It’s not uncommon nowadays to see a pleasant, very professional, mildly engaging documentary that could just as easily have been a 5,000- to 10,000-word magazine article, saving all involved the trouble of financing and making a movie. Abacus: Small Enough To Jail, which relates the interesting enough story of the only bank to be charged with fraud in the wake of the late 2000s subprime mortgage crisis, is one of these—an unusually literal example, as its major points were previously covered in “The Accused,” an article published in The New Yorker in 2015. (It’s about 6,400 words long.) At its center is the Manhattan-based Abacus Federal Savings Bank, a tiny, family-run institution that caters to Chinese immigrants. In 2012, it was indicted on charges of conspiring to sell fraudulent mortgages to Fannie Mae, despite some very dubious evidence and the fact that the bank boasted an extremely low mortgage delinquency rate. It’s obvious what attracted Steve James, the documentarian behind such films as Hoop Dreams and The Interrupters, to the subject: It was a case of the little guy going up against the big guy that offered a glimpse of the cynicism of prosecutorial discretion.

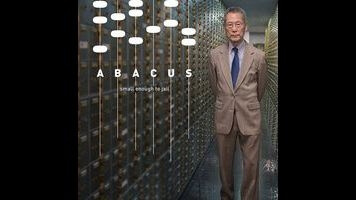

Working in broad strokes that include extensive references to and clips from It’s A Wonderful Life (a point of comparison that one could easily imagine Errol Morris using ironically), James presents Tom Sung, the former lawyer and real-estate investor who founded Abacus, as a deeply committed local businessman who worked hard to earn the trust of his community—a business model that provides the film with its one memorable image, of Sung strolling proudly through the endless rows of safe deposit boxes housed in his modest Chinatown bank, rented to thousands of recent immigrants who needed a place to store valuables while living in tight quarters. Small Enough To Jail is as capable a piece of work as one would expect from James, juggling footage of the Sung family at home, at work, on conference calls, and on the streets of Chinatown; news reports; talking-head interviews; and voice-over reenactments of the Abacus trial (not exactly “trial of the century” material), illustrated with courtroom sketches and interviews with a couple of the jurors. But James’ essentially humanist mode of documentary filmmaking can’t cut through the surface of the surface. Perhaps the problem is that he isn’t one to extrapolate, interrogate, or pry subjects open; his best films are chronicles of hopes, dreams, and hardships made possible by the trust James works to elicit from his subjects.

In that sense, one suspects that he also identifies with Tom Sung as an artist—a keeper honored by secrets. But none of the more dramatic events covered in Small Enough To Jail happened within view of the filmmaker’s camera, and unlike in Life Itself, his very affectionate documentary on the life of Roger Ebert, James doesn’t have the benefit of colorful stories and personalities. The interviewees are repeating arguments that they’ve spent years preparing or making. Many of them are lawyers (including several members of the Sung family), and one, the former chief credit officer of Abacus, even has his attorney with him on camera the whole time. The film stalls at the facts: a niche bank caught in a slightly surreal media circus and trial, where office seating charts and the testimony of an employee who was fired and reported for fraud are brought as evidence of guilt; an unflappable immigrant who came from Shanghai in his teens, made a fortune, and raised four hardworking daughters, each more than qualified to succeed him; a tightly knit community.

As for what all of this represents, Small Enough To Jail doesn’t draw any conclusions that its many interviewees aren’t willing to voice themselves. (The title’s play on “too big to fail” comes directly from one of Abacus’ lawyers.) It’s A Wonderful Life isn’t the only classic movie to be referenced here. As one interviewee quotes, with only a hint of sarcasm, “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.