A phenomenal final season drags Brockmire, baseball, and America into a terrifying new future

For the past three seasons, Brockmire has used its title character to chronicle the final breaths of dying institutions. Series creator Joel Church Cooper depicts Jim Brockmire (expertly played by Hank Azaria) as a relic of the past living in a rapidly changing present: He’s an alcoholic baseball announcer trying to reclaim former professional glory and achieve some semblance of personal stability. Though he holds staunchly progressive values about everything from sex to class stratification, his personality was molded and developed by a culture that once enshrined hedonistic assholery as a point of pride. Brockmire’s antiquated sense of self functions as a working metaphor for baseball, America’s “national pastime” whose popularity has steadily declined over decades due to numerous contributing factors, such as its slow pace and a senescent fanbase. It doesn’t take much effort to extend this thread to America as a whole, a global superpower that has fallen prey to such debilitating forces as encroaching fascism, ever-widening income inequality, and technocratic authoritarians, to name just a few.

The series has previously focused on Brockmire’s redemption arc—his journey from the bottom of a bottle to sobriety, from minor-league color commentary to major-league announcing glory, from a washed-up joke to unlikely luminary—against a backdrop of trenchant commentary about baseball and America. In Brockmire’s fourth and final season, all of those ideas gloriously crystallize into a bleak speculative vision of the future. The season takes place in the 2030s, and America has devolved into low-boil apocalyptic chaos. Food and water shortages ravage the nation. Mass riots and gang-related violence are a near-common occurrence. A permanent heat wave has impacted the East Coast. Part of the country has been labeled “the disputed lands,” which basically means they are no longer governed by rule of law. Mutant disease strains have impacted various communities, requiring mass quarantines and the burning of the deceased. (It’s hard to watch Brockmire throw out that last detail and not wince as the coronavirus spreads around the globe.) A sentient Alexa-like device, Limón, has become an inextricable part of daily life, eerily anticipating the needs of civilians and possibly threatening to take over the world. Oh, and baseball is on its last legs: Attendance is in the toilet because of uncomfortable weather conditions and games lasting over five hours. Plus, the league’s superstars are abandoning the sport in droves for other lucrative athletic opportunities, like cricket.

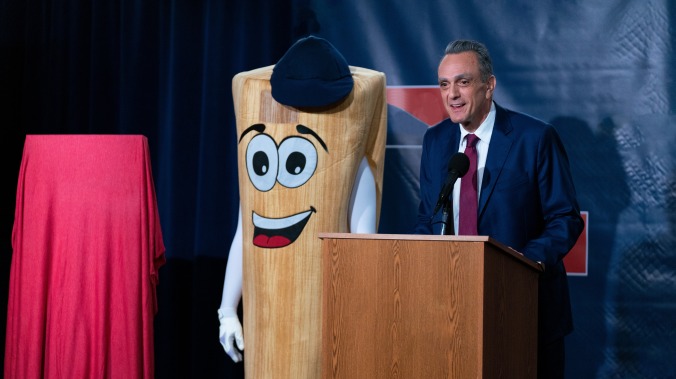

Much like the show’s version of America, Jim Brockmire’s life has also undergone major upheaval. In 2020, Brockmire suddenly finds himself in the care of Beth, a young Filipino girl whom he fathered during his blackout years in Manilla. Beth’s only knowledge of her father is from reruns of Puso Sa Puso, a Filipino knockoff of the ’80s ABC series Hart To Hart starring Brockmire in the Robert Wagner role, and she immediately embraces him upon landing in America, blissfully unaware of the messy realities of his life. Instinctually knowing he must step up to the plate, Brockmire spends the next decade dedicating himself to being an attentive, caring father, and subsequently finds renewed purpose in life outside of baseball. But in 2030, when a college-bound Beth (Reina Hardesty) decides to abandon her public policy aspirations for an NYU film degree, the only way for Brockmire to pay her exorbitant tuition is by accepting the powerless figurehead position of baseball commissioner. As Beth pulls away to live her own life, Brockmire’s new purpose is to save the game he loves from obsolescence and enlists the help of his closest allies: Charles (Tyrel Jackson Williams), who has now become a tech giant, and Jules (Amanda Peet), Brockmire’s former love and professional consultant who has been blacklisted from the league after one of her big promotional stunts goes horribly awry.

