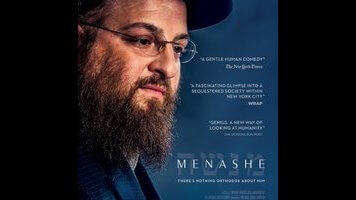

A widowed Hasidic father faces a custody battle in the New York drama Menashe

Before making the film Menashe, documentarian Joshua Weinstein donned a yarmulke and explored Brooklyn’s Borough Park, getting to know the stories and personalities of New York’s Hasidic Jews. That was the easy part of the process. It was trickier when Weinstein returned to the neighborhood with a camera crew to work with the locals he’d hired for his cast. In this insular society—which for the most part has kept itself purposefully cut off from popular culture—the whole Menashe project seemed morally suspect. Weinstein reportedly lost locations and actors as the shoot went on, and left some people’s names out of the credits so that they wouldn’t bring shame to their families.

Throughout, the movie’s key collaborator remained steadfast. And thank goodness he did. Menashe Lustig brings warmth and a lumpen charisma to Menashe’s lead role, giving life to a film based in part on his own experiences. Lustig too is a widowed father from a deeply religious community, where everyone minds everyone else’s business. In the fictionalized version of his life (written by the non-Yiddish-speaking Weinstein with help from Alex Lipschultz and Musa Syeed), he finds himself fighting for custody of his son Rieven (Ruben Niborski), who lives part time with Menashe’s brother-in-law Eizik (Yoel Weisshaus). While the dad works as a clerk in a grocery store, his late wife’s brother is a well-to-do real estate broker, who agrees with their rabbi’s judgment that Menasce needs to remarry and give Rieven a mother before the boy can come home to stay.

Weinstein has said he was drawn to Lustig in part because of his story, and in part because the amateur actor had already shown a willingness to skirt the customs of his culture, by posting comic videos on YouTube. Much of Menashe’s tension springs from how the title character genuinely desires to be devout, while also wishing he lived somewhere where he was allowed to loosen up a little. Menashe is playful by nature, which serves him well at times. He’s helpful to customers in the grocery and is the kind of father who’d rather go get ice cream with his son than nag him to do his homework. He also clearly loves a lot about his faith, like the sense of fellowship and the sincere efforts to understand and explain the deeper meaning of life.

But when he’s too nice on the job, his manager complains that he’s putting the customers ahead of profits. When he has fun with Rieven, Eizik complains that he’s irresponsible. When he attends religious functions, he hears gripes from his fellow Hasidim that he drinks too much wine, dances too freely, and offers laymen’s interpretations of the Torah that are well-meaning but unscholarly. Everyone can see he has a big heart, but he’s a bit too unorthodox for the Orthodox.

It would’ve been easy for Weinstein to make Menashe into a melodrama about heroes and villains: the misunderstood free spirit versus the stodgy pillars of the community. Instead, the model here is more the classics of docu-realism, like Little Fugitive, or anything by the Dardenne brothers. The focus is largely on the fascinating and strikingly filmed visual contrasts of an old-fashioned people against a modern city. And aside from the custody issue, the story’s stakes are relatively low.

The slim plot mainly involves Menashe’s attempt to impress his brother-in-law and their rabbi by hosting a successful memorial dinner for his late wife, the preparations for which detour into a brief subplot about a pricey shipment of gefilte fish. Weinstein focuses primarily on his protagonist’s smallest challenges—like whether or not he can prepare an edible dish of kugel for his guests—and is generous enough with every character that the audience can understand why Eizik and others would find Menashe exasperating.

The director also pours as much of his research as he can into every scene—perhaps to an excessive degree. Anyone who knows nothing about Hasidism will come away understanding quite a bit about some of the rules and beliefs that govern Menashe’s life, from the ritual hand washing to the certainty that strict order is superior to the gentiles’ “broken society.” Weinstein includes small details, like the 24-hour candles and portraits of famous rabbis intended to make a memorial dinner more proper, and he explores wrinkles that are far more significant, like Menashe’s insistence that he doesn’t really need a second wife because Talmudic law would prohibit her from ever touching Rieven anyway. Sometimes the dialogue sounds like it was written by that staple of old Broadway mystery plays: “Moishe The Explainer.”

What keeps Menashe from just being outside-in ethnography is how much nuance Weinstein and Lustig bring to the main character. In one of the few scenes in the film in English, Menashe is drinking malt liquor on the grocery’s dock alongside a couple of his Latino co-workers, and he admits that while he desperately loves his son, he never liked his late wife that much. The moment is presented not as miserablism—or as some kind of critique of arranged marriages—but as a matter-of-fact declaration by a guy who leads two lives. Menashe is open enough to respect both of this man’s identities: the child of God, and the ordinary New York schmo.