A great, experimental Doctor Who considers a world where all hope is gone

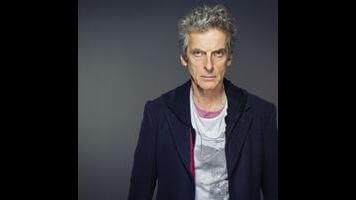

In each of Peter Capaldi’s three seasons aboard the TARDIS, Steven Moffat has for his Doctor an experimental, narrative-breaking episode. Season eight gave us “Listen,” in which it’s quite possible we witnessed a Time Lord’s mental breakdown. Season nine had “Heaven Sent,” which finds the Doctor almost entirely by himself and is probably my favorite new series episode. And now this year offers up “Extremis,” which pulls the rug out from under the audience in the most spectacular fashion. In fact, tonight’s story echoes quite a bit of “Heaven Sent,” though not in a way that feels repetitive, give or take the fact those monks have awfully similar claw-like hands to the confession-seeking Veil. Both “Heaven Sent” and “Extremis” reveal the Doctor we have spent most of the episode with isn’t exactly the Doctor, though the simulant of tonight’s episode represents a clearer break from the real thing than the endless chain of teleporter duplicates. Most importantly, both episodes consider the Doctor at the brink of death, forced to do what he knows what is right even when he knows this version of him can’t stand to benefit. Virtue is only virtue in extremis, after all.

I need to start close to the ending, because that’s the part that most lingers after watching this episode a couple times. Peter Capaldi is perilously close to becoming my unqualified pick for favorite Doctor, and the overriding reason is on display as he gently breaks it to Bill that neither of them nor anything else in this world is real. He underplays the moment, making small choices to signal both his compassion and his heartbreak. That approach grounds the impossibility of the moment, and it’s in this regard that Capaldi brings out the best in Steven Moffat. In retrospect, Matt Smith and the 11th Doctor brought out the most in Steven Moffat, with that actor and that character’s propensity for big, eccentric choices proving all too good a fit for Moffat’s love of the clever and convoluted. Capaldi’s restraint has focused those same instincts, giving us episodes like “Heaven Sent” and “Extremis.” The Doctor talks about ancient sects and their myths, how computers struggle with random numbers, and the unexpected sentience of Super Mario and other video game characters. It could all be ridiculous if it weren’t animated by the Doctor’s pain at what he now knows, by a simultaneous need to be honest with Bill and to be as kind as he can when he tells her the horrific truth.

Indeed, it’s worth noting how Bill’s presence also helps ground the episode’s otherwise out-there premise. “Extremis” doesn’t give Bill as much to do as some previous episodes, which is probably fair enough considering we only see the real Bill for a minute or so at the end there. But the Bill we do spend most of the episode with is an accurate simulacrum, and even the silliest, most comedic moments—like, say, the Pope wandering in on her date with a nervous, guilt-ridden Penny, a scene that shows restraint to the extent Penny isn’t actually wearing a cross around her neck—are connected to a lived-in person. Bill’s annoyance with the Doctor and all those interlopers from the Vatican is rooted in something authentic to the character we have gotten to know over the past few episodes. It’s also on display when she takes issue with Nardole ordering her to stay behind her. Bill needn’t be overtly defined by her being a woman or black or gay, but those traits cannot help but inform her character, and often that can mean fighting for her right to exist as an equal.

I’m not sure if it is pushing the connection too far to suggest that aspect also influences Bill’s demand to know what is real, though it wouldn’t shock me if that were an aspect of Pearl Mackie’s acting choice in that scene. The larger point though is that all of this consistently feels real when viewed through Bill’s eyes, and that wasn’t always the case with previous companions like Amy and Clara. The lack of artifice in Bill makes it all the more brutal when we realize that what we have been is nothing but artifice, that none of this is real. That extends to the guest actors in this episode, as both Corrado Invernizzi and Laurent Maurel impress with compelling turns as Cardinal Angelo and the CERN physicist Nicolas, respectively. The former is a particular standout, his mere presence signaling a foray into religion that Doctor Who rarely considers. Faith is treated as beside the point—the visitors from the Vatican have it, the Doctor doesn’t, let’s move on—but beyond that one barb about religion’s complexity the Doctor largely accepts the situation on its own merits. Invernizzi’s charismatic delivery makes the early barrage of exposition from Angelo more compelling, while his sincere offer of confession to the Doctor is a minor-key example of something “Extremis” excels at: It puts the Doctor in a position unlike any we’ve seen before.

