A Gifted Man: “In Case Of Discomfort”

Whatever happened to political television dramas?

I don’t mean dramas set in the world of politics. Those obviously died because a million different writers tried to be Aaron Sorkin in the wake of The West Wing’s success and failed. What I mean are television dramas informed by the issues and politics of the day. They were a dime a dozen in the ‘80s and ‘90s, with shows as wide-ranging as Cagney & Lacey, with its ultra-serious takes on feminism and police unions and every hot-button issue of the time, and L.A. Law, with its ultra-quirky spin on just about every single thing going on in the country in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, offering up places for viewers to consider what was happening in the country around them. Nowadays, outside of a David E. Kelley drama here or there (where the writer’s politics become uncomfortable harangues to sit through, even if you largely agree with them), there just aren’t shows trying to seriously consider these sorts of things. The Wire was, of course, very political, but it was also watched by practically no one in its initial airing. (This may be why more dramas don’t do politics.)

This doesn’t mean all TV drama is apolitical. Breaking Bad is interested in how the recession has affected the American family and the American male as breadwinner. The Good Wife examines what it takes to get ahead in the world of politics and the law and the corrupting influences of money on both. Even a show as seemingly warm and fuzzy as Parenthood is very interested in how class distinctions in the U.S. manifest themselves through four otherwise similar siblings. And there’s something to be said for tackling these issues obliquely, instead of having every episode stop point-blank to have Walter White talk at length about how the recession is a terrible thing and how it’s created an American malaise or what have you. But at the same time, it often seems as if too many TV dramas take place in a reality completely divorced from our own, where there is no economic crisis, where people never discuss serious political issues, and where the only thing anybody cares about is getting the job done.

I mention all of this because there are some fairly potent political ideas at the center of A Gifted Man, but the show mostly shoves them aside in favor of dramatic bullshit and feel-goodery. There’s nothing wrong with the latter. I like a little sap in my weekend meal plan. The former, of course, is more of a problem, which we’ll get to. But the biggest thing that’s frustrating me about this show is that it has the potential to be something more. It has the potential to be a show about the health care system in the U.S., beyond just the cursory suggestion that some people can afford health care, and some people can’t. It has the potential to be an intriguing show about the philosophy of morality—I loved the scene where Anna suggested that being good isn’t just not being bad tonight. Forcing yourself to do good things is actively different from not doing bad things, and I think there’s a show in that idea. Hell, there’s probably a good show in here about spirituality, and the different approaches different people have toward the idea of “healing.”

The problem is that these things are only getting lip service. I hang on to the health care stuff because it’s the thing that’s closest to working, the thing that would be easiest to fix. But the show tiptoes right up to talking about how health care distribution is unequal in this country without really getting into it. I’m not saying the show has to condemn or condone this. I’m not even saying it needs to do all that much more beyond just say, “Hey, this is happening. What do you think?” But when the show seems to take place in a world where, say, both the clinic Michael spends most of his time at and the free clinic are more quirky TV settings than anything else, something gets lost. There’s a scene tonight where Michael sends one of his free-clinic patients to the “best” cardiologist in New York, and the guy’s wife weeps about how they’ll figure out a way to make it work. But there’s no real meat to this scene. It’s just a thing that happens, not really a scene where we see two people having to confront the fact that for one of them to live will require, essentially, submarining their entire lives. It’s not really clear how much Michael realizes this either. On the one hand, I like the idea of Michael sending all of these free clinic clients to his doctor buddies all over town; on the other hand, it seems completely divorced from a reality where plenty of doctors do free clinic work every once in a while to give back as they can and where people like this man almost certainly couldn’t afford that level of care.

In general, this episode was better than last week’s (though not on the level of the pilot), but it still didn’t overcome the central dramatic problem of the show: If Michael is going to work at Anna’s old clinic and his regular offices, then the show needs to stop doing stories where the two patients of the week are balanced off of each other. There’s even the suggestion this week that Michael can’t save both, before he inevitably does. (The pilot got around this by having one of his patients die, but it’s not something that the show can realistically do on a weekly basis.) Sure, it was fun to see Mad Men’s Dr. Faye turn up as a pilot with a worm in her brain (ew!), and I liked some of the scenes and discussions. There were also more laughs to be had this week, particularly from the delightful Margo Martindale.

But there’s still the fact that A Gifted Man doesn’t really seem to share our reality, a fact that goes beyond the idea that it has a ghost (one that the show is clumsily trying to attach something like a “mythology” to). For a show like this to have teeth, it needs to have specificity. It needs to seemingly take place in a version of our world or one close enough that we can examine the similarities and differences. Instead, the show seems to take place in a neutered version of our world, where everything works out because Michael Holt is the kind of guy everybody talks about in hushed tones of reverence. (The restatement of the pilot’s plot and the way that Michael’s character is developed by everybody talking about him, rather than through action, both get fairly ridiculous tonight.) A Gifted Man has the chance to do some interesting—maybe even daring—things, but it refuses to really commit to any of its most fascinating ideas. Maybe A Gifted Man will never match its pilot’s tone, but there’s another show—perhaps an even more durable one—lurking within the program. Here’s hoping the writers find it in time.

Stray observations:

- Jennifer Ehle’s role in the show seems to have gotten lost entirely. She pops up in every episode, yes, but she’s mostly here to restate the pilot and have bizarre conflicts with Michael that don’t make a lot of sense. My favorite part here was when she compared Michael’s dislike of uncertainty to how she felt about being dead. Clang!

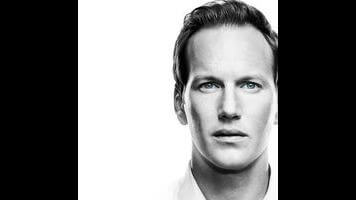

- On the other hand, I liked the scene at the basketball court, prompted by the ball landing on Michael’s car. I’m not sure I like the idea that there’s some “grand purpose” to all of this, but at least that was a scene that gave both Patrick Wilson and Jennifer Ehle something to sink their teeth into.

- This show is inevitably evolving to a point where Michael takes over the free clinic, isn’t it? If so, I’d almost rather see the show where he does that and copes with the ramifications of that decision on his life, sort of a big-city Everwood.

(Since no one’s going to read these reviews anyway, I may as well start burying excerpts from my never-to-be-published Frank Fisticuffs novel at the bottom of the stray observations. I mean, why not?)

The cold had grown unbearable, settling inside of him like an unwelcome house guest. He sat in the tent, shivering uncontrollably.

In the back of his head, he knew he was having the dream again. He tried to slap his dream self, tried to wake himself up.

He knew the next part. The tent opened. His mother’s face entered. She smiled briefly. And then the gunshot. They’d been found. They’d been caught.

He would be next if he didn’t move.

He awoke, staring at the ceiling, eyes open, sweat beading on his forehead. In the movies, they always sat straight up. He could never manage that after the dream. Always, always, he found himself pinned to the bed for at least a few minutes before he could woozily make his way to the bathroom, shake himself like a piñata.

Beside him, Margaret stirred. “Go to sleep,” he said. He’d long ago willed the tears from his eyes, and he was surprised to hear them present in his voice.

Drexler was just like the rest of them. He had to pay.