A return to Cross River yields absurdist tales of robot slaves, doomed professors, and other godforsaken misfits

In the opening story of Rion Amilcar Scott’s second collection, The World Doesn’t Require You, the literal children of God are having a conversation about prayer. After Jeez bails David out of jail, and after David asks Jeez for money so that he can buy a drum kit, Jeez tells him to pray, and if David prays, Jeez will listen for guidance from their father on whether or not he should give him the money. At church that Sunday, David broaches the topic. “‘God answers all prayers,’ [Jeez] said. ‘Sometimes God’s answer is no.’”

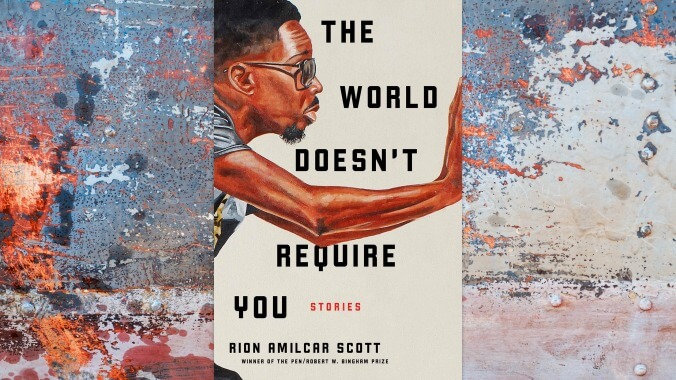

The World Doesn’t Require You feels like a collection about people to whom God said no. In the fictional town of Cross River, Maryland—founded after a slave revolt and where Scott’s first collection, Insurrections, was also set—among the forsaken is a driver for a group of criminals; a public speaker who uses his proclamations of a War on Rape to seduce women; and in the rip-roaring novella that closes the book, a pair of doomed college professors.

One of the worst off is a robot butler, first appearing in “The Electric Joy Of Service,” called “Little Nigger Jim” by his creator, referred to only as the Master. Scott explains the Master’s business plan: “Rich whites will rush out to buy their own robot slaves, the Master said. And we can make these things any race the customer pleases. Little Asian Jims. Little Wetback Jims. Little Cracker Jims. Anything.” The robots are a hit, though not in the way the Master is hoping. His partners are disgusted by his proposal, so they cut him out and produce standard robot helpers instead.

Scott choosing to have Jim narrate the story rather than the Master gives it a kickstart, but the way Jim thinks is what really makes the story hum. His strong awareness of what he can’t have or feel is stirring. Jim and the other robots are so detailed and unique as to resist being read as a more universally recognized metaphor for past or present oppression.

In this way, Scott makes his stories feel singular. He bends expectations throughout the book, frequently demonstrating this idea from the aforementioned public speaker: “Everything horrible is just a little bit ridiculous, and vice versa.” And despite how clear Scott is about this modus operandi, he constantly surprises, pushing things just a little further in either direction. Just as readers have a chance to get their footing, a bird screeches at such a loud volume that eardrums are shattered, and then things get worse from there.

This holds true when Scott stretches his legs. The novella that closes the collection, Special Topics In Loneliness Studies, is a romp about the destruction of an academic’s career. The story begins at the end, with campus police arresting Dr. Reginald S. Chambers in his classroom:

Should we still do the reading from the Hudson book for next class? a student called as the officers escorted Dr. Chambers through the doorway. He wasn’t sure if he should regard the remark as a joke or a moment of idiocy, so he replied, As always, check the syllabus. The woman officer to his right shoved him hard as if to say, Shut the fuck up!

This high level of energy and humor, which Scott maintains throughout, makes the novella a standout. Once Scott circles back to its chronological beginning, the story follows the relationship between Chambers and Dr. Simeon Reece, who lives in the basement of the communications building. The novella is told in a dispassionate third-person until the façade is dropped: “Look, this is all bullshit. How do I know so much about Dr. Reece? Slip the mask. It is I, Dr. Simeon Reece.” A few pages later Reece reveals that his classes aren’t officially offered by the university, though he seems unbothered by this. “When your eyes are truly free you can see the academy for the dystopian wasteland it is,” Reece says. Presumably his financial independence from the institution in which he operates is what allows him that freedom.

Reece develops a trustful rapport with Chambers. Eventually, Chambers admits to Reece that he has backed himself into a corner: In order to cover after being caught watching pornography at work, Chambers tells his boss that he is working on a paper to tie the content of the films to the idea of loneliness (hence the novella’s title). Scott presents Chambers and his project as absurd, while also making the project itself compelling to read. This is exemplary of the balancing act the author pulls off through much of the collection, as his troubled characters try their best to make do with the weight of difficult histories strapped to their backs. Though God may have forsaken them, Scott does not. The World Doesn’t Require You is full of horrible, ridiculous people, but it’s full of grace, too.