“A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home,” the journalist and civil rights pioneer Ida B. Wells wrote in 1892, three-quarters of a century before the nascent Black Panther Party For Self-Defense asserted its Second Amendment right to bear arms. Sickened by the number of Jim Crow-era lynchings she had investigated, Wells reasoned that “when the white man who is always the aggressor… runs as great a risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life.”

It will come as news to no one that we are a nation overflowing with firearms, totaling over 310 million, at best guesstimation, nearly one for every adult, teenager, and gun-toting toddler. We don’t just love guns, we are resolutely trigger-happy. Thirty people are murdered each day in the United States by firearms. Half of those victims, on average, are African-American. Yet, only 32 percent of the nation’s black households own a gun, compared with 49 percent of white homes. Well over a century after Wells’ call to arms, it has become increasingly clear: America doesn’t just have a gun problem; it has a racist gun problem.

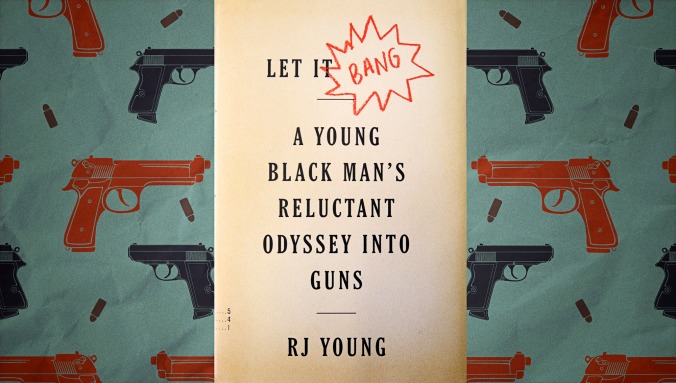

In the humorous and heartbreaking Let It Bang: A Young Black Man’s Reluctant Odyssey Into Guns, RJ Young traces the rise and fall of his obsession with firearms, beginning with a scene straight out of Get Out: An interracial couple is introduced. She (white) brings him (black) home to meet her (very white) family. We cringe at her father’s clumsy attempts to bond with his daughter’s boyfriend. But instead of proving his political wokeness, Young’s future father-in-law brandishes the “biggest goddamn revolver” he’d ever seen. “It was truly a display of friendship,” he writes, unconvincingly.

Endeavoring to understand his new, gun-loving family, while simultaneously horrified by the countless murders of African-Americans by police and private citizens, Young decides to arm himself. Baptism-by-fire-style, his father-in-law escorts him to Wanenmacher’s Tulsa Arms Show—billed as “the World’s Largest Selection of antique, collector and modern firearms, knives, and accessories”—where 40,000 enthusiasts show up to buy guns, sell guns, trade guns, ogle guns, and exalt in the godly glory of gun ownership with the same dedication the innumerable Children of Abraham reserve for Jerusalem. Safe to say, Young doesn’t need both hands to count the number of black attendees.

Young returns home with a Glock 17, a 9mm semi-automatic pistol referred to as “the Honda Civics of handguns.” He becomes a regular at his local shooting range, where white men spit at his feet and ask him why he isn’t shooting hoops or holding his pistol sideways. Frustrated with his marksmanship, he promises himself to become “so diabolically methodical… so fiercely fantastic, that I could inspire in others the fear that they inspired in me, simply by murdering paper targets.” He does just that, becoming a crack shot, earning his concealed-carry permit, and becoming a certified NRA pistol instructor.

Constitutional originalists will forever claim the self-defense doctrine, but after witnessing Young squeeze off round after round after round (not to mention compulsively cleaning his Glock three times a day, like a pubescent boy discovering his own dick), it becomes immediately clear why one firearm isn’t enough for most gun owners. No matter how much heat they’re packing, men will forever feel inadequately armed. Young knows this, repeatedly reminding himself that the weapons he owns serve a single purpose: to kill.

Let It Bang ends with a pair of plot twists. One, concerning his mother, the rare black woman who is a Trump nut and an NRA lifer, comes as a whiplash revelation that deserves a more central place in the narrative. The second is a poignant illustration of the racialized fearmongering that isn’t new to Trump’s America but sure feels intensified over the past several years. Young’s reluctant odyssey educates him on masculinity, race relations, and the “insanity of American gun culture.” But above all else, he writes, his journey into the nation’s gun mania “has made me more afraid for my life than ever before.”