Book cover image: Seal Press Graphic: Natalie Peeples

The 1964 children’s novel Harriet The Spy inspired an entire generation of future writers and diarists. The protagonist—an Upper East Side 11-year-old who spies on her neighbors when she’s not spending time with her stern, knowledgeable nanny, Ole Golly—stood out from the idyllic young heroes and heroines of children’s literature of the era. Harriet was opinionated, sneaky, and stubborn, and rebelled against her parents’ demands. “I’ll be damned if I go!” she says of attending dance school.

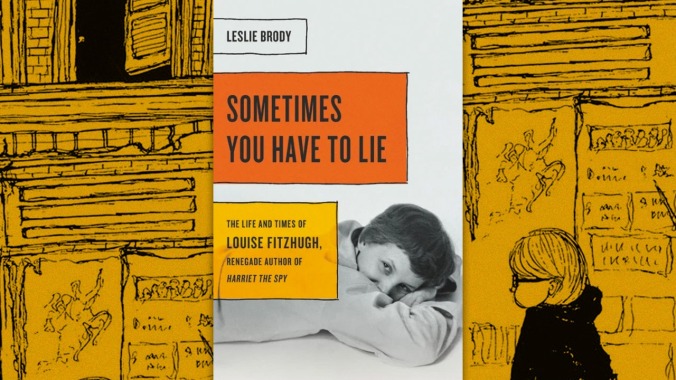

It turns out many of the roots of Harriet’s privileged existence can be found in the life of her creator, Louise Fitzhugh. Leslie Brody’s new biography, Sometimes You Have To Lie (a piece of Ole Golly dialogue), delves deep into the writer’s fascinating past. Fitzhugh was the product of a short-lived, tempestuous union between Millsaps Fitzhugh and Mary Louise Perkins, which started via a shipboard romance during the Roaring ’20s. The two soon realized they were ill-suited for each other, resulting in a fierce custody battle of baby Louise. Mary Louise had no chance against the well-off and established Fitzhugh family (Millsaps was a prominent Memphis lawyer), and as a result did not see her daughter for several years. Like Harriet, Fitzhugh was mostly raised by nannies and other house staff.

The young Louise apparently suffered few ill effects from this unconventional upbringing, and certainly no damage to her self-esteem. From the earliest of ages, the petite, pretty Southerner was steadfast in her opinions, caring little for what others thought. In the mid-century South, despite a series of male suitors (including one annulled marriage when she was underage), Fitzhugh primarily dated women. Rebelling against the white-glove, bridge-playing society in which she’d grown up (and which she would reference in Harriet), Fitzhugh kept her hair short, wore men’s clothing, and made no secret of her sexuality at a time when few queer people could afford to do so. As she told one male date who came to pick her up for a dance, “I am not going to join those menstruating minstrels.”

No doubt, Fitzhugh’s financial stability made it easier for her to flout convention, and to escape her Southern upbringing. Brody enthusiastically describes Louise’s thrilling adventures on ocean liners to Europe, hanging out in Parisian cafés and painting in Bologna, before moving to Greenwich Village. There she cultivated a social circle that included like-minded artists, including children’s book author Maurice Sendak, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and future fellow YA author Marijane Meaker (known as M.E. Kerr), who remembers that Louise was “always herself, never in the closet.” Her girlfriends were similarly ambitious, like her first love, Amelia Brent, who wound up working at Time magazine; soap opera actress Constance Ford; and Alixe Gordon, who became a prominent casting director.

Brody performed detailed research via newspaper clippings, correspondence, and a variety of interviews, and her descriptions in Sometimes You Have To Lie can get downright granular. “They shopped for furnishings at antique stores and flea markets, bought a lot of flowering plants, and set a dozen avocado pits to germinate around the house,” Brody writes of Fitzhugh and Gordon’s cluttered apartment near Fourteenth Street. The author paints Fitzhugh as compassionate but someone who didn’t suffer fools, and who worked almost constantly, even though her initial creative output leaned more toward painting than writing.

The publication of Harriet The Spy, Fitzhugh’s most famous and successful work, changed the trajectory of her life. She was no longer financially dependent on the family she otherwise had little use for, though it also brought her fame, which she wasn’t much interested in, shunning the book tours and interviews that would usually accompany such a sensational release. Harriet The Spy was not only a huge hit with booksellers, children’s librarians, and middle-school readers all over the country; it’s now credited with helping to create an age of New Realism for children’s literature, paving the way for authors like Kerr, Paul Zindel, and Judy Blume to craft imperfect protagonists for younger readers. “I don’t think it was her love for children, particularly, nor her identification with them that made her such a natural writer,” Kerr said of Fitzhugh’s approach. “I think it was more her insistence that children were people, not to be talked down to, patronized, or treated as some special group. The notion that children were people was a rare one, in those days, in our field.”

The publication of Harriet is both climactic and anti-climactic in Sometimes You Have To Lie. Fitzhugh’s story grows somewhat sadder as she tries to top her greatest success—publishing the less-well-received quasi-sequel The Long Secret the following year, and releasing a too-graphic anti-war picture book in the Vietnam era. Brody doesn’t hide her disdain for Fitzhugh’s final partner, Lois Morehead, the most domestic of the writer’s lovers, who made a home for them in suburban Connecticut. Following Fitzhugh’s fatal brain aneurysm, at the age of 46, there was no discussion of her lesbianism at the memorial, which Morehead organized, in direct opposition to the open way the writer lived her life.

Brody makes the case that the life Fitzhugh was able to craft can be listed among her most impressive creations: devoted friends, one long-term romance after another, and the will to never compromise over who she was—neither regarding her sexuality nor anything else. It makes the biography’s title puzzling. The true heart of Fitzhugh’s life can be found in what Ole Golly says after that line: “But to yourself you must always tell the truth.” In Sometimes You Have To Lie, Brody shows that Louise Fitzhugh certainly did so, offering Harriet The Spy fans even more to admire.