A Way Out’s prison-break story shanks itself before it can even make it out of the yard

The best thing you can say about the cooperative nature of Hazelight Studios’ new digital revenge thriller, A Way Out, is that it ensures you’ll always have someone else there to help you cope. A game so beholden to its jailbird movie roots that it shamelessly and haphazardly lifts scenes from The Shawshank Redemption, Scarface, and a dozen other classics of tough-guy crime cinema, A Way Out manages to squander the riveting potential of its co-op premise at almost every juncture, leaving behind only a few weak spasms of brilliance and the mild camaraderie of knowing you’re not suffering through its missteps alone.

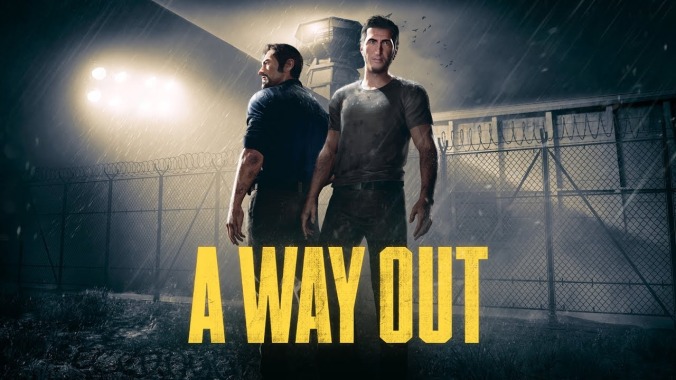

The brainchild of writer-director Josef Fares—whose first game, Brothers: A Tale Of Two Sons, was a far more successful meditation on the nature of cooperation and support—A Way Out centers on two convicts looking to head out on the lam: career criminal Leo and uptight former banker Vincent. Each of the two required players, connected either over the internet or seated next to each other on the couch (ideal for maximum mockery of the game’s Tarantino-as-translated-from-Swedish script), controls one of the two men throughout the game, presented with a dynamic split screen capable of shifting and pulling focus depending on which would-be fugitive is doing the more interesting bit of breaking out at any given moment. As with most of A Way Out’s better ideas, the game occasionally manages to make the most of this cinematic conceit, such as during a late-game sequence that ratchets up the tension by splicing in a window showing a hitman breaking into the room Leo and Vincent are both desperately trying to escape, but for the most part, it’s not a whole lot more impressive than the split-screen tech you might see in a recent Lego Star Wars title.

That “A for idea, C- for execution” feeling is all over A Way Out, which manages to feel barely competent at the many game genres it attempts, whether its asking you and your partner to handle stealth, driving, third-person shooting, or more. These moments—often rife with an unwelcome abundance of that old “cinematic” bugbear, the inescapable quick-time event—are at their best when they force the players to communicate with each other, as in a tricky climbing section where one player moving too quickly can be just as disastrous as the other one moving too slowly. More often, the game simply feels like a clunkier, less-flashy take on Uncharted, propelling the players through a direct-to-DVD Nicolas Cage flick instead of a high-budget Spielberg action-adventure.

The real problem with this low-budget cinematic approach, though, is the way it ruthlessly hacks away at the game’s sense of stakes. Promo materials for A Way Out emphasized the importance of player choice, but in execution, it’s close to nil. Rather than investigating the prison, building up connections, and putting together a plan, players are simply tossed into a series of linear vignettes, all taken from a pre-assembled blueprint. Succeed—by stealing a needed tool or talking your way past a guard, for example—and the plot progresses. Fail, and there’s no rising tension, no rapidly escalating series of consequences or branching outcomes—just some gunshots, a loading screen, and an exhortation to try it again. The violent beauty of a prison break movie is in watching desperate people do dangerous things with absolutely no margin for error. It’s a lot less riveting when there’s a restart checkpoint waiting to let you try again every time Leo or Vincent fuck up.

Speaking of our two heroes, Fares’ script does its damndest to make them feel vital, real, and distinct, but it struggles to ever get the player invested in their eventual fates. (A poorly judged in media res story structure, showing the duo already out of prison by the time the game starts, does it no favors in that regard.) For a game that’s ostensibly about a bond of trust between two guys who are, on paper, very different men, A Way Out does a poor job of distinguishing between its heroes. Vincent (goatee) is a little quieter, while Leo (sideburns) is a little more violent, attitudes reflected in the rare moments when the game asks you to choose between their proposed approaches to problem-solving, but it’s still harder than it should be to tell them apart.

All that being said, the game’s best moments come when it’s willing to calm down its relentless forward motion and just let the two men breathe. Whether they’re exploring a deserted farmhouse, wandering a rural neighborhood, or taking a break to play Connect Four in a hospital waiting room, these quieter moments are when the game makes its hardest sell for your all-important empathy. In one memorable sequence, the two come across a piano and a banjo, each with an option to let one of the two men play it. What starts as a pair of competitive rhythm games, quickly evolves into a shared concert, a brief window into these guys’ humanity amid far too much running and gunning. More of that—and less shooting down gangsters or choking out cops by the dozen—would have helped the game land the heavier emotional beats that arrive when, five-sixths of the way through its tired retreads of Andy Dufresne’s greatest hits, A Way Out finally transitions into its inventive, legitimately electrifying finale.

It’s always difficult, when evaluating a cooperative game, to determine how much of the enjoyment comes from the game itself and how much comes from the inherent pleasures of mutual play. Throughout its runtime, A Way Out is fun, in the way any game with a friend is fun (and that’s definitely the correct way to play it, since playing with strangers would make its communication-based challenges a goddamned nightmare). But outside a few promising flourishes, it ultimately fails to distinguish itself from any number of more engaging co-op offerings, and its best moments hinge on caring about characters who never rise very far above the level of flat, unengaging caricature. There are the seeds for a legitimately great cooperative game buried deep within its cookie-cutter plotting, adequate action, and of course a whole lot of instances when one character has to hoist the other up over a cliff. Players willing to hang on through its ending are in for a couple of unexpected narrative treats, too. It’s just a shame that it takes so long for those early promises to finally bear fruit.