit-makers The Walker Brothers, Walker seemed to want try being someone else—namely, he wanted to be the worldly, sardonic Belgian singer-songwriter Jacques Brel.

A little background: Walker, whose real name is Noel Engel, was scoped out as a musical talent in his early teens, and had been putting out rock and roll and light pop singles for years before he joined Gary Leeds and John Maus to form The Walker Brothers and relocate to London. It’s important to note that The Walker Brothers did not make boring music: They recorded gorgeous baroque pop and blue-eyed soul, but they also never sounded like a rock band, despite technically being one; in the era of the British Invasion, the blues revival, and the rockification of folk, The Walker Brothers were covering lesser-known Frankie Valli singles. (Admittedly, they also covered Bob Dylan, but so did everyone back then.)

Walker—who was originally the trio’s bassist and harmony vocalist, but sang lead on all of their hits—was part of the first generation of gloomy young people to get obsessed with Ingmar Bergman movies and existentialist philosophy. He was also a born crooner with no substantial interest in the hard stuff of rock—which, ironically, would eventually lead him to make music that was more intense and abrasive than anything recorded by his peers. (This is, after all, a guy whose most recent album is a collaboration with Sunn O))).) Walker was a distinctive singer, but he was also a budding songwriter, with B-sides like “Archangel” and “Mrs. Murphy” showcasing a uniquely dark dramatic sensibility.

But the big creative leap forward came when Walker discovered himself in someone else—in Brel, who was already hugely popular in France and Belgium, and had begun to make inroads in the English-speaking world through translated covers. It took four increasingly ambitious solo albums (plus the companion album to his BBC TV show, of which no footage survives) for Walker to release an LP of completely original material: 1969’s Scott 4, a stone-cold masterpiece that also turned out to be a commercial failure. Fascinated by totalitarianism, death, prostitution, the trauma of war, and general all-around seediness, the songwriter’s mature work has its roots in his Brel interpretations, which gave him his first opportunities to play with taboo subjects and language. (Walker’s first solo single, the Brel cover “Jackie,” was banned from airplay by the BBC, but still charted and made Scott 2 into an unlikely No. 1 hit.)

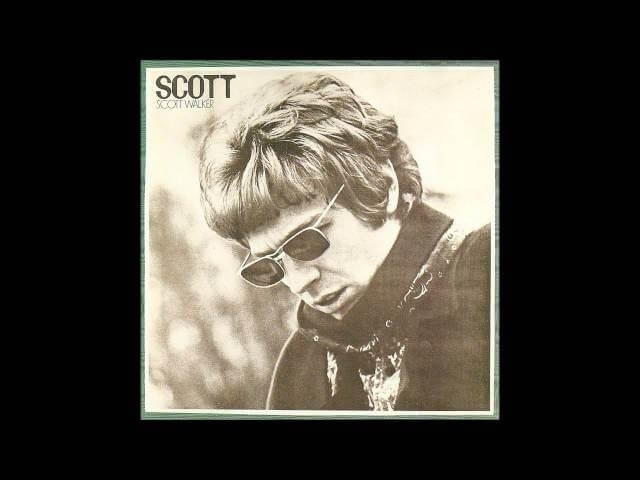

There are three Brel covers on Walker’s first solo album, Scott, one of which he downright owns. That song is “My Death,” an interpretation of Brel’s “La Mort” that sounds like a drowned body bobbing in a fogged-up harbor at night, with tremolo guitar and spider-like harpsichord moving over a lush, doomed backdrop of horns and strings. The other Brel songs on Scott—including the album-closing rendition of “Amsterdam,” one of the Brel’s greatest songs—are good, but they still constitute not much more than rousing, faithful performances of someone else’s material. “My Death,” however, is in a completely different landscape—a strange, morbid sonic world. Walker might not have written it, but it’s still one of his great songs, a foreboding shiver of lush pop that represents the moment where his sensibility as an album artist began to mature, and the start of a line that can be traced all the way to “Patriot (A Single)” and beyond.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.