A French master found droll comedy in one of the earliest King Arthur stories

Watch This offers movie recommendations inspired by new releases, premieres, current events, or occasionally just our own inscrutable whims. This week: David Lowery’s The Green Knight, starring Dev Patel as King Arthur’s nephew Gawain, has been postponed. But there are plenty of other interesting takes on the Arthurian legends available to stream from home today.

Perceval Le Gallois (1978)

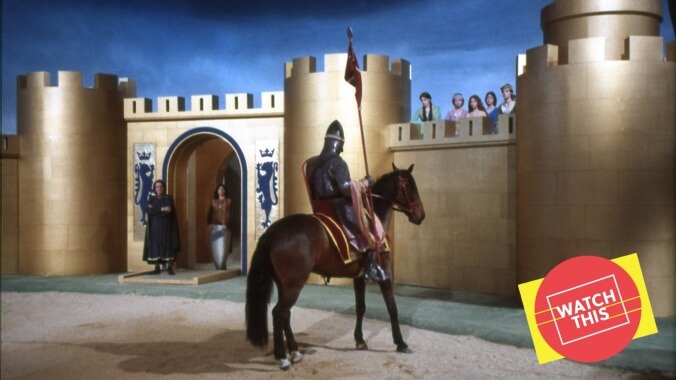

Éric Rohmer’s Perceval Le Gallois, a wonderfully eccentric de-interpretation of Arthurian romance, is in every respect an oddity among King Arthur movies. The anachronism of cinema aside, there is not much in the film that post-dates the 12th century, when Chrétien de Troyes’ verse romance “Perceval, The Story Of The Grail” was composed. The sets have no sense of perspective and unreal proportions of the kind found in the illustrations of illuminated manuscripts. The castles are not much taller than the actors, and the colors and costumes are simplistic. The cast, led by a fresh-faced Fabrice Luchini as the title character, appears to be centuries removed from dramatic convention; the actors narrate their own actions in the third person and strike the kind of contorted poses seen in medieval miniatures, with palms open and their elbows at their sides.

Even the story represents an earlier iteration of Arthurian legend than we’re used to. “Perceval, The Story Of The Grail” was written almost three centuries before Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (the main source material for King Arthur stories since the waning of the Middle Ages) and mere decades after the completion of Geoffrey Of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, which first popularized the Welsh myth of Arthur and his knights. It is the earliest Arthurian romance to mention the Grail (not yet holy and described as a bowl) and the Fisher King, and recounts the origins of the knight who would later become known as Percival, Percivale, or Parzifal—a story that Chrétien never finished.

It’s worth noting here that the centuries-long process by which Arthurian legend transformed from pseudo-history into literature (the closest modern analog to which is something like fan fiction) was the work of both mass imagination and individual artistry, in which Chrétien played the first crucial role. His passing mention of a place called Camelot grew into an entire mythos; his introduction of a mysteriously significant object called the Grail was developed by generations of poets into the central quest of the Arthurian canon. It’s possible that he invented the character of Lancelot.

Perceval Le Gallois takes these long-reworked inspirations back to their beginnings. Rohmer’s script preserves the ambiguities, idiosyncrasies, and humor of the text, which breaks off from the story of the heroic simpleton Perceval before he learns the true meaning of the Grail to instead regale the reader with a long (and similarly unfinished) tale about Sir Gawain (André Dussollier). But however scholarly, Perceval Le Gallois is neither purely educational nor impersonal.

Chrétien’s verse already features plenty of comedy, and the fact that Rohmer’s adaptation plays up a droll sense of humor is almost inevitable—because before Perceval was transformed into an embodiment of purity and piety, he was a medieval redneck joke. In Perceval, he is a gawping bumpkin who was raised with chivalric ideals by his mother but mistakes knights for angels and forces himself on the first woman he sees due to a misinterpretation of the concept of courtly love. Against the flat backdrops, even the abruptness of the violence takes on comic qualities.

It would only be partly accurate to say that all of this represents an extreme outlier in a career largely devoted to the personal lives of talkative Parisians. There was, in fact, always something medieval about Rohmer, who preferred to make movies in themed series and was fascinated with morals, proverbs, and changing seasons. And that’s not to mention that, like many a medieval author, he was a devout Catholic who left few clues as to his biography. (The man born either Maurice or Jean-Marie Schérer was so successful at guarding his privacy, going so far as to give conflicting information to reporters, that his mother died without ever knowing that her son was a highly regarded film director.)

Perceval is, in this sense, another Rohmer movie about a callow young man, who is not unlike the male protagonists of the director’s earlier “Six Moral Tales” cycle—which included his breakthrough film, My Night At Maud’s—in that one isn’t completely sure that he’s learned the lesson he’s been taught. The enigmatic ending, into which Rohmer interpolates a medieval passion play with Luchini as Jesus, identifies Perceval with holy fools and Christian pilgrims (which may have been obvious to a medieval reader) without dispelling a sense of mystery. We may have spent two hours and change in the world of the medieval imagination, filled with chainmail, sick kings, transorbital impalements, and religious symbolism, but it’s a world we can only glimpse in incomplete pieces.

Availability: Perceval Le Gallois is available to rent digitally from Amazon. It’s also currently streaming on TUBI for free with minimal ad breaks.