A Series Of Unfortunate Events’ commitment to format is saved by a petrified guest star

And now we head into rough seas (sorry, lake), where it becomes even more obvious that, at least in its first few installments, A Series Of Unfortunate Events has a very obvious template. Call it a Misery Lib:

1. The Baudelaires, after finally managing to defeat Count Olaf (who escapes), are sent to live at [visually striking place that could potentially get you killed].

2. There they meet [name of an individual with some ill-defined connection to the Baudelaire parents], who will be their new guardian.

3. Eventually Olaf catches up with them, disguised as [name that Olaf repeatedly forgets], fooling the guardian but not the children.

4. The guardian falls afoul of Olaf’s villainous plans, and it’s up to the children to find some way to defeat him again, without much help from the present but largely useless [Mr. Poe.]

In a way, this should be familiar to anyone who’s watched television for more than a decade or two, because, at least before serialization swept the nation and our hearts, every show had a template. (If not every show, then the vast majority of them.) What makes A Series Of Unfortunate Events trickier is that most shows had more variables to consider. On Columbo, you knew there was going to be a murder, and that you’d follow the murderer around for a bit leading up to the crime before Columbo would show up and start nosing around. But that format left a lot of room to improvise. Here, all that really changes between two-parters is the setting and the guardian. Sure, Olaf’s wearing a different costume, but he’s still Olaf, and he still does more or less the same jokes we’ve come to expect from him by now. (Same with his henchpeople.)

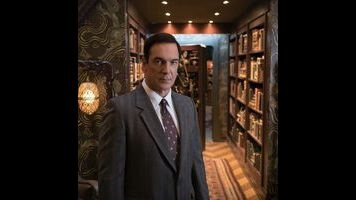

Then there’s the “two-parter” rub, which offers lots of opportunities to stuff in, well, stuff around the edges. In “The Wide Window: Part One,” the main action is at Aunt Josephine’s cracked and dismal house, way up on a very tall cliff overlooking Lake Lachrymose. But in between watching the Baudelaires take the measure of their latest disposable babysitter, we get a couple scenes of Olaf doing shtick, first rowing to shore (well, being rowed), and later, accosting a waiter in town who just happens to be a member of the same secret organization. This last part does some important world-building—namely, letting us know that Snicket (or at least a Snicket) was part of the organization, that he (or she!) is considered extremely good at whatever it is they do, and that Olaf thinks Snicket is dead. But, as with all of the scenes that focus on Olaf, it still feels a bit forced.

Thankfully, the scenes at Aunt Josephine’s house do a great job of holding everything together. This is due in no small part to Alfre Woodard’s wonderful performance as Josephine. I’m not sure Woodard would’ve been the first actress who springs to mind when it comes to playing a character who’s afraid of (nearly) everything, but Woodard is just great; near-hysterical one minute, borderline priggish the next, and yet always with just enough of a real person underneath to make her seem legitimately vulnerable and tragic. She’s a cartoon like most everyone else on the show, but she’s a human cartoon, which makes her interesting.

It doesn’t hurt that Josephine’s relationship with the Baudelaire parents and the secret organization makes a lot more sense than poor Monty’s did. Whereas Monty was apparently still involved in the organization (to the point where he was getting coded messages telling him what to do next), Josephine has put her past behind her. The death of her beloved husband, Ike (devoured by the Lachrymose Leeches), has made her a shell of her former self, unable to move on and too scared to be comfortable staying in one place.

That makes her vulnerability to Olaf less of a narrative convenience, and more a symptom of her inability to deal with her grief. If you squint, you could say Uncle Monty didn’t see his fate coming because he was so blinded by his scientific pursuits that he failed to pay attention to the outside world. But that doesn’t really hold up. And while Olaf’s victims don’t necessarily need to be complicit in their own doom, it works better dramatically (and makes more sense) if the various adults the Baudelaires find themselves saddled with fail in their roles as guardians for reasons more complicated than “Olaf was wearing a funny disguise.”

Not that Aunt Josephine is necessarily doomed; despite all signs to the contrary (a scream, a suicide note, a shattered window with a hole in a suspiciously familiar shape), Lemony Snicket assures us at the end that Josephine isn’t dead. (Then he adds, “Not yet,” because that’s the kind of story this is.) But whatever the precise dimensions of her circumstance, things aren’t going well for her, and the way she fixates on fictional terrors while waltzing into the arms of the realest terror of them all provides a clear moral that gives her situation more weight than mere calamity.

I’m belaboring the point a bit (a phrase which here means “oh god have I written enough words yet to justify my paycheck”), but it’s impressive how much cleaner and more effective this episode is than poor Uncle Monty’s introduction. The writing and Woodard’s work strike a fine mixture of the obtuse and the sympathetic—even Josephine’s pedantic obsession with grammar manages to be sad, albeit in an irritating, nitpicking kind of way. She’s so busy correcting “Captain Sham’s” badly written business cards that she misses, well, everything else.

This is, of course, just the first half of the story. That makes it difficult to judge as a complete work, but on the whole, “The Wide Window: Part One” does a solid job of setting things up for “Part Two,” introducing information that may be important later on (leeches, heights, statues, grammar, “Not yet.”) in ways that feel, if not organic exactly—I’m not sure you could call anything in this story “organic”—at least unobtrusive and clever and acceptably plausible. And for once we get a cliffhanger that is both legitimately suspenseful and involves an actual cliff. The template is wearing a bit thin, and we’ll see how much longer it holds up.

Stray observations

- “For Beatrice—I would much prefer it if you were alive and well.”

- And then there’s that Mother and Father scene, which officially confirms, at the very least, that this is a married couple we’re looking at. Still not sure it’s the Baudelaires’ supposedly deceased parents, but it’s good to have that nailed down.

- Count Olaf and his gang have a curious squeamishness when it comes to killing. Olaf is perfectly happy to murder the hell out of Monty, and either he or one of his own did in poor Gustav. But both Jacquelyn and the waiter at the Anxious Clown survived their encounters.

- There’s a hurricane coming, and the final scene with Lemony shows him standing in the ruins of where Aunt Josephine’s house used to be. There may be a connection.

- “Who knows where he came from?” “You put us in his care.” (I’ve read some criticism of the children’s acting on the show, and admittedly it’s nowhere near as dynamic as the adult performances, but I think it works. Something about the low-key approach makes those moments when Klaus expresses legitimate frustration land really well.)

- “I knew your parents a long time ago, when things were very different.” -Aunt Josephine.

- Some gorgeous direction from Barry Sonnenfeld. I especially liked the shot that went up over Josephine’s house and down the cliff to Snicket in his rowboat.

- The Baudelaires are allergic to peppermints. It’s a small joke, and mostly one made at the expense of Mr. Poe, but it’s a nice, unusual touch, reminiscent of the Baudelaire fondness for beach trips on cloudy days. These are not ordinary children.

- Both Ike and the Baudelaires’ mother could whistle with crackers in their mouths.

- “Plenty of boys enjoy playing with dolls.” -Klaus

- “Who is this Count Omar? He sounds handsome!” -Count Olaf

- We close “The Wide Window” on Monday.