A Jackie Chan-John Cusack pairing should be more fun than Dragon Blade

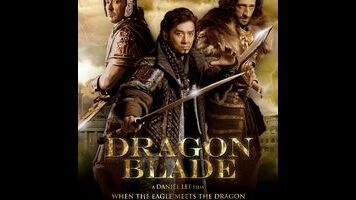

In Dragon Blade—a Chinese blockbuster that’s now making its way here, short about 25 minutes of running time—a Roman legion finds itself on the eastern stretch of the Silk Road, joining forces with a Han Dynasty outpost to fend off a foe from back home. The result is part hokey peplum movie, part typically overscaled Mainland production, boosted by the novelty factor of watching the now 61-year-old Jackie Chan bust a few limber moves while John Cusack and Adrien Brody glare at each other as rival Romans. A long way from his breakthrough, Black Mask, director Daniel Lee displays only glimmers of the cartoonish, gonzo sensibility that once made him seem like an interesting talent. In its place is strained seriousness and a butt-ugly digital palette of tan and sand.

Chan—given a goatee-sideburns-braids combination that screams “Christian nü-metal”—plays Huo An, a Han patrol commander who is framed for smuggling and sentenced to hard labor at a remote fortress called Wild Goose Gate. When a band of soldiers from the far West is sighted on the horizon, Huo An is re-promoted to defense, and finds himself, in rapid succession, squaring off with Roman commander Lucius (Cusack) in hand-to-hand combat, inviting him into the fortress to sit out an oncoming sandstorm, and then making friends with the Romans in order to use their knowledge of civil engineering to make necessary repairs. (Presumably, this is where most of the cuts came in for the American release, in order to barrel straight form the all-Mandarin first act into the English-heavy middle.)

Lee establishes a rudimentary buddy-hero dynamic, with Huo An as the chummy local who’s spent his career trying to keep the peace between dozens of warring tribes, and Lucius as the poker-faced foreigner who only knows how to maneuver and conquer. Cusack is surprisingly effective, and Brody—cast as a loony big bad named Tiberius—acquits himself in what’s essentially a ham role. (Oddly, both parts feel like they were written for Nicolas Cage.) The rest of the English-language cast, however, is absolutely atrocious, and any time a legionnaire enters frame with bad news, the viewer is plunged into an alternate dimension where movie stars are forced to act in a Guffmanesque community theater production of Gladiator.

Though Lee has made a name for himself as a director of expensive historical fantasies (White Vengeance, Three Kingdoms: Resurrection Of The Dragon), the best moments in his work are still the ones that recall his roots in the energetic Hong Kong industry of the 1990s. For all of its swooping CGI landscapes—the matte paintings of the modern age—and its massed armies on horseback, Dragon Blade only develops momentum when it gets small, whether in close-quarters martial arts combat or through glints of broad physical comedy. (Huo An trying to avoid touching a female tribal chieftain’s breasts during a fight comes to mind.)

While the movie’s severe color grading—in which even Huo An’s nominally blue uniform appears to be a shade of brown—sometimes undercuts the impression of movement by making every object more or less the same color, there’s still plenty of peppy camerawork in the movie’s fight scenes, done in the lively, wide-angle lens style closely identified with Hong Kong’s genre-movie tradition. The problem is that little of it fits together, and one would be hard-pressed to put all the blame for the movie’s awkward structural and editorial decisions on a botched Americanization. Whether it’s introducing random flashes of white screen or slowing down shots to a stuttered chop, Dragon Blade seems to be going out of its way to make sure the action never rises above the level of “watchable enough.”