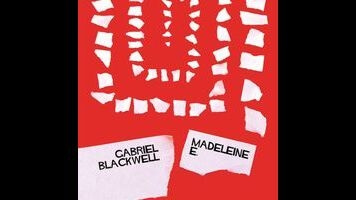

Insights ebb and flow throughout Madeleine E., named for the woman that Kim Novak’s character pretends to be in the film, as the author considers themes like identity, artificial intelligence, Freud’s theory of the uncanny, and the slipperiness of truth. This happens through not only his critical analysis and chosen excerpts (from such authors as Robin Wood, Rebecca Solnit, and W.G. Sebald—fans of the latter will be at home here) but also his nonfictional and fictional passages, in which he often demonstrates obsessive qualities similar to Stewart’s character. In one section, Blackwell sees his doppelgänger in San Francisco (not for nothing, Vertigo’s setting); in another, he considers following his wife after seeing her far from work in the middle of the day.

What’s most interesting about the fictional sections is that they at first disguise themselves as nonfiction, so similar are they to what the author has presented as fact, throwing into question the memoir that came before. This might frustrate readers who want a clear delineation between fact and fiction, but one argument the book offers, like Vertigo, is the near impossibility of determining what is and is not true, what is and is not artifice, persona, or acting. The answer is that it is all both true and false, as one’s perception frequently holds the most weight.

Some of the fictional sections feel extraneous, however, as the book runs long. The momentum slows halfway through, as Blackwell adds more and more examples of doubles and mistaken identity. Occasionally he seems to ignore the most logical explanations for things, as that would deflate their potential for intrigue. This imbues Madeleine E. with a layered logic similar to that of an M.C. Escher drawing or Synecdoche, New York, growing larger and more complex as it circles back on itself.

The book shares two of its strengths with the movie it’s based on: its tone and its theme of obsessive looking. Despite the book’s multiple voices, Blackwell maintains a melancholy and ruminative mood throughout. More important is his perspicacious eye. Like Scottie’s obsession over “Madeleine,” Blackwell has a keen perception, yet, unlike Scottie, he is aware of his male gaze and obsession. (Those who’ve seen the film at least a few times will get the most out of this book.) In a beautiful passage near the end, Blackwell describes one of the most self-aware ideas at the heart of his observations: “[W]hen we see something seemingly everywhere, it doesn’t mean that the thing we think we are seeing again and again has multiplied somehow or that the world is a code or a conspiracy, but that, in finally taking notice of that thing, we are creating for ourselves a new way of seeing…” This doesn’t result in a lean, driven book, but it does present an intelligent, personal meditation on one of the greatest films of all time.