A spoonful of nostalgia helps the calculated Mary Poppins Returns go down

Mary Poppins isn’t a great childcare professional because she’s magic. Her real power is imagination. (Let it be established upfront that a high tolerance for extreme earnestness is a must-have for anyone hoping to make it through two more hours with England’s most airborne nanny.) She does the same thing as any parent worth their salt, and gets rambunctious youngsters engaged in daily drudgeries by refashioning the quotidian as adventure. Make a task into a game, and kids will do whatever’s expected of them. This even works on babies; swallowing a spoonful of orange paste is gross, but helping an airplane land on the runway is fun.

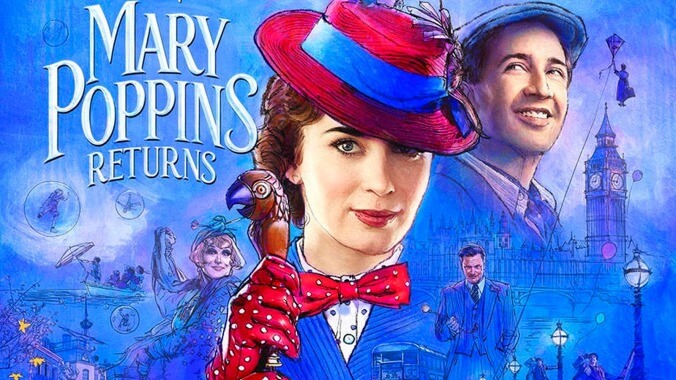

In theory, then, the new Mary Poppins Returns should cast an even more potent spell, what with all the advances of modernity at its disposal. And indeed, the zippy musical numbers in which Mary Poppins (a stiff-lipped Emily Blunt) whisks cherubs Annabel, John, and Georgie (Pixie Davies, Nathanael Saleh, and Joel Dawson, respectively) away into colorful hyperreal fantasias impress. But they often impress in the same remote, impersonal manner as the floating chunks of island from Avatar—mighty in form, lacking in soul. They inspire more respect than love, and Mary Poppins is nothing without love.

Moments of potential transcendence, such as an afternoon constitutional through an expressionistic wonderland recalling the Fuji Velvia vividness of What Dreams May Come, ring false in light of this project’s mercenary origins. Director Rob Marshall and writer David Magee repeatedly wink toward a presumed awareness of the 1964 original, all the while doing everything in their power to convince us that this film comes from a place of sincerity and not a tall stack of intellectual property contracts. It’s the Poppins we know and love, back to restore our dimming sense of childlike amazement—on behalf of a gargantuan, sinister corporation currently waging a campaign to mechanically extract every available dollar from our earliest memories. This paradox plagues all of Disney’s output, but Mary Poppins Returns’ vocal emphasis on the beauty of nostalgia foregrounds that tension. It’s less heartwarming than heart-microwaving.

How apropos that Mary Poppins should decide to revisit the Banks family just when they’ve become hard up for cash. Now adults during the economic “Great Slump” of the ’30s, siblings Michael (a mustachioed Ben Whishaw) and Jane (Emily Mortimer) are in danger of losing their beloved family home due to some delinquent loan payments. He’s down in the dumps because nobody wants to buy his art and his wife died, while she’s got a case of the gloomies in response to public apathy for the plight of the underclass. Their grown-up troubles form an odd angle with the purportedly innocent feel-goodery, and ultimately betray the film’s cross purposes. Whenever Marshall starts to work the old-fashioned charms as intended, he invariably does something calculated to widen appeal for a broader, modern viewership. Sometimes it’s a conspicuous genuflection to the adults who must be reassured that, yes, this is for you. Sometimes, it’s in the weird anachronisms, like a sudden bit of freestyle BMX choreography or a speed-rapped verse from a severely misplaced Lin-Manuel Miranda (doing a heinous Cockney brogue as an ostensible allusion to Dick Van Dyke’s famously bad accent work in the earlier film).

Every effort to update or refresh that actually succeeds then ends up contaminated by a reminder of the film’s overeagerness to sell itself. Blunt, for one, knows exactly what she’s doing. She glides through her scenes even when she’s not literally aloft, offsetting her sterner side with prim but genuine affection in her dialogue, then grinning her way through the energetic toe-tappers. Like the technically astounding and spiritually hollow production numbers, however, Blunt can’t situate the sentimental energy in a deeper foundation. Her excellence gets left in a sort of vacuum when paired with the fully extraneous train wreck of a visit with Meryl Streep as kooky Poppins cousin Topsy or some discomfiting soft shoe from a creaky Dick Van Dyke.

There’s a scene near the end in which our ensemble receives some wholesome wisdom from a woman selling balloons in the park, portrayed by Angela Lansbury. Her presence and the momentousness appended to it make no sense, because this role was very clearly conceived for Julie Andrews, who wanted no part in all this. Perhaps this section could have been easily edited out of a run time cracking the two-hour mark, but Marshall is more concerned with recalling a great film than making one. Technology can enable Hollywood to whip up a cabaret full of bustling, chattering animals or a kaleidoscopic undersea jaunt, but feeling cannot be added in post.