The extended flashback sequences are also close to unprecedented as a storytelling device, especially as they transport us to the immediate aftermath of “The Husbands Of River Song.” After engaging with a bit of half-hearted misdirection about who is getting executed, the episode brings out Missy. I mentioned back in my review of “The Witch’s Familiar” that that two-parter succeeded in making both her and Davros capable of functioning as ongoing threats, rather than adversaries so epic in scale they would have to be permanently killed off after every appearance. “Extremis” represents payoff for that work, as the interactions between the Doctor and Missy here recall a more emotionally complex version of the repartee that Jon Pertwee’s Doctor and Roger Delgado’s Master had during their many encounters. Missy doesn’t have to convince the Doctor that she really is her friend, but it’s only at the moment of what she believes to be her death that the Doctor can consider she might, just might be capable of goodness. I don’t buy it for a second, but then the Doctor has always had a soft spot for the Master, regardless of whether he looked like Delgado or John Simm.

And anyway, the Doctor saving Missy says more about the Doctor than it does Missy. He does it because it’s the right thing, and a Doctor who doesn’t do the right thing is no Doctor at all. It’s a sweet touch that it’s River—albeit via Nardole, who has been officially licensed to kick the Doctor’s ass as necessary—who reminds him, with the blind, simulated Doctor clutching the diary close as heh recognizes his imminent non-existence is no reason to stop being the man he’s supposed to be. That takeaway is what binds past and present together in this episode, albeit a trace more subtly than most Doctor Who episodes do. It’s also what makes “Extremis” more than another Moffat puzzle box episode, as the story here is less about solving the latest conceptual mystery and more about reckoning with what it means to be the Doctor. Even then, it’s not in the abstracted, self-referential way that a lot of 11th Doctor episodes did, but rather the issue here is about facing up to the responsibility of being the Doctor, and recognizing that one’s imminent and inevitable death is no reason to abandon that responsibility.

“Extremis” is a work that rewards multiple viewings, but not quite in the way “Oxygen” does, where rewatching the episode can unspool details that were too compressed to notice the first time round. Rather, it’s plenty compelling to get lost in the mystery on a first watch, to focus on the emotion and thematic work on a second, and then to dig into all the little details and connections on a third. This is Steven Moffat at his best, because this is Peter Capaldi—and Pearl Mackie, and Matt Lucas, and Michelle Gomez, and most of the guest cast, and director Daniel Nettheim—at their best. Like “Listen” and especially like “Heaven Sent,” the result is unlike anything else you’re likely to find on television, and certainly unlike anything else Doctor Who has done before. And the actual story is still only getting started, but more on that next week…

Stray observations

- Indeed, I will wait to consider this until we get to the end of the arc, but I love the way Doctor Who is structuring this multi-episode storytelling. The Doctor’s blindness carries over from “Oxygen,” with the monks set to launch their attack proper next week. Each scenario is distinct enough that Doctor Who can do its customary reset between stories—that “Extremis” is about a simulation and so somewhat independent of overarching continuity helps—while still doing serialization more elegantly than most previous attempts.

- I’m a fan of how the show handled the Vault reveal, which is to say get it out of the way as early as possible and go with the most logical solution. I knew from an interview Moffat gave that the reveal was coming in this episode, and if it had been at all delayed I would have likely been distracted by the prospect of an early John Simm cameo. Better to keep the focus on the episode at hand than letting the mystery gobble everything up.

- I ended up not having a whole bunch to say about Matt Lucas and Michelle Gomez, but suffice it to say they are both excellent here. Gomez’s strong work in a small role is no surprise, while Lucas is really bringing out new dimensions to Nardole with each new episode. I’m not sure he’s the most shocking companion reclamation project from his goofy beginnings in “The Husbands Of River Song,” as Donna Noble probably still holds that honor, but it’s getting close.

- I cracked up every time Nardole had to cover for the Doctor’s blindness by describing what was in front of them. It’s also a hell of a useful gimmick if Big Finish can ever get Capaldi and Lucas in for some audio adventures.

- I mentioned him in passing, but serious credit to Daniel Nettheim for his work directing this episode. Everything to do with the Doctor’s blindness is especially well handled.