A veteran considers an Afghan soldier’s perspective on war in Green On Blue

The title of Elliot Ackerman’s Green On Blue refers to acts of violence by “green” Afghan soldiers against “blue” U.S. troops, but it’s the unending stream of “green on green” offenses that are the real focus of this debut novel, a thin but well-intended attempt by an American veteran to wrestle with the impact his country had on the country it went to war with.

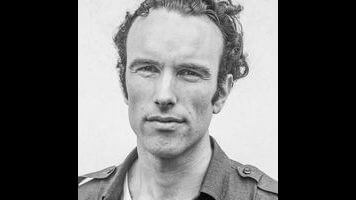

Ackerman served five tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, and part of his deployment included time embedded with Afghan tribal armies. (The book is dedicated to a pair of Afghan soldiers he befriended, Aziz and Ali, the namesakes of brothers in the book, though it is not otherwise based on fact.) It’s that experience that informs the bulk of Green On Blue, which tracks an orphan who joins a “Special Lashkar,” a militia funded and supported by the United States.

If only to bring greater awareness of these groups, along with other unconventional measures and allies the U.S. military took on throughout the course of its longest-ever war, the book has value. But its “first novel” qualities are readily apparent. Ackerman has some strong instincts, including an ending that is very bold given his background, but those instincts do not have an equal in his prose.

In the book’s press notes, Ackerman is quoted as saying that early drafts featured a prominent American character that he later cut, feeling him “a crutch I’d built because I’d yet to find the courage to allow the novel to fail or succeed on the strength of Aziz’s voice.” It’s a noble impulse—he is very ambivalent about American motives—but confident is one thing Aziz’s voice is not. Ackerman writes as though he’s worried he’s going to offend or break something.

Here is Aziz after learning his parents have died: “I clutched my hand to my chest. It strung from where Ali had struck me. I opened my mouth to speak, but my throat filled with the sorrow of all I’d lost. I swallowed, then asked: Where will we go?” (Ackerman’s decision to forgo quotation marks for dialogue makes for unnecessary paragraph-to-paragraph distractions when his characters launch into speeches, and even when the speaker is clear, the absence of this punctuation visually adds to the perception that the book is unstructured.)

It’s clear this is meant to be sparse and poetic, but it comes off as thin and rushed, to the point where major events carry no impact at all. After their parents’ death, Aziz and Ali spend years as street urchins until Ali earns enough money for Aziz to attend a madrassa, an education that is cut short when Ali is injured in a bombing, leading Aziz to join the militia to seek revenge and provide for his brother’s medical care.

That whirlwind all occurs in the first 30 pages of the book, and covering that much material in so short a section means depth has to be sacrificed (the excerpt above is the entirety of Aziz’s mourning). There’s no sense of place or local color, no insight into how the brothers feel about their hard-knock life. Whole personalities are reduced to lines of pseudo-philosophical dialogue (“I ask no man to trust me and I trust no one. Trust is a burden one puts on another,” says a shopkeeper they briefly work for), and the first chapter feels like it should be the first third of the book, so we can feel the weight of that world being violated.

While more time is spent on Aziz in the Lashkar, that too is more sketched out than probing. Outside some very on-the-nose lines that do not sound like the musing of an adolescent (“Had I become the very thing I despised, that which I wished to destroy?”), Aziz’s growing political consciousness and moral dilemmas are woefully underdeveloped. The book as a whole lacks the kind of insight you would expect from someone who was this close to his source material. He notes that three-seated military vans are known colloquially as an “asses-three” because the Red Army designation for them was AS-3. That this fact is included while emotional details are skimmed over suggests Ackerman was reluctant to give himself the dramatic license of fiction to expand on what he observed and actually speak for his characters.

Ackerman has written eloquently about his military experiences in The New Yorker, which suggests it’s his newness with fiction that has stymied him here. There may not be much precedent for an author to do what Hitchcock did and remake his own work, but it’s easy to imagine Green On Blue, were Ackerman to revisit this material with new confidence, expressing the power of its subject in all its moral complexity.