A sharp new book lets ’70s B-movies tell the story of an under-seen America

Given the often years-long development time, movies are not a great barometer for of-the-moment attitudes and zeitgeist-hitting relevance. In hindsight, however, films become time capsules of an era, both for what’s shown onscreen and its relation to what was happening offscreen. Hollywood’s last golden age, the 1970s, has been endlessly mined for what the decade’s great films—everything from Taxi Driver to Jaws—might say about the United States, from its politics to its fashion and back again.

Charles Taylor, in his provocative and engaging new book, has a different target in his sights: He’s after the films on the disreputable end of the spectrum, arguing there’s as much to be gained from studying the best B-movies of the era as there is the classics. “I want to suggest,” he writes, “that the reach of an extraordinary moment in American filmmaking extended to films that were overlooked and made on the cheap.” It doesn’t seem like a terribly controversial argument—who, in this day, would argue that the ’70s didn’t also produce fascinating and rich genre films despite low production values and trashy or salacious content?—but Taylor invests his study with a breadth and scope admirable for its ambition. Taylor’s subject is as much America as the films which reflected it—and his claim is that the movies under his microscope effect the same split between narrative and cultural snapshot. He’s concerned with seeing the broader contours of how art reflects society and the world in which it churns. In the collective experience of seeing these movies in the venues that best housed them, he argues, audiences could feel they were entering “a vision of a troubled and tattered but still vast America.”

Opening Wednesday At A Theater Or Drive-In Near You is never less than a fiercely argued encomium for the socio-historical virtues of the great ’70s B movies, in all their messy beauty. Taylor occasionally veers dangerously close to being a stereotypical grouch about the contemporary state of cinema—a book-length version of “They just don’t make ’em like they used to,” its author a sentient “Why, in my day…” anecdote—but when it comes to his actual subject matter, he’s engrossing and persuasive, pulling off the rare feat of turning cinema into works of cultural anthropology without losing his reader in either long-winded minutiae or overly simplistic summaries. He’s mastered the art of film criticism as historical analysis, using these movies as a way in to the study of an America that no longer exists—and, using his movies to tee off against other, more reductive films, the idea that maybe a happier one never really did.

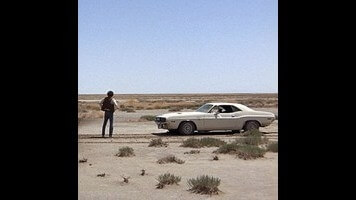

Chapter by chapter, Taylor’s chosen films make the case for a honest and sincere representation of parts of the country that were under-served or unrepresented by the mainstream movies of the day. Scenes, characters, and even entire films that might at first glance be made of little more than clichéd Americana—state fairs, car culture, even blacksploitation tropes—are shown to contain layers, as philosophically rich and artistically authentic as any work of art. That their directors would likely never characterize these films as such is part of what draws Taylor to them, the refusal to claim the cultural high ground an important part of why they traffic in such gritty reflections of the painful and politically charged world that birthed these pictures. Much of his appreciation stems from the artistic flourishes smuggled into what were billed as “exploitation” films, the poetry and thoughtfulness that existed side by side with genre pleasures. “The movie wasn’t what anyone would expect from that description,” he identifies as a strength of Vanishing Point, one of his chosen films, and it’s an integral element to all these movies. They contain something that couldn’t have been predicted, and they challenge their audience’s assumptions and expectations in ways impermissible to big-budget studio projects.

Each film becomes a way in to a world (and worldview) that was rarely shown onscreen, at least with such unfliching honesty. The grimy Lee Marvin/Gene Hackman crime thriller Prime Cut becomes a portrait of “an America rapacious for flesh.” The music-laced noir picture Cisco Pike is an exercise in failed escape, a depiction of the rot that infects places and the people that live there, a rot that even the open road can’t cure. A pair of films by the writer-director Floyd Mutrux, Aloha, Bobby And Rose and American Hot Wax, become bookends to the role of rock music in shaping the identities of young Americans. The former is about the stolen promise of the American dream, a film “about people who feel the pull of nostalgia before life has given them anything to feel nostalgic about”; the latter, a celebration (now elegy) for rock ’n’ roll as a form of democratic pluralism, a tool to lay bare the still-gaping holes in civil society that no melting-pot ideology has been able to fuse together. These films aren’t wholly pessimistic, and they’re not naive, either; they’re searing indictments of easy homilies and folksy moralizing.

Taylor, a lively and passionate critic whose own moralizing has occasionally seen him making more than a few enemies in very public fashion, is in his element here, and the book’s strengths come from the same well of ferocious argument that also powers its weak spots. Those who see odious sexism in Sam Peckinpah’s work are unlikely to be moved by the extremely charitable reading Taylor performs of the director’s uglier moments, even as his chapter on Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia makes a convincing case that Peckinpah’s fans have misunderstood what makes the film so indelible. And it’s certainly possible to remain skeptical of what Taylor loves about some of his selections. His reading of what makes Irvin Kershner’s Eyes Of Laura Mars great is idiosyncratic at best, and those who haven’t seen the movie may come away with a very strange understanding of what it’s actually like.

But that’s part of Taylor’s point: The individual experience of the film can’t be flattened into a one-size-fits-all package, any more than these louche-seeming movies can be lumped into an easily digestible analysis. These films are rebuttals to the political and cultural attempts to reduce the era to its most readily available symbols, the laziest sloganeering, the cheapest iconography. For Taylor, they may be the howls of resistance to a form of cinema he no longer thinks exists, but regardless of his contemporary cynicism, his words evoke a world of cinematic sociology that is transportive in its depiction.

Purchase Opening Wednesday At A Theater Or Drive-In Near You here, which helps support The A.V. Club.