On paper, that amount of context and setup reads like it would threaten to overwhelm Brockmire, and, honestly, it does constantly teeter on the brink of being too busy, especially for an eight-episode season. Yet, Church-Cooper and his team of writers keep the ship steady by committing to the theme of dragging obstinate institutions into the future kicking and screaming. Brockmire knows that baseball must evolve in order to survive, which not only means changing the mechanics of the game, but also the entire apparatus around it, like the coterie of amoral billionaire team owners as well as a distrustful players’ union, both of whom are deeply disinterested in any reform. It’s a potent analogy for the uphill battle of progressivism; all meaningful change demands a systemic reframing of the world, an inherently frightening notion to anyone comfortable with the status quo. Through this lens, the backdrop of an apocalyptic America isn’t merely an avenue for dark humor at the expense of our current culture—it’s a harbinger of things to come if we stubbornly refuse to adapt. Truthfully, our world isn’t too far off from becoming the one presented in Brockmire. It’s not entirely farfetched for, say, Brazil to build an amusement park on the remains of the Amazon rainforest, or for companies to offer voluntary at-home euthanasia to relieve the burden of debt.

Related video: Hank Azaria and Amanda Peet on Brockmire, braids, and making baseball better

Brockmire’s final episodes imagine a world in which the old ways have either died or are on their way out, but it doesn’t linger on their legacy. Church-Cooper understands that life always moves forward and that nostalgia for their past inevitably whitewashes discomfiting truths. This broadly manifests in Jim Brockmire’s desire to innovate baseball rather than preserve it in amber, but the idea also trickles down to the characterizations of Beth and Jules. It would have been too easy for the series to paint Beth as a spitting image of her father, but instead she embodies a new path for the Brockmire lineage, one that channels a genetic predisposition for verbosity into other productive directions. Jules, on the other hand, mostly remains the same—the natural salesmanship, the passion for baseball, the casual alcoholism and cocaine use—but her relationship with Brockmire becomes its own tribute to how love can undergo profound transformation as people deepen and change.

Even if Brockmire had never assumed any of these ambitions, let alone followed through on them, it would still be one of the funniest shows on television on a line-by-line, scene-by-scene basis. The one-liners still move at fastball speed, but the show’s sharpened political conscience has only made them land harder. Lots of half-hour shows are praised for their ability to manage and maneuver between different tones, but Brockmire is one of a select few that sports a genuine Frank Capra-esque romantic streak on top of balancing crass comedy with intimate drama. (A character gives an emotional speech late in the season that can only be described as swoon-worthy.) It also remains a phenomenal showcase for Azaria, who, simply put, gives the best performance of his career. It’s downright poetic that an actor known for his iconic voice performances reaches new levels of artistry by a) playing a character who speaks into a microphone for a living, in b) a series that interrogates the very idea of who gets to have a voice and why. It’s telling that we never see Brockmire in the booth this season: He’s using his power for rhetoric to actually impact the game instead of just comment upon it.

It’s neither dramatic nor unreasonable to suggest that we are currently living through unstable times when the future has never been more uncertain. It’s easy nowadays to draw the shades and retreat from the world, just when it needs us the most. Brockmire began its four-year run with its title character doing just that following his public humiliation in the broadcast booth. He withdrew from society to drown his feelings in drugs and drinks, only to return and find his life in the same shambles where he left it. With its last episodes, Brockmire makes a radical pitch right as our reality hurdles toward dystopia: Don’t run away. Find or create communities of loved ones, try to shape the world in any minor way, and cherish the moments of anticipatory calm before the proverbial crack of the bat. Brockmire, the show that started as a throwaway Funny Or Die sketch, fervently argues that life might be short, but there’s still some time. And despite all evidence to the contrary, you’re going to want to see what happens next.