“What if it’s a prank?” So asks Behnaz Jafari, the famous Iranian actress, in the opening minutes of 3 Faces. Jafari, who’s playing herself, is in the passenger seat of a car, hunched over a cell phone, her face illuminated by its glow. She’s watching what appears to be the video equivalent of a suicide letter that’s been addressed to her specifically. On it, a teenage girl (Marziyeh Rezaei)—her own face squashed into the vertical frame of a selfie— is so distraught over her family’s refusal to allow her to pursue an acting career that she hangs herself on camera. Or does she? “The branch looks too thin to support her weight,” Jafari says aloud. She doesn’t entirely believe the footage. Or maybe she just doesn’t want to. Is it a sick joke? A stunt? Some kind of warped version of an audition tape?

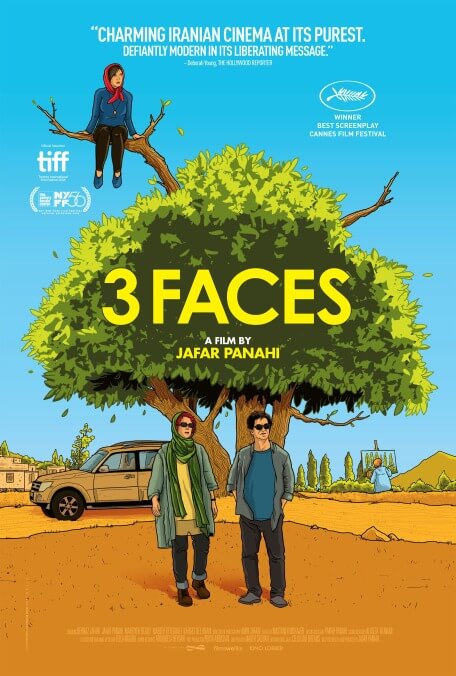

The star is right to wonder. She is, after all, appearing in the latest slippery drama from Jafar Panahi, the irrepressible (and unsuccessfully censored) Iranian director of This Is Not A Film and The Circle. Since his arrest in 2010 on charges of anti-government propaganda, Panahi has made movies—clandestinely shot and then smuggled out of Iran—that have blurred the line between fiction and reality. 3 Faces, which isn’t a documentary but does find Panahi once again appearing as himself, actually builds the search for that line into the work. It flirts, too, with a playful self-critique: Is there something manipulative about staging fiction to look like nonfiction?

That’s a question implicitly raised a couple times by Jafari, whose “character” begins to suspect the director may be in on the ruse once the two trek out to the supposedly dead girl’s village in the rural northwest of Iran, armed as usual with a camera Panahi isn’t supposed to be operating. And yet that element of urgency turns out to be something of a bait-and-switch. Defusing its dramatic stakes quicker than you might want, 3 Faces is ultimately less a mystery than another of the filmmaker’s ambling, episodic examinations of life in modern Iran. The faces of the title belong to three generations of actresses, once, current, and aspiring, all stifled in different ways by their culture’s gendered double standards. The film, of course, opens with two of these faces, cutting from the teen’s tear-soaked visage to that of the star she’s trying to reach. The third, that of a singer and dancer who was famous before the Revolution but now lives in total solitude, we never see. Her absence speaks volumes.

This is by far the least constricted of the director’s post-arrest films, most of which make their limitations the subject. (This Is Not A Film just wouldn’t work as a title for it.) Panahi, who’s now being allowed to travel some around the country, again adopts the persona of a benevolently befuddled visitor, wandering into significant conversations with the locals and encountering the occasional oversized metaphor, like an injured bull—celebrated for its virility—that’s literally blocking the path out of town. As in his last film, the more freewheeling Taxi, Panahi is also paying clear tribute to his old friend, countryman, and creative collaborator, the late Abbas Kiarostami. One can see that director’s influence on shots of cars winding around narrow, dusty roads, in a scene of an old woman lying in a ditch she’s dug for herself, and in some of Panahi’s more elegant shots, like one of his travelmate exiting and circling the vehicle, moving away from and then back towards the camera as it pivots within the car.

Kiarostami, to be honest, might have chased the real/not real question into knottier, more thought-provoking territory. Panahi’s work isn’t generally as conceptually radical—he’s more of an inquisitive humanist, bending the rules of his medium to get at truths about human nature. What’s heartening about the gentle, meditative 3 Faces is the way it continues to expand (or rather re-expand) not just the director’s radius of movement—how far he can drift from the home that was briefly his prison—but also the scope of his empathetic gaze. If the first couple films of his post-arrest period were understandably preoccupied with what it means to be an artist forbidden from making art, here Panahi has looked further past his own predicament, to the territory of his jubilantly feminist masterpiece, Offside. For as often as he appears on screen, he also recedes a bit into the background. Pointedly, the film is not called 4 Faces.