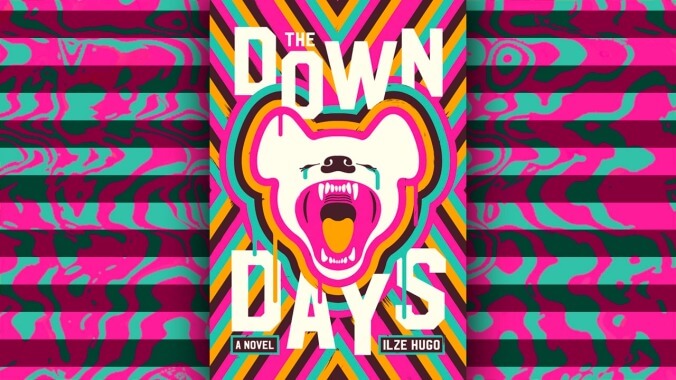

A hopeful pandemic novel? The Down Days finds beauty in an apocalyptic world

Early in Ilze Hugo’s debut novel The Down Days, a thief named Sans contemplates American apocalyptic films portraying “vicious viruses sweeping nations and the world coming to an end with a bang and a crash.” Living in a near-future vision of Hugo’s native Cape Town, South Africa, that has for seven years been ravaged by a deadly disease, Sans notes that fiction failed to predict his reality: “Things just kind of fizzled out slowly until the past felt like a hazy fairy tale that had happened to somebody else.”

The Down Days is one of the most accurate depictions of the strange realities of life during a pandemic. Hugo’s eerily prescient story depicts a world fundamentally transformed but still recognizable. Everyone wears masks and gloves in public, with elbow bumps replacing handshakes. The government has set up mandatory temperature checks. Someone taking a sick day creates way more unease than it once did. Conspiracy theories and talk of miracle cures abound. Cleaning products fly off shelves, and some people start drinking bleach.

While the rich were able to stay in isolation or flee the city, those without means do whatever they can to get by. Sans runs an elaborate scheme making weaves from hair cut during religious rituals, but winds up in trouble when he runs off with a mysterious woman with the hair of a unicorn. The narrative mostly follows him and Faith September, a taxi driver who now drives around the city collecting the bodies of plague victims and does pro bono work as a private investigator. Both become embroiled in a mystery involving missing kids, which requires them to enlist the help of a wide variety of quirky characters, including an underground data dealer, a sin-eater, and the writer of a conspiracy theory-packed newspaper who also makes money by getting beat up while dressed as the Easter bunny.

A shaggy dog story and modern noir, The Down Days feels particularly familiar now, due in part to its strange blend of tragedy and absurdity. The plague at the center of The Down Days starts with hysterical laughter, which has led to a ban on laughing in public. Yet the ban doesn’t strip the story of humor, with characters finding solace in baking, underground comedy clubs, and lip porn for those who miss the sight of a smiling face.

The Down Days recalls Ling Ma’s Severance in its critique of how the end of the world can’t stop the routines of modern life. But while so much apocalyptic fiction winds up dwelling on humanity’s worst impulses, Hugo’s novel is far more optimistic. There are no real villains here except for maybe the self-righteous and delusional who deny the plague’s power or claim to have a cure, like a group of evangelicals who believe that the disease can be prevented by cutting out processed foods. Mostly it’s a story of flawed people, each broken in some way by grief and the fundamental shift in how society functions. Even the people who do the worst things are sympathetic; they’re just trying to survive and help others through an impossible situation.

Hugo’s strange version of Cape Town, rechristened Sick City, is vibrantly brought to life through her detailed descriptions. Punctuated with Afrikaans expressions, local slang, and Zulu mythology, The Down Days contains asides about South Africa’s history of colonialism, slavery, and corruption without preaching. In fact, it’s a surprisingly breezy novel with short chapters that jump between perspectives as the narrative moves with the bustle of city life, all of the action condensed over the course of just a few days.

The result closely resembles Sam J. Miller’s Blackfish City, highly literary speculative fiction that blends elements of sci-fi and mysticism but grounds the high concepts with charming characters and a brilliantly realized setting. There are also echoes of Peng Shepherd’s The Book Of M in that Hugo is more interested in setting up a metaphor and creating a mood than providing answers to all of her mysteries.

While that choice may make the book’s ending somewhat unsatisfying, it’s still a surprisingly comforting work. The Down Days isn’t a post-apocalyptic plague tale about surviving the end of the world or rebuilding something from the ashes; it’s a story about how nothing ever really ends. Hugo notes that South Africa has endured smallpox, the bubonic plague, and AIDS, and while each outbreak was devastating, they eventually became part of history. The world may be dramatically changed, but when people are willing to take risks and work together, we can get through anything.