A War is almost too measured in its treatment of military protocol

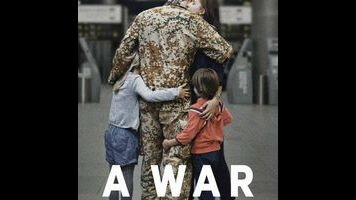

One of the four films destined to lose the foreign-language Oscar to Son Of Saul, Denmark’s A War sees writer-director Tobias Lindholm (A Hijacking) once again juxtaposing a simple title with a complex situation. The war in question is the one in Afghanistan, to which Denmark sent 9,500 soldiers between 2002 and 2013. Claus Michael Pedersen (Pilou Asbæk, who also starred in A Hijacking) commands a unit that spends most of its time protecting innocent Afghan civilians from Taliban attacks. The film spends much of its first half-hour or so establishing Claus as a thoroughly decent guy who’s genuinely concerned about the men he sends out on sometimes lethal patrols; when one of them experiences post-traumatic stress after seeing a friend blown apart from by an IED, Claus gives him pencil-pushing duties for a while, and later even accompanies him in the field. However, that means that Claus happens to be with the company when it’s suddenly ambushed, and winds up making a decision that saves his men’s lives at the expense of 11 civilians, including six children. Was he justified? That decision is left to the viewer.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)