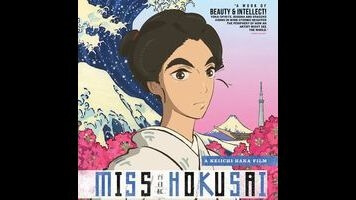

A Japanese artist gets an offbeat animated biopic in Miss Hokusai

It’s difficult at first to reckon with the jarring opening minutes of Miss Hokusai, Keiichi Hara’s anime adaptation of the Hinako Sugiura manga series. Named for the daughter of famed Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, the film starts with with O-Ei Hokusai narrating a brief scene illustrating her father’s manic creativity. She recalls how he’d dazzle his patrons with paintings the size of a wall, and then would follow that up by spending days etching onto grains of rice, just on a whim. As O-Ei finishes her anecdote, the soundtrack fills with slashing hard rock. The animator’s “camera” pulls back from her striding confidently down the street to reveal a bustling seaside metropolis, then a caption: “Edo, Summer 1814.”

The sudden eruption of electric guitar is a relative anomaly in Miss Hokusai, happening only once more. But as the film plays out, the reasons for framing Japan’s past in the context of the modern day become clearer. Like Sugiura’s comic, this is an episodic movie, weaving vivid vignettes into a larger picture of life in what would later become Tokyo. Aside from the clothing and the vehicles, the portrait is bracingly contemporary. The Hokusais and their hangers-on have frank conversations about the madness of artists, the commercial demands of the trade, and even about how to project raw sexuality onto a canvas. Though the film is PG-13, it’s aimed at arthouse-adept adults and mature older teens. In its contemplation of changing times and stubborn visions, Miss Hokusai is like a hybrid of The Wind Rises and Mr. Turner.

As touched on in the opening minutes, Katsushika Hokusai lived long enough to produce work in a variety of styles and disciplines, from erotic sketches to intense woodblock landscapes. (His most famous piece, “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa,” remains a staple of gallery gift shops.) In Miss Hokusai, O-Ei serves as a headstrong assistant, confident that she can reproduce any of her father’s drawings, paintings, and prints, even though her life experiences have been largely limited to working in a studio and taking care of her blind younger sister O-Nao. Most of the sequences in Miss Hokusai aim to distinguish the differences between two artists. When Katsushika describes his inspiration, he tells a long fantastical story about his hands detaching from his body and stretching out around the world. O-Ei, meanwhile, mainly talks about technique, picked up through careful observation.

The “roaming hands” dream is one of Miss Hokusai’s most memorable set pieces, but it’s far from the only standout. Hara frequently turns Hokusai’s art into an animated, interactive experience, with the images moving around the characters as they reflect on where they came from and what they mean. Some of the these pictures spring directly from a fevered subconscious. But when the Hokusais visit a brothel to research nudity and sex—mainly for the naive O-Ei’s benefit—the emphasis is more on how passionate expression still demands training, to articulate the mood and moment properly. When O-Ei and O-Nao find themselves out on the sea, braving a roiling version of one of their father’s famous waves, it’s as though Katsushika’s world is right there with them always, just outside their front door, waiting for someone adept enough to capture it.

Miss Hokusai flags when it focuses on the sickly O-Nao, if only because detours into sentimental melodrama are nowhere near as original and visually splendid as scenes that deal with characters conjuring art from their heads and hands. One of the ways this film feels fresh and revisionist is that it doesn’t succumb to “great man”-ism, positioning a famous artist’s genius as singular. Katsushika has an uncommon talent for turning everything he sees and experiences into striking images. As depicted by Hara, he comes across as slobbish and socially disconnected, more attuned to his muse than to the mundane details of daily existence. But by spending so much time with its title character, Miss Hokusai suggests that there’s also an art to facilitating someone else’s work, and becoming a skilled craftsperson. This is how culture progressed, from the 19th century to the 21st: through astonishing feats of imagination, and the slow grind of physical labor.