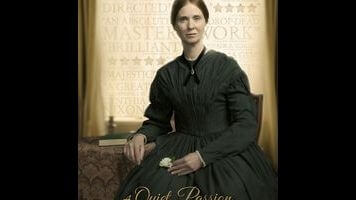

One of the most remarkable moments in A Quiet Passion, Terence Davies’ witty and stirring Emily Dickinson biopic, is a simple transitional device. Emily, played as a teenager by Emma Bell, has sat down to pose for what will become one of the only surviving photos of the poet, taken in 1847. Davies slinks his camera forward, pushing in on her face, until—through some almost imperceptible trick of the light—Bell has transformed, before our very eyes, into Cynthia Nixon. This amazingly seamless special effect serves a practical function: A Quiet Passion has leapt from Dickinson’s youth to her adulthood, and from here Nixon will take over the role. But given the preoccupations of this great American artist, unsung in her own time but almost universally beloved today, the moment shudders with an additional significance. Emily knew, as well as any, that life is short. It can pass in what seems like just a moment, until one day you scarcely recognize your own face in the mirror or photograph.

It would be difficult to make a movie about Emily Dickinson that didn’t take obsession with death as a key theme. Death haunted Dickinson’s thoughts, and especially her work; she found beautiful ways to convey a lifelong anxiety, instilled as early as childhood, when the passing of a second cousin struck her with an incurable case of melancholy. In A Quiet Passion, the “deepening menace” of death creeps around the outer edges of the frame, butting its way into casual conversation and sometimes interrupting the flow of events, as during a quick tally of the Civil War’s inconceivable body count. For Davies, one of Britain’s greatest living filmmakers, such morbidity is nothing new; this is but the latest in a line of sumptuous dramas—The House Of Mirth, The Deep Blue Sea, last year’s undervalued Sunset Song—that find the great beyond closing in on despaired heroines. What’s surprising about A Quiet Passion, given the writer-director’s own incurable melancholy, is how lively, how flat-out funny, it frequently is. The film sometimes flirts, even, with becoming a full-on comedy of manners, at least before characters start keeling over and breathing their last breaths.

So much of A Quiet Passion’s unlikely snap comes from Nixon, in a role-of-a-lifetime performance of great billowing emotion, but also of quicksilver intelligence. Dickinson, as Nixon plays her, isn’t just the smartest person in every tastefully decorated, softly lit room. She’s too smart for her entire era, like a stranded time traveler, wearing the truth goggles of common sense. Together with her sister, Vinnie (Jennifer Ehle, in a rare role worth her warm talent), and an irreverently modern friend, Vryling Buffam (Catherine Bailey), Emily bats guests, suitors, and uptight relatives around like a cat playing with its food—an intellectual game hunt that seems to fill her father (Keith Carradine) with a mixture of disapproval and begrudging pride. (On the Davies spectrum of stern dads, he’s father of the year material.) What fuels Dickinson, and the movie itself, is a love affair with language: Both find joy, refuge, and sometimes a surgical defense mechanism in the manipulation of words.

Like Mr. Turner, another recent artist biopic from a British master, A Quiet Passion builds a vivid 19th-century world around the prickly personality of its subject. Davies has no interest in deifying Dickinson—history has done that job for him. His script, a decade-spanning tour of the key chapters in the poet’s life, recognizes the traits that may have alienated her from the stuffed shirts of Amherst and academia: her disinterest in social mores, her sometimes crippling bitterness, the way she could hone her penetrating wit into a weapon. Without sinking into total pop psychology, A Quiet Passion recognizes a desire for independence as a driving motivation. This applies not just to her rejection of organized religion’s demands (“My soul is my own,” she insists, when pressed by her father and her instructors), but also to her decision never to marry—though Davies, who’s been open about his own lifelong rejection of romance, doesn’t deny the resulting sting of loneliness. (Nor does he depict Dickinson as asexual: One fantasy sequence, in which a gentleman caller climbs the stairs to her room in the dead of night, has an elegantly seductive pulse.)

Davies can’t sidestep the sadder details of this life story. They are, perhaps, part of what drew him to the project. Dickinson became increasingly reclusive in the last few years of her life, retreating to the perpetual solitude of the Massachusetts home where she grew up. Death, disease, and depression blow like a cold draft through A Quiet Passion’s backstretch; even those who didn’t glaze over during the gorgeous, static suffering of Sunset Song may wish this new film’s spritely barrage of bon mots—and Nixon’s radiant delight, dimmed by one too many losses—didn’t give way to strokes and seizures and private anguish. But there’s a defiant power to the image of Nixon-as-Dickinson clothed in all white, rejecting death and even the mourning process itself. Besides which, when it comes to capturing domestic spaces, and the conflicting emotions they house, there’s no one like Davies, who modulates the mood with nothing more than a change in the intensity of daylight streaming in through a window. One’s childhood home can feel like a prison and a sanctuary at once. For Dickinson—stealing herself away from the world, studying it only through the thin crack of her bedroom door—the four walls become an extension of her headspace, where misery and comfort entwine.

The real tragedy of Dickinson’s life isn’t that it ended, as all lives do, but that it began perhaps a little too soon: Her writing was never appreciated in its time, and she died sadly unaware of the posthumous acclaim that awaited her. But if A Quiet Passion doesn’t quite build to a happy ending, it certainly lands on a bittersweet one, a ray of sunshine streaking through the gloom and doom of the poet’s last days, like the light passing through the clouds in the final minutes of Davies’ masterpiece, The Long Day Closes. Throughout the film, Nixon reads Dickinson’s poetry aloud in voice-over, the famous stanzas intersecting, informing, and commenting upon the events that may have inspired them. Davies reserves “Because I Could Not Stop For Death” for the movie’s inevitable conclusion—a no brainer on par with Todd Haynes withholding “Like A Rolling Stone” until the end credits of his biopic. But for all the grim relevance of the poem itself, the words also transform a funeral march into something closer to an ascension. “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” Dickinson once asked a literary critic. Some 130 years after she took that fabled carriage ride into oblivion, her verse is more alive than ever. Immortality really was there, seated next to her the whole time.