A Marvelous Life doesn’t sugarcoat the enthralling origin story of Stan Lee

He plays a juror in the made-for-TV film The Trial Of The Incredible Hulk (1989) and a hot dog vendor in the original X-Men (2000). In Spider-Man (2002) and Spider-Man 2 (2004), he appears as a bystander who rescues others from falling debris. In Daredevil (2003), a young Matt Murdock in turn saves his life. His cinematic cameos, numbering in the dozens, are goofy, Easter-eggy, insidery: a mailman in Fantastic Four (2005), a mental patient in Thor: The Dark World (2013), a strip club emcee in Deadpool (2016). In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, he is omnipresent: oversized glasses, gray mustache, thinning hair, that familiar smile. But the greatest role Stanley Lieber ever played was Stan Lee, the most famous, and arguably greatest, comic book creator who ever lived.

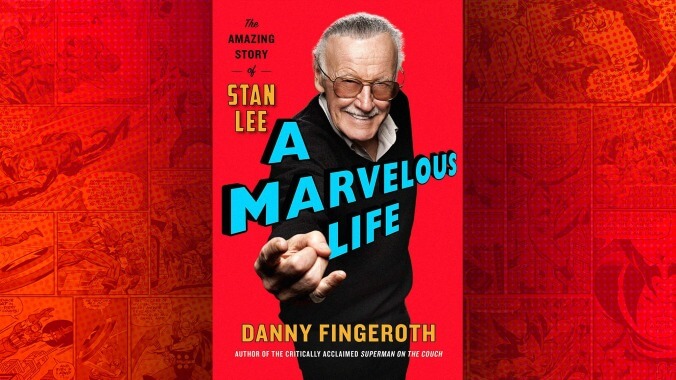

Lieber’s origin story is as good as any of the characters he would go on to create, and Danny Fingeroth’s new biography, A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story Of Stan Lee, tells it well. Born to Romanian-Jewish immigrant parents in 1922, Stanley Martin Lieber wanted to be the American Shakespeare, whom he called a “complete writer” and “my god.” He graduated from high school in 1939, the same year his cousin by marriage Martin Goodman, a middling pulp magazine publisher, struck gold with the first issue of Marvel Comics. That series introduced the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner to a post-Depression public hungry for superheroes (Superman and Batman made their first appearances in the months prior).

Late the following year, the 17-year-old Lieber arrived at his cousin’s Manhattan office looking for work. His timing was, shall we say, prescient; Goodman’s Timely Comics line was about to introduce Captain America. While gophering for Cap’s co-creators, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, Lieber began penning short, filler pages. He’d byline those stories “Stan Lee,” opting to save his birth name for the Great American Novel he aspired to write.

In January 1942, at the age of 18, Lee became Timely’s unofficial editor-in-chief, a role that he would occupy, after official promotion, for the next three decades. People would soon start calling Timely “Stan Lee’s company.” He wrote prodigiously and expanded the number of titles to around 70 per month, adding humor, romance, mystery, and horror offerings, which eventually outpaced the superheroes. By decade’s end, at Goodman’s behest, Lee fired the majority of his staff and rehired most as freelancers. It was not the first time he would be accused of privileging management over the artistic talent.

Timely, renamed Atlas then Marvel, limped through the 1950s after canceling four-fifths of its line in response to anti-comics crusading moralists. Lee called this his “human pilot light” period, a time of stagnation, of waiting for a spark of inspiration. Enter the brilliant and innovative Jack Kirby, who foresaw a superhero renaissance. Credited to Lee and Kirby, The Fantastic Four #1 became an unheralded success in late 1961. Over the next two years, Lee co-created the pantheon of characters that centered what he deemed the “Marvel Age”: the Hulk, Thor, Ant-Man, Wasp, Iron Man, Sgt. Fury, Dr. Strange, Spider-Man, Daredevil, and the X-Men (Black Panther arrived a few years later).

But the man known for creating heroes often played a villainous role. Beginning early in his career, Lee diminished or outright erased the contributions of his collaborators. Writers imagine characters, Lee believed, and artists merely channel that genius into the comics medium. He wrote Simon out of Captain America’s origin story, publicly bickered for decades with Kirby over attributions, and, most notably, did his best to wrest Spider-Man from co-creator Steve Ditko. Facing criticism from comic fans, Lee eventually reconciled, but in the most halfhearted and often contradictory way. “I’m willing to say [Ditko’s] the co-creator [of Spider-Man],” Lee told one interviewer. “Although in my heart of hearts, I still feel that the guy who comes up with the original idea for something is the guy who created it.” The always blunt Kirby would not be swayed: “All of it was mine besides the words in the balloons.”

Although Fingeroth acknowledges Lee’s misdeeds, he sides with the Stan camp. “As much as anyone,” he writes, “Stan Lee helped create the popular culture of the 1960s.”

The second half of this nearly 400-page biography covers Lee’s far less fecund, and much less interesting, post-1960s career, which perhaps explains the copious and tiresome repetitions that mar Fingeroth’s otherwise entertaining book. After graduating to publisher and president of Marvel Comics in 1972, Lee wrote few stories beyond a syndicated Spider-Man comic strip, relocated to Hollywood, and grew old as an Excelsior!-spewing company hype man who succumbed to questionable money grabs (remember Stripperella and Stan Lee cologne?).

A Marvelous Life leaves readers with the ultimate What If scenario: What If Lee had kept on collaborating with Kirby and Ditko? In one of his final cinematic cameos, before his death in 2018, Lee appears in Guardians Of The Galaxy Vol. 2 as a Moon-marooned astronaut recounting his life to a disinterested group of Watchers, the Marvel Universe’s all-seeing, all-knowing extraterrestrial panopticons. “Hey, wait, where you going,” he shouts as the Watchers walk away, “I’ve got so many more stories to tell.”