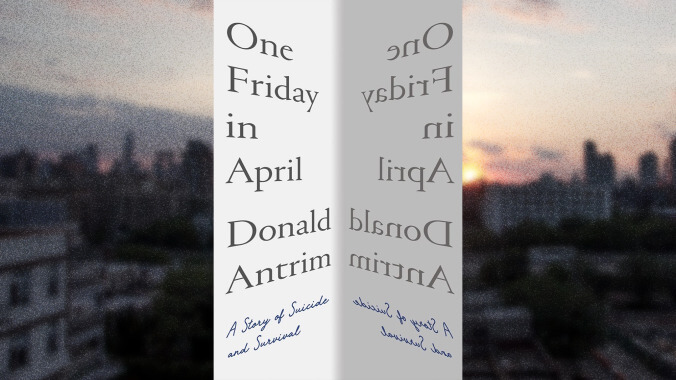

Cover image: Knopf Graphic: Allison Corr

On a spring afternoon in 2006, at the age of 47, the writer Donald Antrim climbed out on the roof of his Brooklyn apartment building, convinced that he would jump. One Friday In April: A Story Of Suicide And Survival is Antrim’s book about that day, the decades of treatment that preceded it, the long hospitalizations that followed, and the language with which we describe mental illness and despair. He doesn’t want to call his disease “depression,” meaning a downward slope, but simply “suicide,” the certainty of one’s death. Periods of despair and isolation come and go, but the ideation of death is constant; for Antrim, it seems that we have mixed up the symptom and the cause, the pattern and the act.

This raises inevitable questions: How does one treat suicide? Is there a cure? Perhaps unsurprisingly, Antrim identifies our choice of words as part of the problem. “Most of what we say about suicide has nothing to do with suicide,” he writes. He tells us that the terms themselves can impede our understanding of an illness, whether we are the patient, the doctor, or the friend who wants to help. Depictions of suicide attempts as either impulsive acts or rational responses obscure “the hours, months, and years of anxiety and physical deterioration, the fear and the seeming resignation with which we go to our deaths.”

As a fiction writer, Antrim is best known for his three novels, Elect Mr. Robinson For A Better World, The Hundred Brothers, and The Verificationist, all published before 2001. In the generation of young American post-modernists that emerged in the ’90s, he stood apart for being more conspicuously influenced by the likes of Donald Barthelme than chroniclers of system-wide paranoia like Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon. One finds, in his novels, absurdity, strange families, man-children, old houses, unusual forms of psychoanalysis, capital-I Institutes, and a fair amount of madness.

There is an Institute in One Friday In April as well, a place where Antrim undergoes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). At the time of the suicide attempt, Antrim had recently completed The Afterlife, an acclaimed memoir about his difficult relationship with his alcoholic mother; it was published while he was in the hospital. One Friday In April could, in some ways, be read as a companion piece, similarly sleepless, non-chronological, and ruminative. But the language here is starker, less evocative, sometimes even clinical.

He catalogs the many synonyms for melancholia and the physical side effects of both depression and the numerous medications used to treat it. Anyone who’s ever been there will feel an uncomfortable tinge of recognition, his descriptions of the strangely soothing life of the psych ward—the common rooms, the confiscated shoelaces, the meds, the routines, the visits from friends—and the out-of-the-cocoon feeling of clarity and euphoria that comes after one’s first trip inside, followed, inevitably, by the crushing realization that one has not been “cured.”

Antrim doesn’t present his story as unique, or even as much of a story, and he’s probably right to do so. The trade-off is that, despite its brevity (135 pages without the back matter), One Friday In April occasionally makes for monotonous reading, a succession of failed relationships and doctors, nurses, and therapists referred to by single initials: P, M, D, and so on. Friends come and go; relationships end; Antrim’s contemporary, David Foster Wallace, later to become the most mythologized of modern literary suicides, makes a cameo appearance.

In between, Antrim wonders about our metaphors for mental illness, the multiple meanings of “asylum,” the usefulness (or lack thereof) of such terms as “breakdown” and “reboot.” “Each era sees the world in terms of its own technologies,” he tells us. Freud “invokes the coal furnaces, steam engines, and valves and stoppers of the Industrial Revolution”; now we tend to think of our minds as computers. He briefly ponders the history of shock therapy and the stigma associated with ECT. He writes crisply of the sense of paralysis and eternity that accompanies depression. He recalls how he developed eczema on his forehead, “exactly where the mystical ‘third eye’ appears in religious iconography,” and then moves on to a brief description of the medial prefrontal cortex that lies underneath.

These kinds of paragraph-long micro-essays (i.e., the most writerly portions) are the best parts of One Friday In April. Antrim wants us to think of suicide not as the urge to die, but as a struggle to stay alive. “[I]f we accept that the suicide is trying to survive, then we can begin to describe an illness.” It is, admittedly, the kind of worldview a writer would want to believe: one in which we may be rescued by rhetoric and words about a disease that, above all, does not want to be discussed or written about. If there is a glimmer of realistic hope here, it’s in the simple fact that Antrim is describing events 15 or more years after the fact. He’s still around, now in his 60s, still suffering from anxiety and insomnia, but still around.

Author photo: Marija Ilic

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)