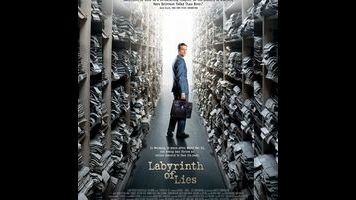

The German film Labyrinth Of Lies, a conservatively mounted period piece that opens in Frankfurt in 1958, portrays a society in which talking about the war is all but verboten. When reporter Thomas Gnielka (André Szymanski) barges into the local public prosecutor’s office, waving a piece of paper that accuses a local schoolteacher of having been a guard at Auschwitz, no one wants to have anything to do with it. Why threaten a hard-won stability by dredging these matters up—and what was Auschwitz anyway? This based-on-a-true-story film—directed by Giulio Ricciarelli, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Elizabeth Bartel—is no masterpiece, but it does a good job of conveying the varieties of German willful ignorance concerning the Holocaust nearly two decades after it took place. Junior prosecutor Johann Radmann (Alexander Fehling), a stickler for the letter of the law and as naïve as anyone of his generation as to the events of the war, nonetheless looks into the journalist’s complaint. Dogged further research, and critical support from attorney general Fritz Bauer (Gert Voss), sets him on the long road to the 1963-65 Auschwitz trials, which sent 17 of the camp’s rank-and-file to prison on murder-related charges.

Ricciarelli’s uneven movie works best when Johann is in the process of amassing material, struggling to get a handle on the shape of his investigation as he culls files from a U.S. Army archive and conducts exhaustive interviews with camp survivors. During these passages, the filmmaker shows his protagonist (a composite of two real-life figures) grappling fully with the daunting question of how to prosecute industrial killing, and Fehling successfully conveys the sense of a man steeling himself against the ugly truth that’s developing before his eyes, and preparing for a long fight against the blind-eye policies of a public sector flush with former Nazis. His sense of responsibility to the victims has long since been established. Early on, Johann falls in with Thomas’ bohemian social circle, not only swooning for a dressmaker (Friederike Becht) but also befriending an alcoholic painter (affectingly played with furrowed brows by Revanche’s Johannes Krisch) who lost his twin daughters at Auschwitz.

Labyrinth Of Lies, which Germany has elected to be its horse in the race for next year’s foreign-language Oscar, is a lot more thought-provoking on issues of collective memory (or lack thereof) than the typical prestige picture, but it does falter dramatically in its later stretches. The film struggles to locate an appropriate through-line from within the mountain of explosive potential evidence on Johann’s desk. The prosecutor’s eventual obsession with capturing Nazi torturer Josef Mengele feels less like an obsessive crusade than a manhunt manufactured to generate a little pick-me-up suspense. Not enough time is devoted to Johann’s family history to make it suitably devastating when an inconvenient truth about that past finally comes to light. Somewhere along the way, Bauer informs his tireless subordinate, “This is a labyrinth. Don’t get lost in it.” Ricciarelli himself doesn’t seem to have followed this sage advice, but he should get credit for following his protagonist as deep into the mire of accountability as he does.