A movie that pits Bruce Lee, Steve McQueen, and a Shaolin monk against gangsters shouldn't be as boring as Birth Of The Dragon

To understand the phenomenon of Bruce Lee, you have to go back to his first black-and-white screen test, done in 1965 for a Charlie Chan TV series that never got made. The set is an incongruous living room somewhere on the Fox lot, and Lee is dressed in a phenomenally tailored suit. He’s already disgustingly photogenic, but on top of that, he’s killing it. He carries himself like he’s the big guest on that night’s Johnny Carson. The producer asks him to show some kung-fu moves and bring out an assistant, who turns out to be this total midcentury dinosaur in horn-rimmed glasses. Lee is smiling and schmoozing and making the crew laugh off camera, but his movements at the guy are scarily fast.

This is pure Lee. He never went for anything better than second-rate material—inane plots, cartoon sound effects, punches that never exactly connect, cheesy zooms—but he strode through it unassailable and physically perfect, sweat glistening on his incredibly developed torso, redolent of a kind of beauty that hadn’t obsessed the camera since the start of the 20th century. Movies had mostly forgotten about muscles before Lee came along, and while the average Hollywood leading man now looks like a gym rat, nobody has matched Lee in looking as commanding from as many different angles. The man knew he was a work of art. Really believed it.

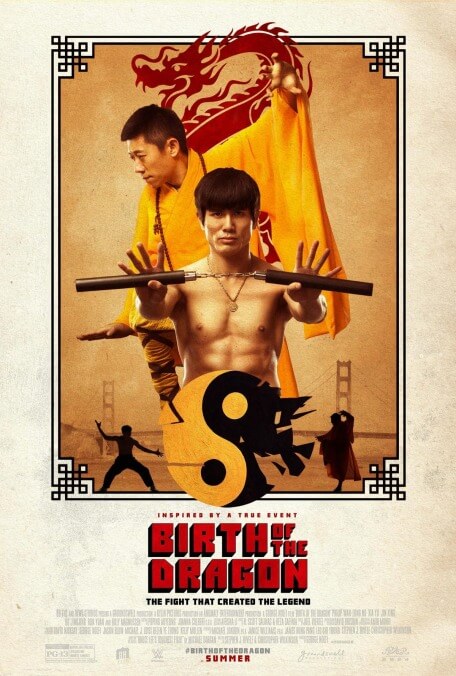

Maybe it’s because he was a genre in and of himself that Lee became the most counterfeited star since Charlie Chaplin, as countless knockoff cheapies followed his death, headlined by a slew of impostors who adopted such names as Bruce Li, Bruce Le, Bruce Lai, and Lee Bruce. (There was also the two-for-one special Bronson Lee, who wore a Death Wish haircut and mustache.) So take George Nolfi’s Birth Of The Dragon as an insipid modern update of the barrel-scraping Bruce-sploitation flick; there’s no reason a movie in which Bruce Lee and Steve McQueen (er, “Steve McKee”) duke it out with Chinatown gangsters in mid-1960s San Francisco has any business being this joyless and dull.

Birth Of The Dragon takes nominal inspiration from a notorious episode in Lee lore, his 1964 fight against the rival martial arts teacher Wong Jack Man—a touchy subject, as neither the fighters nor their witnesses ever agreed on even the most basic details of what happened or why. Yet a “he said, Lee said” Rashomon approach was apparently too obvious for Birth Of The Dragon. Instead, it reinvents Wong (Xia Yu) as a gnomic Shaolin monk who comes to San Francisco in the generic, “cue ‘Green Onions’” pre-hippie ’60s as an act of penance and is immediately perceived as a threat by the cocksure, 24-year-old, rock-star-guru-like Lee (the stiff, uncharismatic, 40-year-old Philip Ng).

It could’ve been worse, though it could’ve been a lot better, too. Xia, a mainland Chinese actor who first drew attention for starring in Jiang Wen’s superb debut, In The Heat Of The Sun, is a winning presence, and it’s easy to imagine the movie’s boastful Lee—who comes across as a total tool—self-destructively obsessing over the arrival of this martial-arts master who contents himself with living in a crappy SRO hotel and doing dishes in a local diner. But this isn’t some existential pop culture fable about rivalry and pride. No, its internal turmoil is all with “McKee” (Billy Magnussen, almost as bad as Ng), Lee’s short-tempered, motorcycle-riding star pupil; slowly drawn to Wong’s simpler wisdom, he eventually talks the two masters into facing off in a warehouse showdown.

Why? So he can free the pretty Xiulan (Qu Jingjing) from the clutches of the nefarious Auntie Blossom (Jin Xing, more or less reprising her role from the Tony Jaa vehicle The Protector, which is baffling) and stick it to the local tongs. Thus, Birth Of The Dragon finds itself in the saddest category of genre programmers—the kind whose conceptual craziness is canceled out by execution. The script (by Stephen J. Rivele and Christopher Wilkinson) is addicted to narrative banalities, killing time with subplots involving a local laundry business. The aura of cheap-o emptiness is overwhelming: Scenes tend to be visually featureless, composed against strangely empty walls or Vancouver street corners. Even the occasionally decent fight choreography looks unappealing. Nolfi, who previously wrote and directed The Adjustment Bureau, limits any assertions of artistic personality to making sure that the characters are seen wearing fedoras whenever possible.